The workshop derives from the realization that, because scientific identities were shaped at a time of disciplinary entrenchment in the postwar period, social scientists and historians of science alike have difficulty understanding the contribution of cross-discplinary projects to creative scientific work and, possibly, to the structuration of disciplinary identities themselves. The program included papers on area studies, behavioral science and empirical studies of decision making, the cognitive turn in linguistics, international relations at Chicago, and architecture at MIT in the postwar period. By the end of the day, a common underlying thread seemed to emerged in several of the papers and discussions: the multi-faceted ties between cross-discplinary ventures and education.

Such link was very clear in David Engerman’s paper on area studies (the use of an interdisciplinary approach drawing on sociology, economics, psychology, political science, cultural studies, geography etc. to study a specific geographic area, region or culture). Indeed, his claim is that area studies should be understood first and foremost as a pedagogical venture. This viewpoint enables Engerman to sidestep claims that areas studies were not productive in terms of research output. The purpose of area studies, he claims, was not merely to produce new forms of knowledge and expertise, but rather to produce better trained experts. He accordingly shows that postwar area study programs put heavy emphasis on language techniques, but also cultures, histories and politics of the regions concerned, with the purpose of training future international civil servants for the new world responsibilities the US had gained with the end of World War Two. I would have been interested in learning whether such programs were embedded in university departments or proposed by dedicated research centers. I had the feeling, from previous readings, that most cross-disciplinary ventures took place outside the university structure narrowly considered ( the Survey Research Center and the Mental Health research Institute at Michigan, the Center for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences, the Center for International Studies at MIT). In the forties to sixties, departments were moving toward more disciplinary specialization, and they were reframing their curricula, with the threat that giving broad interdisciplinary and practically oriented training to students would become a side concern.

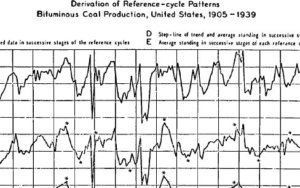

Michael Rossi’s survey of the uses and status of the phrase structure or tree diagram that figures prominently in the cognitive turn in linguistic intiated by noam Chomsky in early fifties also highlighs the relationship between science, interdisciplinary dissemination, and education. Rossi shows how, just as other visual objects in science (fi the Feynman diagrams investigated by David Kaiser), the tree diagram served as a tool for profession building, a weapon in academic arguments (cf Latour’s theory of inscriptions), a means whereby linguistic thinking was “reified” (Kaiser’s term) and in turn framed how linguists represented their objects, and a pedagogical device. According to his paper, it was also a major vehicle whereby the new linguitics of Chosmky was disseminated to other disciplines. The questions of the audience focused on the research vs pedagogical nature of the tree diagram: were the diagrams merely involved in, or supported or were even crucial to the transformations of linguistic? Did those diagrams foster the emergence of a common language? If they were a primary tool of graduate pedagogy in linguistics, can they be seen as a crucial dissemination mechanism of the cognitive turn? Did the diagrams travel from pedagogy to research or the other way round? (Such questions are akin to those Yann Giraud, fellow blogger, asked in his PhD on the changing place of visual representation in economics. For instance, he analyzed the status of diagrams such as the keynesian cross or the circular flow diagrams in Samuelson’s writings, the Laffer curve, and the uses of diagrams in economic textbooks).

In her paper on the evolution of architectural expertise at MIT in the 60s and 70s (which I have already mentionned in a previous post), Marylou Losbinger explains how computer enabling design techniques were introduced into architecture by those academics who wanted to make their science more rational and suited to the interdisciplinary ventures they were increasingly associated with (urban planning etc..). Such change in the practices and thinking of architecture required and depended on the evolution of architecture education: MIT architects sought to supersede the Beaux-Art teaching style of the fine arts atelier and the Bauhaus pedagogical methods by instilling computer based solving approach both in lab and “design studio’ training and practices.

MIT design studio, picture borrowed from the blog “life of an architect”