Stabilized or not, China’s target of 7.5% growth marks a steep slowdown over recent growth rates.

Other major economies, facing weak demand, currency crisis, and high unemployment, have pushed monetary policy to the hilt with various forms of central-bank balance sheet expansion—QE3 in the US, OMT (announced, not yet used) in the euro zone, and maintenance of a currency peg in Switzerland. What about China?

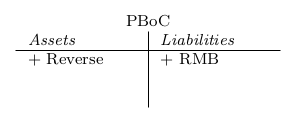

The PBoC has certainly not been sitting still. Earlier this week it lent RMB 30bn ($5bn) to the money market, on the heels of a near-record injection of RMB 265bn ($42bn) into the Chinese money market earlier this month. This has come in the form of reverse repo operations:

It is worth remembering what is the immediate effect of such injections on the financial system. In a contracting economy, borrowers are coming up short, unable to meet their maturing obligations as they come due (in China as in any financial capitalist economy). The strain falls onto the banks, who can absorb it when the shortfalls are small. When the shortfalls become too large to be absorbed by any one bank, the biggest bank around, the PBoC, can create new money to meet the strain, which is the economic substance of these short-term liquidity operations.

They have been successful in pulling down overnight interest rates, but not at even slightly longer tenors, including the normal measure of Chinese interbank conditions, the seven-day repo rate. The RMB 265bn ($42bn) injection was enough to bring down the seven-day rate by just 3bp. One problem is that the reverse repo operations themselves have a fairly short term, and so they will have to be refinanced or unwound over the next few weeks, depending on whether the PBoC continues accommodation.

The context of all of this is the question of whether China will be able to rebalance incomes in its economy away from investment and toward domestic consumption. If the current high level of investment is unsustainable, it will surely come to an end. Coming to an end means, practically speaking, that producers of capital goods (and inputs to those goods) will be coming up short at the end of the month.

There is evidence, albeit anecdotal, on this score. In his latest newsletter, Michael Pettis points us to Bloomberg:

Copper inventories at bonded warehouses in Shanghai probably climbed to a record as import premiums dropped to a four-month low, signaling demand in China may not be improving as much as expected after a summer lull.

Other similar stories can be found. Simply put, as investment spending falls, industrial inputs like copper will go unsold. Inventories will pile up, and producers will find it hard to pay their bills. This will in turn bubble up as unmet obligations and, ultimately, liquidity strains in the banking system.

There are two ways out: either chronic shortfalls leading to bankruptcies in the capital-goods sector and contraction of investment, or sufficiently rapid growth of consumption to rebalance the economy without allowing capital-good production to contract.

The trouble for the PBoC is that, in the first case, the shortfalls are not going to go away in seven days or even in three months, so liquidity is no help; and in the second case, a major structural change needs to play out, so liquidity is still no help.

China has avoided large-scale stimulus in the current cycle, perhaps looking ahead to the Party Congress and leadership change in November. So perhaps the PBoC, not entirely unlike the Fed, feels that monetary policy must be used, even if fiscal policy would be more appropriate under the circumstances.

The Fed, the ECB, the SNB, and the PBoC have taken stock, and each has decided that large amounts of liquidity are called for. Rough seas ahead seems a safe prediction.