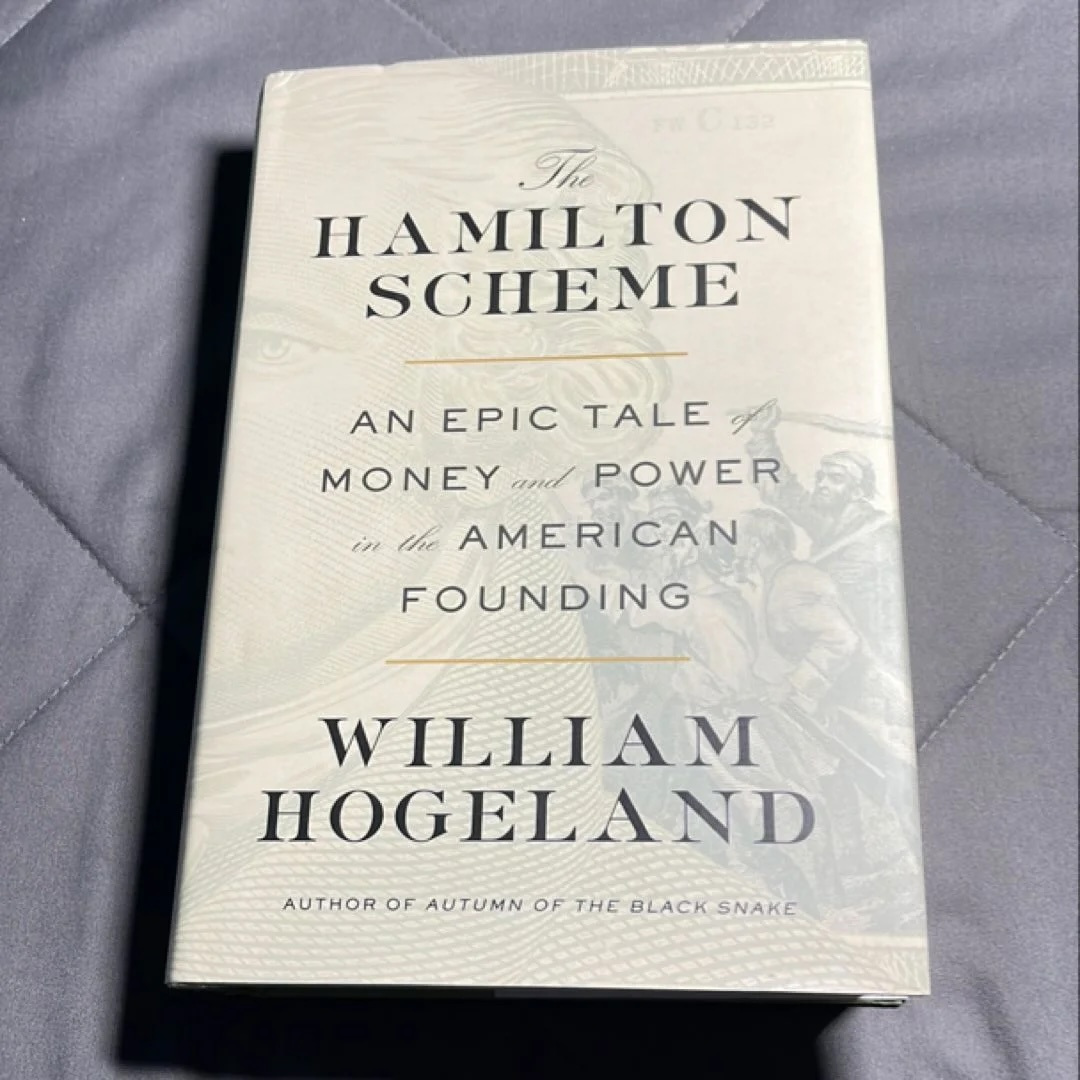

A new book, The Hamilton Scheme, explores a very different founder than the one we’ve come to think we know.

Labor Day is an excellent time to talk about Alexander Hamilton. Because for the last decade, everyone has been talking about Hamilton – in ways that would’ve likely made him scoff.

Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit play, inspired by Ron Chernow’s biography of the subject, painted Hamilton as a daring genius embodying the American Dream and setting the bar for upward mobility – a dashing figure of rivalries, affairs, and death by duel. But that’s just the glossy front; it skips over Hamilton’s darker legacy – especially regarding the aspirations of ordinary people.

Historian Billy G. Smith observes that if he had seen the play, Hamilton would have loathed the “sight of himself singing, dancing, and intermingling on a stage with so many common, ordinary people.” The nobody from Nevis might’ve come from humble beginnings, but once he made it big, he left all that behind for good. The common people? Not his scene.

True, Hamilton was the mastermind behind America’s early economic engine, molding the nation with his big financial ideas and a dream of a centralized powerhouse. But while he was busy crafting a stable financial system and forging a path to national greatness, his policies left everyday workers paying the price.

In his new book The Hamilton Scheme, William Hogeland points out that the founding era is often framed as a Hamilton vs. Jefferson showdown, with Hamilton championing a powerful central government and a robust financial system, while Jefferson pushed for states’ rights and agrarian values — their rift deepened by conflicting views on slavery. But Hogeland’s readers are introduced to a third force in the picture – one that complicates this oversimplified view. That force is none other than democracy itself—the will of ordinary people. People who felt that neither Hamilton nor Jefferson had their backs. (Hogeland further notes that the Hamilton/Jefferson divide over slavery is murky, too, as new research exposes Hamilton’s own connections to the institution).

The affluent craft the narratives, rarely acknowledging the enslaved people who powered colonial prosperity (20% of the population in the founding era) or the white working class, from subsistence farmers and seamen to emerging factory workers (mostly women and children). Yet these people were in the thick of the action, and time after time, they found ways to make it clear that the moves and motivations of America’s founders – especially Hamilton — didn’t look so great from where they stood.

If you peer beyond received narratives, you may find, as Hogeland puts it, that “the Hamilton and Jefferson groups, so deafening in mutual vituperation, collapse into a small hegemony forever bickering over how best to exploit the free majority, as well as the enslaved, and control and distribute the fruits of labor.”

Not a pretty picture.

In a nutshell, we need to talk about Hamilton because while he rose from nearly nothing to become one of America’s key architects, his blueprint for the country created barriers for others trying to climb the same ladder. In fact, he had no problem kicking the ladder away.

Hamilton’s Revolution: the Rich Win, the Rest Lose

When the War of Independence kicked off, colonial elites were railing against British interference in commerce, but as Hogeland makes clear, many tenants and poorer folks were so suspicious of their agendas that they figured sticking with the British might be a better deal than siding with their American landlords.

They had reason to worry. The war operation was being orchestrated by profiteers like Robert Morris, a wildly rich financier who would use his money and connections to mold the new nation’s economy with an eye on making sure his wealth and interests flourished in the turmoil. For him, national greatness meant amassing piles of money through government and consolidating power among the wealthy. Hogeland points out that Morris was among the first to chase the potential of what he termed the “Money Connection” – the art of growing wealth through government.

Hamilton, meanwhile, got rolling during the war as General George Washington’s aide-de-camp, distinguishing himself as a crack administrator. Washington, at that time, was a Virginia land speculator used to rubbing shoulders with greedy financial moguls like Morris and rich landlords like the ruthless Phillip Schuyler. The General was not too thrilled with having to deal with what he called the “exceedingly dirty and nasty people” he was tasked with commanding. Prior to the war, Washington had spent years scooping up huge tracts of western land, building up his grand Mount Vernon estate, buying slaves to carry out his growing experiments, and enjoying copious amounts of Madeira wine and oysters. Hailing from a family of middling means, Washington hit the jackpot by marrying the fabulously wealthy widow Martha Custis and sliding into high society’s upper crust. He’d grown accustomed to the best: his personal expense account during the war included large outlays for table linen, curtains, and eye-popping quantities of wine.

Hamilton, having climbed into the elite himself by marrying Schuyler’s daughter, saw himself, as Washington’s aide, as part of the educated elite charged with keeping the rabble—aka “democracy”—in line.

The studious Hamilton did a deep dive into the British banking system and devoured the writings of European economists and financial officials, turning their complexities into what he imagined as a playbook for American finance. He paid special attention to British Prime Minister Robert Walpole’s use of Crown borrowing to finance wars and imperial projects and took inspiration from Swiss banker Jacques Necker’s vision of the heroic finance minister as the government’s most crucial figure. Hamilton could picture himself as that person – the man through whom all the money would flow.

Beginning in 1779 and hitting full throttle in September 1780 with Washington in New Jersey, young Hamilton cranked out a sweeping plan to yank control of trade, war, and finance away from the states and hand it all to Congress, envisioning a national powerhouse to drive commercial success. Nobody was yet eager to take up his plans, but come 1781, rampant inflation and financial chaos prompted Congress to create the Superintendent of Finance role, with Robert Morris taking on the job. Excited by the financier’s appointment, Hamilton outlined a plan for a national bank as a way to standardize American currency and cope with national war debt and sent it to Morris. Morris, recognizing a kindred spirit – he’d been working on a bank plan of his own – became Hamilton’s mentor, and would eventually bring him on to serve as his receiver of the Congress’s revenue in New York.

Victory at Yorktown may have been a turning point in the war, effectively ending military operations, but the huge financial drain continued with the army’s relentless needs and various post-war federal projects. Congress, lacking its own taxing power, stayed shackled to hit-or-miss state contributions, making Morris’s attempts to fix the broken requisition system glaringly inadequate. Morris had already created the Bank of North America, but it wasn’t enough – it lacked the financial engine that drove the Bank of England. So Hamilton started piecing together the public debt of the United States to rev up the financial system and build a new nation.

The idea was to bankroll the country by issuing government bonds with fat returns – the kind that would line the pockets of the rich and make sure they had a vested interest in propping up the new government. This move left ordinary people at a severe disadvantage, as Hamilton’s financial policies stacked the deck in favor of the wealthy, resulting in lower returns and greater risks for smaller investors who were stuck with worse terms and a devalued portfolio.

The debt, Hogeland stresses, wasn’t some beast Hamilton had to wrestle down, as often portrayed. It was, for him, a marvelous tool for establishing “great concentrations of monetary, industrial, and military power for the purpose of launching an American empire.” It was a means of establishing great credit by paying a very small number of people hefty regular interest payments – right on the backs of everyone else who would be forced to cough up taxes to fund those payments.

The plan socked it hard to those without connections and resources. Small-time veterans and farmers, promised decent returns on their bonds, were left out in the cold as Hamilton’s debt policies inflated elite holdings while devaluing theirs. War widows counting on bonds for stability watched their financial lifeline vanish. The truth was that Hamilton’s plan turned the financial tables in favor of the rich, while the average bondholder was left to pick up the pieces.

As a new country was born, America’s elites may have clashed – some wanting state sovereignty, others federal power, but Hogeland asserts that they could all agree on one thing: “a firm belief that their struggle for freedom from British tyranny was not to be confused with a struggle for political participation by the unpropertied and legislation for the benefit of labor.”

Outside elite circles, a lot of folks dreamed of using the government to achieve economic equality. They saw the Revolution not just as a fight for independence but as a chance for real economic and social change, where regular people could have a say in their own governance. But they were constantly outplayed by those who wanted to protect their wealth, set up a stable government, and make sure they stayed in charge.

Hamilton had no trouble picking a side. To him, democracy was mob rule and must be avoided at all costs. He had little time for radicals like Thomas Paine, who had succeeded in getting a democratic government in Pennsylvania, and he was thoroughly repulsed by prominent agitator Herman Husband, who fired up democratic fervor by organizing and mobilizing rural farmers and working-class people against unfair tax policies, advocating for their rights and a fairer system.

Ordinary people caught wind of the fact that the war they’d been asked to fight wasn’t for their benefit. They saw the debt being used against the very laboring families who had sacrificed for the victory. And they were prepared to take action.

Shays’ Rebellion, a 1786-87 uprising by struggling Massachusetts farmers against harsh taxes to be used to pay wealthy bondholders, was crushed by a state militia under Governor James Bowdoin, with the Society of the Cincinnati—elite Revolutionary War veterans—playing a key role in rallying the militia. Formed to protect the financial interests of its wealthy members, the Society aligned perfectly with Hamilton’s debt plan, leveraging their support to secure backing for a strong central government.

Shays’ Rebellion was quashed, much to Hamilton’s relief, but the conflict between struggling backcountry people and powerful eastern creditors and politicians persisted.

Democracy just wouldn’t shut up.

Hamilton’s Constitution: We, the Wealthy

When the U.S. Constitution was being drafted, the fledgling nation was grappling with severe economic instability, political fragmentation, and lots of jawing over the balance of power between a strong central government and states’ rights. Hamilton lobbied for a lifetime monarch and no states, while Thomas Jefferson pushed for stronger state governments and a decentralized federal system to prevent tyranny from too much central power.

But it wasn’t just Hamilton v. Jefferson. Regular people were fighting, too. There was grassroots agitation and demands for protections against potential government overreach, leading to the inclusion of the Bill of Rights as a safeguard for individual liberties. The implementation of mechanisms like the House of Representatives and state legislatures to ensure broader public representation and accountability was a win for the common folks, too.

But the Constitution was, on the whole, a Hamiltonian blueprint, forging a powerful central government and financial system that cemented elite control and financial dominance. Hamilton didn’t get his king, but the Electoral College and the Senate’s equal representation ensured the rich kept their grip on power by diluting direct popular influence. Slavery was entrenched through the infamous Three-Fifths Compromise. Women were given no rights or protections (Hamilton’s views on women were traditional and restrictive, in sharp contrast to the feminist views of his future nemesis, Aaron Burr).

The Constitution was a rigged game, setting up a system that protected property interests, maintained elite power, and avoided reforms that could challenge the economic status quo. The firebrand Herman Husband denounced the American nationhood emerging from the Philadelphia convention as a bail-out for the investor class, leaving the free-laboring many at the mercy of money and punitive law. He detested the fact that the document baked the institution of slavery right into the nation’s future, and enabled outright conquest of the confederated western nations and suppression of the citizenry by a national army.

Hamilton played a pivotal role in the battles over the ratification of the Constitution and was a major contributor to the renowned Federalist Papers. From his perspective, the outcomes were pretty favorable, given the circumstances.

Crushing the Small Fry for Big Business

In 1789, Alexander Hamilton became the first Secretary of the Treasury, setting his focus on repaying creditors and boosting commerce while consistently sidelining the needs of wage earners and small-scale farmers.

His 1791 whiskey tax perfectly showcased Hamilton’s detachment from – even contempt for — the struggles of everyday people. Ostensibly aimed at reducing the national debt, Hogeland argues that the real aim of the whiskey tax was to crush rural farmers who relied on whiskey production as a vital cash crop.

On the frontier, whiskey was the unofficial currency—since cash was as scarce and banks were miles away. Farmers turned excess grain into whiskey to boost their income, and it became the ultimate trade asset. Hamilton, ever the centralizer, saw this as a threat to his dream of a tightly controlled financial system. His solution? Smash the small guys and clear the way for big businesses. In the South, that meant forced labor; in the North, grueling factory shifts. All to ensure that big producers could trample the little guys underfoot.

Hamilton wanted more of the little guys working in factories. Hogeland notes that factory work in early America, largely performed by women and children, involved backbreaking fourteen-hour days, six days a week. Hamilton admired Britain’s use of child laborers and saw the whiskey excise tax as a means to move labor from farms to factories, including families and immigrants. Washington was on board with that, only noting that manufacturing could expand without displacing agricultural work.

Hamilton’s vision, reflected in Rhode Island’s factories using child labor, ended up pushing more people into tough industrial conditions and worsening the already harsh situation for women and children.

In Hamilton’s world, unifying the country meant funneling cash from everyone but the rich, with taxes and fees filling the pockets of top-tier economic players—mainly merchants and big lenders—who would use that money to drive national growth and boost their own profits.

His whiskey tax pushed out small distillers and turned grain distilling into a major U.S. industry, allowing federal power to consolidate wealth, weaken resistance, and build an industrial economy dominated by the commercial and investing class.

The tax hit ripped through the livelihoods of countless farmers and workers, creating a raw, visceral response from people who saw Hamilton’s policies as a blatant disregard for their economic realities. The Whiskey Rebellion, stoked by Herman Husband and local leaders like William Findley who rallied outraged farmers and distillers, was brutally put down when the federal government unleashed a large militia force that not only crushed the uprising with overwhelming firepower but also resorted to torturing and executing rebels to quash dissent and intimidate any further resistance.

Though the Rebellion was subdued, Westerners persisted in their fight against commercial monopolies, land grabs, and Eastern elite dominance. This infuriated figures like George Washington, who had to evict settlers from his land. Hogeland recounts a vivid moment when General Washington, recently celebrated for his great victory, became enraged during a meeting with said settlers and started swearing—only to be fined on the spot by a local justice of the peace for his public outburst.

But what about Jefferson? Wasn’t he the man who wrote the words “all men are created equal”? Didn’t he champion the small yeoman farmer? Hogeland, in a recent conversation, pointed out that Jefferson may have written those words, but he certainly wasn’t imagining they’d build a government that would elevate all classes to equal status.

Hogeland pointed out that while Jefferson talked a good game about championing small farmers, he was pretty out of touch with their real lives. By the time Jefferson’s ideas were put into practice, they mostly amounted to a diluted version of Hamilton’s approach.

“Jeffersonianism doesn’t really offer an antidote to Hamiltonianism,” Hogeland said. “Hamilton crushed the working-class movement with military force, making him the villain. But then Jeffersonians just co-opted and erased that movement. In the end, you get Andrew Jackson—who, despite carrying on Jefferson’s legacy, was far from a democratic hero. He was the first president to use federal troops to break up a strike.”

Challenging Hamiltonianism

In the end, Hamilton’s financial schemes to build the economy were predicated on a power grab for the wealthy. His policies deepened income inequality, leaving everyday folks struggling. His legacy shows how economic growth often tramples on social equity. As Hogeland reminds us, the myth of Hamilton as a champion of upward mobility not only romanticizes him but also insults him—he saw democracy as America’s biggest threat.

Hogeland notes that while Chernow’s biography helped turn Hamilton into a celebrated hero, the myth-making started long before. Figures like Bill Kristol had already lauded Hamilton as the savvy counter to libertarianism—someone who wielded government power to push his economic agendas. “It ended up crossing party lines with Robert Rubin and the Brookings Institution,” said Hogeland, “as well as people in the Clinton and Obama administrations taking up Hamilton as an avatar for liberal democracy — all of it feeding into a kind of cult in policy circles going right into the financial crisis, where Tim Geithner saw Hamilton as a guiding spirit for the bailout.”

Hogeland observes that Geithner’s bailout was meant to stave off another Great Depression, yet it echoed the foreclosure nightmares of Hamilton’s era. “This ‘what’s good for Wall Street is good for everyone’ mentality came to a head during the Obama years,” he said, “showing Hamilton’s approach as a way for elites to benefit on the backs of ordinary people.”

Hamilton thought his methods of boosting the national economy would eventually turn out well for everyone, much like those who, during the 2008 financial crisis, believed that what was good for bankers was good for all. But if you ask ordinary people, it didn’t exactly turn out that way.

During America’s crises—whether it’s the founding era, or modern crises like the 2007-8 financial collapse and the pandemic—too many have fallen into debt and poverty while the wealthy soared. Today, both parties claim to represent the common folks, but rarely do they act against elite interests. This is Hamiltonianism at its core.

The good news is that there are inspiring legacies from the founding era that challenge this perspective: Thomas Paine’s calls for progressive taxes, Herman Husband’s push for a form of Social Security, and Thomas Young’s advocacy for labor rights. Modern movements like Occupy Wall Street, fast-food worker strikes, women’s rights campaigns, anti-monopoly movements, and Black Lives Matter are all examples of democracy fighting back against elite control in their spirit.

Hamilton’s financial blueprint might have rigged the game in favor of the rich, but democracy hasn’t yet given in — many today are still scrapping with the entrenched elite, determined to wrestle back a fair shot for everyone.