In 1898, upwardly mobile Blacks in Wilmington, NC were terrorized and slaughtered in a violent insurrection that set the stage for Jim Crow – and the next 123 years. Hardly anyone really knows about it.

If you were a Black person in America in the 1890s, you wanted to live in Brooklyn.

Not Brooklyn, New York. No, you wanted to be in the bustling Brooklyn district of Wilmington, North Carolina. At that time, 25,000 people lived in the thronging Cape Fear River port, the state’s largest city. More than half of them were Black. In Brooklyn, you could meet Black seamstresses, stevedores, cobblers, restauranteurs, shop owners, artisans, midwives, merchants, doctors, lawyers, bankers, and police officers. The federal customs agent was Black. So was the county treasurer. And even the town jailor.

Wilmington was the most racially progressive city in the South. It was America’s future.

But very soon, it would be awash in blood — transformed into the country’s traumatic past. This repressed and unresolved trauma haunts the present in a thousand ways, most recently in the shocking siege on the U.S. Capitol. It continues to damage us all.

Here is the story of what happened, and why we need to talk about it.

Black American dreams

By the 1890s, Wilmington’s upwardly mobile Black community had been blossoming for decades, its seeds planted during slavery. In the antebellum period, enslaved Blacks in urban homes and plantations were often highly skilled. They moved about more freely than their rural counterparts, mingling with the townspeople. Some could even read and write.

Black people were the lifeblood of Wilmington. Black sailors and navigators made the city’s prosperous trade hum along, and the railroads and other businesses relied on enslaved and free Black workers. The city’s stunning architecture was the handiwork of Black masons, builders, and carpenters. Landmark structures like the Classical Revival Bellamy Mansion, which still stands today, were built by enslaved and free Black artisans. According to David Zucchino, the Pulitzer-prize winning author of Wilmington’s Lie, an essential account of the events of 1898, the city had nearly 600 free Blacks, artisans and tradesmen, before the Civil War.

After the war, Blacks poured into the city seeking work and security. By 1880, they made up 60% of the population – the most of any sizeable southern city. (Atlanta, by comparison, was only 40% Black). By the 1890s, a Black person could find opportunity at every rung of society. Many reached the middle class, and a few accumulated significant wealth. Cultural life was blooming. You could see Black people joyfully celebrating the Emancipation Act every year and putting on masked parades on the traditional Jonkonnu holiday.

White and Black people often lived and worked peacefully side by side in Wilmington. Most astonishing of all, some even began to vote together.

A Coalition Like No Other

After the Civil War, the position of Black people in North Carolina rose and fell. Some achieved prominence, like state senator Abraham Galloway, who refused to step aside for white men on the streets of Wilmington and openly carried a pistol.

But it wasn’t long before the white Conservative Party began to recover lost ground, especially after Reconstruction. In the 1870s, these whites began a program of “Southern Redemption” to expand power by keeping Blacks out of politics. There was a problem, though: Democrats, as the Conservatives came to be known, had earned the wrath of white small farmers pummeled by economic recessions. Some ditched the Democrats for the new Populist Party.

In 1892, a new crop of progressive Democrats, like young Raleigh newspaperman Josephus Daniels, challenged the elite planters and wealthy industrialists in their party so resented by the Populists. But white farmers and laborers were still too disgusted with Democrats’ support of railroads, banks, and other powerful interests to come back into the fold.

The Democrats’ worst nightmare came in 1894 when North Carolina witnessed something seen nowhere else in the South. A new party, the Fusionists, forged a coalition of Republicans, Blacks, and white Populists to beat a common foe – the Democrats. In most of the country, Populists tended to ally with Democrats, but not so in North Carolina.

It wasn’t that white Populists had much love for Black people. Most didn’t. But they disliked another group even more: the fatcat railroad barons, bankers, lawyers, and manufacturing kingpins getting fatter at their expense. The white working class was fed up and did the unthinkable, teaming up with Blacks and Republicans to support the same candidates.

North Carolina’s Fusionists routed the Democrats in the elections of 1894, taking control of the state senate, the house, and the courts. The new Fusionist legislature pushed through reforms that expanded registration, voting, and local governing opportunities for Blacks. Members even voted to honor the recently-deceased Frederick Douglass — creating such a stink among conservative whites that the government quickly erected a Confederate monument in front of the state capitol in Raleigh – recently removed in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

For Blacks, the future was looking bright. In 1896, North Carolina attorney George Henry White became the only Black in the U.S. Congress at the time. Blacks boasted 300 magistracies across the state, and they were becoming a powerful political force on the coastal plains where most lived, holding 1,000 offices altogether. In the 1896 local election in Wilmington, a whopping 87 percent of eligible male black voters turned out, giving America one of its first mixed-race municipal governments.

That’s when whites began to get really nervous.

“A bomb getting ready to explode”

Progressive Democrat Josephus Daniels was an ambitious young entrepreneur, not unlike the Silicon Valley upstarts of our time. Along with William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, he shaped the modern newspaper, figuring out how to use the media to pull the strings of politics. Some wondered why he didn’t run for office. The answer is that he didn’t have to. By his early thirties, Daniels had the reins of the most influential media platform in the state, Raleigh’s News and Observer. He was hellbent on using it to defeat the Fusionists.

As biographer Lee Craig outlines, progressivism for Daniels meant railroad regulation, agricultural reform, and prohibition. In theory, he was sympathetic to the plight of working class whites and used his paper to criticize the railroads and J.B. Duke’s American Tobacco trust. But he also knew the Democrats weren’t really going to quit making rich white men even richer. And he knew the Fusionist alliance was shaky, particularly on race. The newspaperman saw that the poorest whites were the most likely to begrudge Black economic progress. So Daniels decided that progress would mean sacrificing Black people. It meant white supremacy.

In 1898, Democrats across the state agreed to run on racism for the upcoming elections. Daniels supplied the propaganda for the white supremacy campaign, while his cohort, political organizer Furnifold Simmons, spewed racism on the stump.

Stoking resentment of Black prosperity wasn’t difficult. Edward A. Johnson, a Black alderman of Raleigh, reported that “Negroes in Wilmington had pianos, servants, expensive carpets, lace curtains at windows” and that “White Supremacy orators of that city constantly asked from the platform, ‘How many of you white men can afford to have pianos and servants?’”

Wilmington community activist Hollis Briggs, Jr. recently put it like this: “African Americans actually controlled the commerce and when you’ve got a race of people that control commerce and that were well off…then you’ve got a whole other group of people that were upset by this economic boom for African Americans. What you had was a bomb getting ready to explode.”

On top of this, the Democrats added themes of domination and sex. White people had to be riled up over the threat of “Negro rule.” Daniels went all out, giving North Carolina a master class in the dark arts of disinformation. His reporters dug up racist dirt. They picked up tall tales about Blacks in taverns, ran them as news. Every day, the News and Observer dished up false reports and flagrantly racist editorials. North Carolina will soon become a Black republic. Black people are buying guns to kill you. Hip to the power of images, Daniels printed grotesque cartoons that demonized Blacks— literally. A famous one shows a Black man as a hideous vampire bat terrorizing white people.

But all that still wasn’t enough. Whites must be scared by something even more farfetched — the bugaboo of the “black beast rapist.” Daniels sought to play on the white working class sense of aggrievement and emasculation in a way that would make them forget their hatred of fatcats – at least temporarily. He hit upon the lie that did the trick: Black men are coming to rape your women.

In the summer of 1898, Daniels received a gift in the form of an editorial written by Alex Manly, the mixed-race editor of the Daily Record, the paper of the Wilmington’s striving Black middle class. Manly had responded to a call for the lynching of Black men accused of raping white women by puncturing the biggest taboo in the South. He pointed out that white women were sometimes quite willing to have sex with Black men, just as white men were quite willing to have sex with Black women. Manly’s editorial was reprinted in newspapers across the state, along with feverish claims that the editor had besmirched the virtue of white women.

White people went berserk.

A coup, not a “riot”

In late October 1898, white supremacists in Wilmington got the perfect leader for their repulsive campaign. Alfred Moore Waddell was a former congressman – and a lawyer who defended lynchers, as Zucchino indicates. His specialty was giving rabble-rousing speeches to foment racism.

Waddell and his fellow white supremacist Democrats hatched a plan for the city. They would rig the outcome of the 1898 elections by intimidating Black voters, peeling off Populists, stuffing ballot boxes, and whatever else it took. But that wouldn’t suffice, because there weren’t many local elections in Wilmington that year. After November 8, many Blacks, Fusionists, and Republicans would still be in office. Waddell & Co. didn’t plan on waiting until the next election to get rid of them.

The solution was to execute an insurrection. The top men of the white supremacist campaign secretly agreed that after the election, they would overthrow Wilmington’s bi-racial government and install white officials in their place.

In the lead-up to November, the campaigners didn’t just hint that violence was coming if the elections didn’t go their way. They came right out and said it: Wadell stated, “We will never surrender to a ragged raffle of Negroes, even if we have to choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses.”

What they didn’t say is that violence was coming even after the election went their way.

As Zucchino details, white supremacists were more than ready for bloodshed. They had two militias, the Light Infantry and the Naval Reserves, consisting of soldiers just returned from the Spanish-American War and itching for a fight. Instead of answering to the white Republican governor as they were supposed to, they reported to the white supremacists. The Democrats also had a paramilitary group known as the “Red Shirts” that terrorized Black communities.

As the election approached, Wilmington looked to be preparing for a siege. Whites stockpiled every possible weapon, including a Colt rapid-fire machine gun for the Infantry, the deadliest weapon of the day. Meanwhile, Blacks were denied the purchase of guns and powder, even by sellers outside the state.

Black congressman George H. White pressed President McKinley to prevent the coming bloodbath, but no help came. The Republican Governor Daniel Russell was in fear for his own life, and would do nothing to stop it.

On election day, things went just as the Democrats planned. Through fraud and intimidation, they “won” across the state. Some thought that violence in Wilmington had been avoided, but they thought wrong.

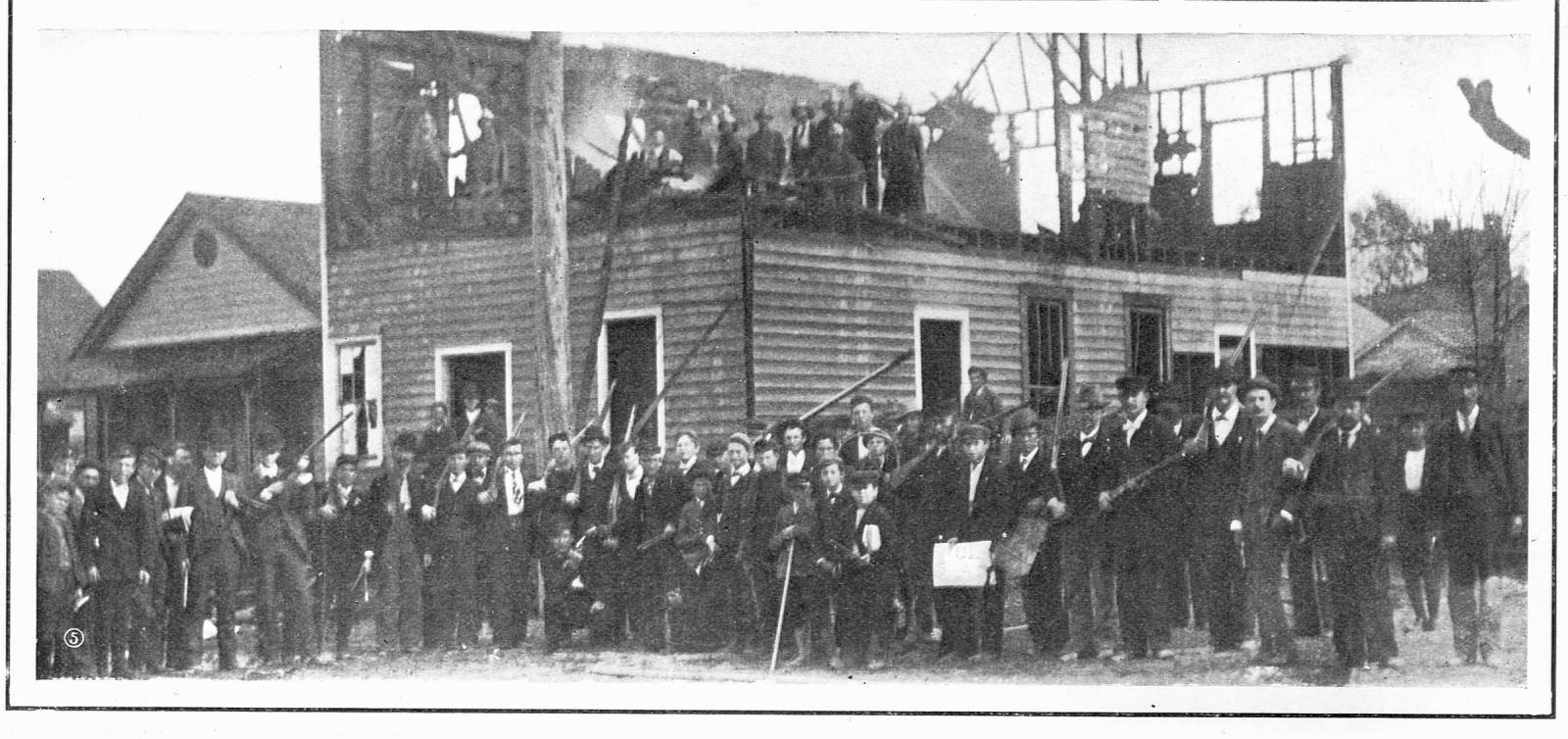

Two days later on November 10, all hell broke loose. But not in the sense of a spontaneous “riot,” as newspapers across the country described it, and many history books still do. No, this violence was long in the planning. Wilmington’s white supremacists used the pretext of a false threat of a violent uprising among the Black population to unleash a mob of 1,500 whites, led by the Light Infantry militia, to wreak havoc. Armed to the teeth, the mob headed to the Daily Record, hoping to lynch Alex Manly. He had already fled, so they burned the building. The mob swarmed on the Black neighborhoods, targeting Brooklyn in particular, murdering untold numbers and chasing hundreds out of town as they went.

By day’s end, Black bodies were strewn across the streets and gutters. Zucchino puts the number of fatalities at 60; some think it was even higher. The more prominent Blacks were put on trains out of town at gunpoint, ordered never to return. The poorer ones fled to swamps and cemeteries outside the city, where they froze and starved for weeks.

Some professional Blacks and white Fusionist politicians hoped to wait out the violence. They calculated wrong. The coup leaders banished everyone they didn’t want around, and some of the banished didn’t make it out alive. Zucchino reports that one popular Black barber was put on a train and found dead hours later, shot by a Red Shirt. A white Fusionist on the banishment list found himself hanging from a rope, only surviving by squeaking out the Masonic distress cry. He was saved by a fellow mason in the mob.

As the insurrection unfolded according to plan, Waddell named himself mayor and put white supremacists in the place of duly elected officials, including aldermen, 100 police officers, the city clerk, the treasurer, the city attorney, and anyone “whose affiliation with the Fusion-negro regime made them obnoxious to the people and the present administration.”

For the once-prosperous Blacks of Wilmington, whose only crime was success, the future suddenly grew dim. Zucchino writes that “the city’s black middle class, built and nurtured for decades, was collapsing. Hundreds of black families were homeless. Those who remained were by now thoroughly intimidated, accepting of white authority, and thus welcomed by whites to remain in Wilmington.”

The poor Blacks hiding in the swamps and cemeteries were eventually lured back because the whites in Wilmington couldn’t manage without their cheap labor. Plus, white supremacists dearly loved having Black servants.

A turning point in America

Wilmington’s Black community was thoroughly devastated by the coup. By the 1900 census, the city was majority white. Blacks continued to flee as the years passed. Today, the Black population stands at less than 19%.

After 1898, no Black citizen held public office there again until 1972.

The Wilmington coup stands as the only successful and lasting armed overthrow of a legitimate municipal government in American history on U.S soil. It was a horrific turning point for the country, marking the beginning of Jim Crow and poisoning race relations to the present day. Not only was it a stain upon North Carolina, but on the federal government, too, which knowingly abandoned Black people to death and destruction.

Yet if you ask most Americans, they know little about it.

This is partly due to the barrage of fake news about events circulated in the media at the time around the country, from Raleigh to Philadelphia to New York City. To help correct the record, in 2000, North Carolina’s General Assembly established the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission to investigate. The commission released its report in 2005.

One of the commission’s goals was to study the economic impact on Black people in Wilmington and the state. The report cited such problems as capital losses, less funding for education and thus lower literacy rates for Blacks, and broken support networks. Duke University economist William Darity, a member of the commission, discussed the economic catastrophe in the documentary film, “Wilmington on Fire,” He describes a blow that resulted in a significant decrease in the overall status of Black jobs in Wilmington and a steep decline in overall economic prospects. Going forward, the city had more Black service workers, fewer artisans and entrepreneurs. Middle-class dreams were shattered.

Commission member Harper Peterson said, “Essentially, it crippled a segment of our population that hasn’t recovered in 107 years.”

Today, Black Americans still suffer from economic despair and exclusion from the American dream. They still face brutality from authorities, attacks on their civic rights, twice the unemployment rate of whites, and a pervasive, structural wealth gap born in part of events like the coup and their aftermath.

Woodrow Wilson and FDR

Nobody was ever prosecuted for the Wilmington insurrection. White supremacists didn’t just get away with murder and treason in 1898. They were richly rewarded for it, in the South and beyond — none more so than Josephus Daniels.

Biographer Lee Craig notes that Daniels remained unrepentant about the white supremacy campaign even half a century after the fact. But that didn’t seem to bother the U.S. presidents who relied on his good counsel.

One fan was Woodrow Wilson, whose family moved to Wilmington when he was a teen. There, Woodrow enjoyed hanging out with the scions of planter elites, and as president, he remembered his North Carolina friends, saving the best for Josephus Daniels.

President Wilson made one of the key architects of southern apartheid his Secretary of the Navy. Daniels became, as Craig observes, “one of the few men Wilson held in high regard and consulted throughout his eight years in the White House.” The unapologetic white supremacist created the war machine that helped win World War I and oversaw the aggressive expansion of U.S. military power in Nicaragua, Mexico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba.

That’s not all. The man known as the father of Jim Crow launched the career of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who served under him as assistant secretary of the navy. When FDR became president, he still fondly referred to Daniels as “Chief, and awarded the treasonous criminal with an appointment as his Ambassador to Mexico, a key position. President Roosevelt described Daniels appreciatively as “a man who taught me a lot that I needed to know.”

In 2021, when a mostly white mob stormed the Capitol in Washington, some wielding Confederate flags, a few astute observers understood the evil echo of what had happened over a century before. Academics Kathy Roberts Forde and Kristin Gustafson summed up the parallels of the Wilmington coup and the capitol siege: “Each was organized and planned. Each was an effort to steal an election and disfranchise voters. Each was animated by white racist fears.”

There have never been reparations for the descendants of those victimized in the Wilmington coup and massacre.