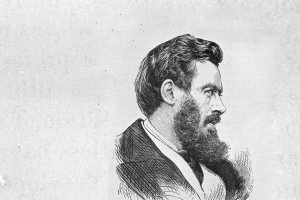

Boston University economics professor Perry Mehrling discusses his recently released INET book, in collaboration with Cambridge University Press, “Money and Empire,” which chronicles the life of Charles P. Kindleberger and how he helped shape the emerging global dollar system

VIDEOCAST

Transcript

Rob Johnson:

Welcome to Economics and Beyond. I’m Rob Johnson, president of the Institute for New Economic Thinking. I’m here today with my colleague, Perry Mehrling, who has been at the vanguard of the formation of the Young Scholars Initiative, that made an enormously successful course on money and banking, that’s been on a number of platforms and has really been at the core of the evolution of INET since it was formed at the time of the great financial crisis. We’re here today to discuss his newest book, which is called, Money and Empire: Charles P. Kindleberger and the Dollar System. As he mentions in the preface, I am a person who is very, very grateful to Charles Kindleberger.

I had joined as an undergraduate at MIT with the intention of being a naval architect, and Charles Kindleberger inspired me to move in the direction of curiosity, economics, economic history and financial economics, and had a very, very big impact on my thinking and my career. Perry, thank you for joining me today and I’m looking forward very much to what your insights are about this man who helped shape my life.

Perry Mehrling:

It’s good to be here. Thank you for inviting me.

Rob Johnson:

I guess, I want to just start with how did you come to the place where you wanted to write about Charles Kindleberger and about his relationship to the world, to academia? What triggered your enthusiasm?

Perry Mehrling:

Well, I suppose it sort of parallels the creation of INET in a way. The initial proposal that I made in the first grant round, if you remember, was for a book that was tracing the rise of the global dollar system period. Kindleberger was not so much a part of that, that was meant to be a follow-up to my 1911 book, The New Lombard Street, which was about the financial crisis. And when I got started with that, I found the Kindleberger archives, I found some things also in the Modigliani archives, some conversation between them about the future of the international monetary system. I realized that I could tell the story in a different way, not as the story of the rise of the dollar only, but really through using his life as the arc of the story. So, that’s how it kind of got started.

The reason for doing the original project was that I felt that New Lombard Street, when I finished it, when I looked at it, I realized that the global financial crisis, I had told that story as a story of the biography of the Fed, that it was created in 1913 and it was a sort of a story of its adolescence and its growing through crises and up to the global financial crisis. So it was a story of that institution and I realized that what was missing really in that book was the global story, because I’d focused so much on the Fed. So, that’s why I was trying to write the international money story. I also realized that my MOOC also, which also INET published, was originally about the US monetary money markets using Stigum and it wasn’t adequately international.

So one of the goals that I had in the last 10 years was to extend the money view to international and using this book as part of the vehicle for doing that, and therefore entering Charlie’s mind, Charlie seemed to me, when I found him at, “Here’s a guy who actually knows something. How does he know what he knows? How can I enter that mind? How can I build on what seemed to me a very wise person?” So I had selfish reasons for it. There are a number of reasons converging for why to write this book.

Rob Johnson:

You start the first segments of the book about the formation of Charles Kindleberger’s career of life understanding and so forth. I guess as the Institute for New Economic Thinking, we’re always interested in how unusual a creative people came to life and how they interacted with the profession and what difference they made. So over the course of this conversation, I guess we’ll understand more if you can share with us what took place in the formative experience of Charlie Kindleberger that you think was important in who he became.

Perry Mehrling:

Well, the first four chapters are about that formation. I should also just alert your listeners that although this looks like intellectual biography, and it is an intellectual biography and that’s one of the reasons that people are interested in it, particularly people like you who knew and admired him. It’s also meant to be a history of the global dollar itself. All the events growing and it’s also meant to be a history of the evolution of economic thought. So in every chapter, these three stories are kind of intertwined. Sometimes one is more prominent. I think at the … so I’m trying to set the stage in the first four chapters, particularly for people who don’t necessarily have an economics background.

So I have to teach them a little economics. So my strategy there was to basically follow Charlie’s own education and to say, “How did he learn what he knew so that the reader can be educated in the same way?” So it’s important to realize, so he was born in 1910 and so he sort of came to maturity in the Roaring 20s in New York City, he was born in New York City. Then, the depression hit and that was a big effect on his family finances, and he was more or less alone in the world after that. His father was a very well to do lawyer who basically then clients don’t pay lawyers in the depression. So the family finances fell apart and he went to graduate school at Columbia.

So I think that those years in the wilderness, I guess, from 1933 to 1937 when he’s doing his PhD, are the formation and the key people in influencing him are H. Parker Willis, who had been … played a very important role in creating the Fed in the first place. I suggest, I came to believe that in a way, this was a role model for Charlie, that he thought he would use … that he would spend his life trying to create an international monetary system that was integrated in the same way that Willis had done for the United States, knitting together the different parts of the US, there had not been a central bank of course in the US until 1913. So, that sort of, I guess, young adulthood ambition, which is pretty large, I think helps to explain a lot of what he continued on doing.

So Willis was important, Angel was important, James Angel as an internationalist. American but an internationalist student of Allyn Young from Harvard, and I think he learned almost like a negative example from Angel, that Angel was a big supporter of the League of Nations, multilateralism, and that basically didn’t work. Not only because the Congress refused to join up, but remember, you know this, that in Charlie’s mature life, he emphasized the importance of leadership, of the United States as a leader, not multilateralism but more leadership. I think that was because of the disappointing example of Angel in a way. Then, most important I think was John H. Williams who was then a professor at Harvard, but he was vice president of the New York Fed.

So when Charlie got his PhD, he got a job at the New York Fed. There were no academic jobs. So, he was a central banker for quite a while, and John H. Williams was his sort of, not immediate boss, but was his thinking sort of infused the New York Fed at that time. In fact, his key currency, he was pushing this key currency idea as early as 1933 at the World Economic Conference in London, which didn’t go anywhere. He thought we needed to stabilize, pound against the sterling, not multilateral. Okay, so this idea of key currencies, it comes from John H. Williams and it was really, all the New York Fed was on board with that, but it didn’t happen until 1936, the Tripartite Agreement, which was to stabilize sterling and the dollar and the French franc.

That was really why Charlie was hired to be sort of a staff support for the data behind that. So that’s how he started his career, was working toward international monetary stabilization, inside the Fed, as a staffer, which he did for a couple years and then, he moved to the BIS in Basel, which he had hoped to be for a long time, but war interrupted that. He came back to the New York Fed … sorry this time, to DC, to the Board of Governors and worked with Alvin Hansen for a while. Then, had a good war. He was in the OSS in London, and I tell that story in chapter three. I think that’s a lot of where his empirical approach to the world got started and his willingness to form a narrative.

A view on the basis of disparate kinds of pieces of data that you don’t need a complete time series or to give advice to the generals about where to bomb in order to hurt the German war effort. You can’t wait for all the data. You have to take … piece together this and that. I think his intellectual formation that was very key for the style when he became an economic historian later on, that that was the style that he was and not … I mean, he was not really one ever for digging in the archives. He was reading all the stuff that other people dug up. They were like the field reports coming in from … that he was an intelligence analyst, sort of putting together, “Well, what does this all add up to?”

So I think that was an important formative too, and of course, that’s not really …. it’s not an economics job, it’s an intelligence analyst job. He was cleared for Ultra. So he was a very high ranking intelligence officer and traveled with General Bradley after D-Day on the continent and then, came back in the State Department and was the head of reconstruction of Germany and Austria, the division inside the State Department and ultimately, worked under General Marshall in getting together the legislation for the Marshall Plan, which almost killed him, it was so much work. Then, he started his academic career in 1948. So all of that stuff, you were asking about formation. This is a guy who has so many influences, before he’s 38, that he’s in the war and he’s in the State Department.

He’s in the Fed and he’s in the BIS, and the world is a chaotic time. So none of these influence are not integrated yet. They become integrated I think throughout his academic career that he’d had enough excitement. So sitting in his chair, in his office at MIT writing books was perfectly fine with him because he’d had enough excitement, I think, for the first 38 years. By then, he had four children too, so he just settled down and stayed there. You met him many years after that, but you asked about the formation. I think there is a sort of inspirational … I’m inspired by that, by somebody who couldn’t … he had to adapt. It’s not easy to have a life of a scholar, and so you try to do it where you can, at the Fed or in the State Department or even in the Army, so you’re adapting.

He’s a very resilient and I think sort of emotionally stable person not given to defeatism. This is where it was all formed in those early years. So my strategy in writing these books, this isn’t the first time I’ve tried to do this sort of thing, is I think the juvenilia is extremely important. Instead of saying, “Well, what are the most famous books? Let’s focus on them.” I say, “What are the least famous books? What are the stuff he was writing when he never thought anyone was going to read it?” Then you can find out where he came from, so I spend a lot of time on that, digging up details from his childhood and who his friends were and things like that, what life was like at Columbia and that period, and that’s not just idle curiosity or adding color. I think it helps to understand the mature man where he came from.

Rob Johnson:

Yeah. Well, as you have been, which I called shepherd and a key shepherd in the development of the Young Scholars Initiative. I think young scholars who are contemplating what direction to take in their career will benefit greatly from the journey you take them on in this book, to understand first of all, what you might call, formative experiences inspired him to go in these directions. Like you said, his family losing money, et cetera and the disorientation. The second being, which I called the inferences or the patterns he recognized from his experience in the field, and in the question of becoming an academic, I guess I would say he’s on a different trajectory than many people in the post John Hicks and Samuelson era where quantitative, particularly conceptual modeling is really at the vanguard.

When he comes to a place like MIT, he’s really interfacing with people whose quantitative skills are their gift and their focus. What was it like for him to be almost speaking a different language of economics than most of the faculty who were his colleagues?

Perry Mehrling:

Well, he joined MIT in 1948 and what we think of as MIT today as this high powered statistical modeling, mathematical modeling, that was really not the case in ‘48 yet, at all. In fact, I should maybe back up and say his idea of joining academia was to keep a foot in the public policy world that he had been in for 12 years. He had been a civil servant really and he wanted to basically do the same kind of work he had done in government except in the university now. So, he wanted to have a foot in both worlds. Then, because he lost his security clearance, he was unable to do any government work anymore, so he had to really commit to academia now. He had tried to get other academic jobs. He had interviewed at Yale and also at Princeton.

The faculty there, they were always … they responded negatively to him because he was supporting the Marshall Plan and they were saying, “All we really need to do, we don’t need the state involvement here. We should just let the market work.” So they wouldn’t hire him. Okay. MIT was willing to take a flyer on this guy, basically and he didn’t have a job interview really. They just took a flyer on him, and I tell this story about how that happened. I mean Samuelson knew who he was. Everyone knew … there were so few people in graduate school at that time. They all knew each other, and his first book, The Dollar Shortage was really the economics of the Marshall Plan. So he got tenured at MIT for exactly this argument about why we need the Marshall Plan, whereas other places weren’t willing to even hire him for it.

So they took a flyer on him and he always was appreciative of that. I think that … so some of the story I tell in chapter five about … I call it tech to remind people that MIT was tech, it was what they called it, back at the beginning. The department was an interdisciplinary department with political scientists originally. It separated later and got professionalized, and it was a service department to the engineers, which was most of the students at MIT and Samuelson’s famous textbook, which he wrote in 1948 was intended to be like, “Well, how can we teach economics to engineers?” Okay, well, engineers are used to this sort of training, so let’s create a textbook that’s appropriate for them. That textbook then became the bestselling textbook and took over all the departments.

I don’t think that was Samuelson’s intention at the beginning. It was really to teach economics to the engineers. There was other things about the early days in MIT that I uncovered. The importance of the interactions with the IMF, for example, that went both ways and his international economics experience, that was a way to get involved with policy work. When you can’t get hired by the US government, you could engage with the IMF and also, the World Bank and the BIS, he had been employed at the BIS and he never lost those connections. So when you say that it was a difficult time for him, I think that difficulty didn’t become … because of the changing morays of how to be an academic that didn’t really, I think, become a difficulty until maybe the early 60s or something like that.

Because it was actually 1966 when MIT made a very specific decision, the department, like we are going to really grab the brass ring and try to upgrade and be the place that ambitious young graduate students are going to want to come, and we’re going to provide this kind of training that will separate us from the pack. So it wasn’t really until ‘66 and at that time, Charlie is 56 and he goes along with this, but he realizes there’s not that much place for him in a department like that. So he tries to go into administration for a while at MIT, and he sees the writing on the wall with the student uprising and says, “I don’t think it’s a good time to be an administrator.” So he takes a year’s leave and goes to Atlanta to teach in the historically Black colleges. That’s when Martin Luther King is assassinated.

I think that was a big turning point in his life too, where he recommitted to the scholarly life. Instead of saying, “Okay, I guess I’m a washed up dinosaur,” he said, “There’s important stuff that’s happening,” and particularly also the dollar system was coming under attack at that time. So I think he recommitted, that year away was a period when he recommitted, and when he came back, that’s when he wrote The World in Depression. That’s when he started that line of thinking, which is what we remember him for, The World in Depression. Then, after he retired, 78 was … he was forced to retire in 1976 because of the mandatory retirement. So Manias, Panics and Crashes, which is probably his most famous book to the general public, was a work of retirement in order to make a little money because he didn’t had a rather meager pension.

Also, he’s on his own now. He’s no longer sort of, has to be a team player at MIT. He’s retired, so he can do whatever he wants. Then, the work that he calls his Che dovrà, The Financial History of Western Europe, it comes after that. Then, he’s elected to be the president of the American Economic Association. So he had a good … there’s a third career here that comes really after his official retirement and after he becomes sort of persona non grata, but not necessary. There was nothing he was adding to this MIT strategy, and that must have felt pretty bad for him. He had been a builder of this. He was employee number three or something. He was hired before Solow.

So he had really helped build this department that then had no use for him. He just took that and said, “Okay, I’ll do something else,” and that’s what he did. So you’re right to say that it is surprising to find somebody with this pre-World War II sort of sensibility at MIT, that is a little fish out of water, it was not so much fish out of water in ‘48. In fact, because he came from the OSS, you remember there were some scandals about CIA money going into MIT, but the CIA was the follow-up to the OSS. So I think that’s actually one of the reasons he was attractive to them, when they hired him, that he had this sort of clearance and this government experience, but then when he lost his clearance, he wasn’t useful for that anymore.

So he had to find another way. This is a story of resilience, of following an intellectual course and just doggedly getting up every day and going into the office and taking advantage of what opportunities arise and not getting discouraged by rejection, just find another way. So it’s pretty inspiring, I found. So young scholars, you’re speaking about young scholars, the … Yes. So this mathematical and statistical modeling kind of hegemony that’s taken over education is, every department, you have to get trained to a certain level. The question though is where do the ideas come from? I mean, these are techniques, so they’re techniques for … and where do your ideas come from?

I think that Charlie … there were people at MIT, graduate students at MIT who really did appreciate him as a man of ideas, that you could talk to him about your research. You then had to go to someone else to help you with the econometrics and the mathematical modeling. He could think without writing down equations. He could think without running regressions, and that was a pretty unusual skill. So that’s partly what the book is about, is understanding. Here’s a guy who was right about a lot of things, even when his more technically trained colleagues were not. Why was he right? How did he think about the world? What was it that he knew that I need to know? And I need to enter that mind. So that’s the payoff for me, is feeling like I know how he thought now and so I can do it, myself.

That’s what made it worth it for me. It’s not just because I like writing intellectual biographies. No, I’m trying to learn monetary economics, and he taught me in international economics really most of what I know now through this project. Not that I was ever his student.

Rob Johnson:

Yeah. I had the good fortune of coming on scene in the fall of 1976 at MIT and about a year later-

Perry Mehrling:

So he had just retired? He had just retired. Yes. Okay.

Rob Johnson:

Yes, but he was still teaching international trade-

Perry Mehrling:

Yeah, halftime. He was teaching halftime then, yeah.

Rob Johnson:

He was teaching a course related to the financial history of Western Europe with the Manias, Panics and Crashes infused in it. So I came from a family where my mother had a Scottish father and a German mother, and their professional lives were very disrupted by the Great Depression. So in the, what you might call folklore of my formative years, that the anxiety about finance was ever present. Here I am trying to be a naval architect and then, I come across this guy who seems to illuminate with The World in Depression and some of these other works that were in progress, the kind of concerns that had unsettled my mother’s life, and I think from which I call the echoes of her distress, it ignited my curiosity in a way that he, I would say, nourished me tremendously.

He was also extremely pleasant. He had groups of students of which he included me that he would take to the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s rehearsals. He got somehow … Seiji Ozawa’s team allowed him to bring in six or eight people to watch the rehearsals before they would start a new concert agenda. Then, we’d all have coffee afterwards. He was a very warm and magnetic individual. Then, as I said, dealing with these things that echoed to the concerns of my family. You had mentioned in a couple of times in this conversation that Charlie lost his security clearance, and I know that you’ve also had access to documentation and so forth in the archives that there was some anxiety related to, what you might call, his international connectedness or whatever.

In that kind of hard Cold War period, in the McCarthy age and so forth, what was going on there? What was going on that led someone with that much experience and successful experience losing a security clearance?

Perry Mehrling:

Well, you’re right, he got his FBI file through the Freedom of Information Act, which I believe was passed in ‘66 or something. So he wrote off for this, and initially they sent him garbage and he wrote off again. So, he finally got this file and so he eventually knew why he lost his security clearance, and he put those documents in the archives at the Truman Library, with serious archive. So, I was able to see it and read it. He wondered for a long time why he did, why he lost that, because he lost it in, I think it was 1951. Of course, they don’t tell you. They just say denied and that’s it. So of course, he had lots of interactions with people who were on the left and in the 20s, in the 30s, certainly New York was a very political place in the 30s. He had lots of acquaintances who were in various political groups. So he was wondering if that was the problem. What got him was it seemed that Hoover actually kind of went after him. He had been the-

Rob Johnson:

Hoover, you’re not talking about … you’re talking J. Edgar Hoover?

Perry Mehrling:

Yes. Not president. Yeah, yeah. Yes. As a graduate student, I mean, talk about sort of bad coincidence while Charlie was waiting to get this offer from the New York Fed, which he thought he would get because he had some inside connections, he was a loose end. So he took a summer job at the Treasury and under Harry Dexter White. So when Harry Dexter White came under suspicion, anyone who was connected with Harry Dexter White came under suspicion and he had put Harry Dexter White as … when he was applying for security clearance, he had put Harry Dexter White on an earlier application as a reference. So, this is somebody … and so this brought him to the attention of the authorities. So that was strike one, but then they investigated. Another strike was Robert T. Miller who was a year ahead of him at the Kent School and who was a friend of his wife’s brother.

So they kept in contact with him, and both Harry Dexter White and Robert Miller were brought before the House on American Activities Committee, really pretty shortly before Charlie was denied security clearance. So these were the two major things. There was a third strike, which was that somebody who wasn’t a member of the Communist Party, I think his name was David Wall or something, had included his name as people in the State Department who are friendly. So meaning probably that he wouldn’t hang up the phone on you or that he might talk to you or something, which of course he would. That’s who he was, but that’s not to say that he was working for the US Communist Party, much less a spy for Russia or anything like that.

Those were the three strikes that then ruled against him. Now, it turned out all that information was available to … already when he got the security clearance to work with the Marshall Plan, but the people who ran the Marshall Plan overruled it, and they said, “Look, we need this guy. None of this amounts to anything, so we are going to approve it.” So he thought that would happen again when he applied three years later, and it did not because there were different people who were reading the file, so he was denied. As I mentioned earlier, this is a devastating kind of blow for him, not only because he had been cleared for Ultra, he was a very high ranking intelligence officer, and all of that was very top secret and nobody even knew about Ultra until many, many years later.

He certainly didn’t tell anybody about it, but none of that mattered, and he had a bronze star. He was a kind of a war hero. So this was personally, I think painful, but it was more painful because it meant that he couldn’t have the life he was planning to have with a foot in both worlds. So he had to find another way, and I think many of his friends were also brought in under this, and their lives were also very disrupted by this witch hunt. Some of them lost their jobs permanently. So he was relatively lucky that MIT was not only willing to take a risk on him, but they were willing to give him tenure at a time when the witch hunt was getting people thrown out of their … so that’s another reason to be kind of loyal to MIT.

He was a loyal sort of guy in his character, but that’s also useful to remember that those times, that it’s swept in a lot of people who had really tremendous contributions to the United States, Government Service and to be not having their service, I think was loss to the United States and you see that as part of another obstacle he had to overcome.

Rob Johnson:

In his interactions at MIT, after losing the security clearance, did that create barriers to his collaboration with colleagues? Were they, if you might say, embodying a caution light about Charlie is not … there must be something unsavory, did it?

Perry Mehrling:

I don’t think in terms of the economics department, I don’t think that none of them thought that he was unsavory, okay? Samuelson, Solow, none of them. There was a very important impact, which is that Center for International Studies, which was sort of like the center of social science research at MIT took CIA money and you had to have a security clearance in order to be a part of that operation. So for example, Walt Rostow, who he hired, he had been a wartime buddy of his in London. While Rostow was part of that, and he couldn’t be a part of that. So he had to find his intellectual community basically down the river at Harvard or rather up the river, I suppose, at Harvard, at the Center for National Affairs.

So, he did, and he also taught at Tufts. Luckily, Boston is a pretty … there’s a lot of intellectual community that you can find if you look around for it and so he did, but I would say these are more institutional barriers than a notion that he was an unsavory character. Yeah.

Rob Johnson:

Okay. Yeah. I remember Charlie inspiring me to cross-register and take a number of courses at Harvard that were related to international affairs or the development of multinational enterprise, in particular, Richard Caves taught a course that was quite interesting and deep dive. And I remember he had a student, was it Stephen Hymer, who had written about multinational enterprise, and I read in your book that his work was not allowed to be published in the MIT series, but Kindleberger started us with reading that thesis and then, encourage us all to go to … over to Harvard to learn more in what he thought was an enormously important development for the future, which proved to be quite true.

Perry Mehrling:

Yes. So this role of the multinational corporation, I think it’s right what you say. So Stephen Hymer was Charlie’s student, not Richard Caves’ student, and just to be clear, he wrote his dissertation at MIT and Charlie was his supervisor, and he tried to help him get jobs in various places too, and he died tragically early. So, Charlie tried to continue some of that research agenda to keep it alive, make sure that people notice this. I think Charlie’s own interest in this … and he wrote even a little book, Business Abroad or something, a series of lectures. He included this in his international economics textbook. So here’s the point that remember, he’s thinking that there are forces leading to integration, global integration and universal money and so forth.

He’s thinking that the multinational corporation is one of them, that the nation state is opposing this, the nation state is trying to have its own polity, but the multinational corporation is a global thing. So he’s quite interested in that. I think initially, he thought that the … he took from Hansen this idea of secular stagnation, that the way to get global growth was to channel capital from the global north to the global south. So you needed to have capital markets, so that’s why the World Bank was always much more important than the IMF for project finance, in his mind. This was true of John H. Williams too. That wasn’t really happening very much. He saw, the multinational corporation initially as well, maybe this is a way through the internal accounting of a multinational corporation to channel capital to the global south.

When he looked at it with Steve Hymer, he realized that’s not a lot of what’s happening. What Hymer found is that these multinational corporations are sort of creating branches in these countries, but then they kind of are locally financed inside those countries. So there’s not a lot of capital flow, but they’re integrated in this … so they are an integrating factor, but it’s not the capital flow thing that Charlie was initially got interested in. So there you go, nonetheless. So that’s why he stopped sort of working on that, and it was really … so that’s something I don’t make very much of in the book because I’m trying to follow the money arc. It is definitely a story that is worth its own. That’s a spinoff, that could be its own paper, I think, to track that.

There was a lot of work there, a lot of books and conferences and things like that, and he collected it at all in a book called Multinational Corporation. So that was a lot of work that he did on that. Ultimately, it wasn’t part … I wouldn’t say it was central. It wound up not being central, once he learned how these corporations work. This is important to appreciate because … so he has these friends on the left. It’s very common on the left, of course, to be anti-globalization, anti-multinational corporation. So he got into trouble with some of his friends about this attitude that maybe in fact, the multinational corporation is a progressive influence in terms of economic development, in terms of globalization, in terms of integration. That was not a popular opinion, but he wasn’t shy about saying it because I think he believed it. He believed it.

Rob Johnson:

He brought a lot of things, I say to the table. When I first met him, I was, as I had mentioned, wanting to be a naval architect. He said to me, “Why don’t you add economics as a second major?” I said, “Well, okay, but that’s a lot of course.” He said, “No, if you take … if you’re good at math, you take the advanced micro, macro econometrics, you get nine courses for taking three because you take the advance, which qualifies you for the intermediate in the intro, so you’re down the path.” Then he said, “Then what you just got to do is a couple of interesting projects.” He had suggested I go over and meet Raymond Vernon about multinational stuff. Then, he kind of stopped me and he said, “I know with the OPEC crisis, you’re working with Morris Edelman.”

I was at what’s called Undergraduate Research Opportunities, UROP at MIT. He said, “I’m interested in Petrodollar recycling to the global south. How does the Middle East money get back to nourishing the LDCs?” The low developed countries as he called them? “How does that work?” Then, he said, “The sailing thing, you should bring that to economics,” and he told me he was interested in writing a book about how the pattern of trade in the competition between the Dutch and the British Empire was affected by the strategies of nautical technology in each country, particularly how …” how did he put it? “How a ship which was going to have precious cargo can protect itself.” He talked about how the British had put the guns on the boat so they could go to Asia, come back and protect themself.

Whereas the Dutch had essentially the equivalent of PT boats surrounding the boat that carried the … and so if they went on a long voyage, each PT boat would get picked off in different conflicts and then, essentially, the treasurer could be taken. He ended up asking me to write my junior paper on these differences in technology and so forth. He wrote a book, what’s it called? It’s like Maritime and Markets-

Perry Mehrling:

Mariners and Markets.

Rob Johnson:

Mariners and Markets.

Perry Mehrling:

That was long after he retired. In fact, when he moved to the assisted living community in Brookhaven.

Rob Johnson:

Yes.

Perry Mehrling:

And I think it was a work of therapy for him to … his wife have had a stroke and he had to leave his beloved house in Lincoln. So, it was returning to a childhood interest. He was an amateur sailor.

Rob Johnson:

That’s right. Yeah.

Perry Mehrling:

And he loved that. He often said that his only regret in life was that he never had enough money to buy a sailboat, but he rented sailboats sometimes and went on, and did these cruises with family and friends. When he was in college, he in fact, was on a merchant steamer two summers. So this was a summer job, traveling the world as a deckhand. In fact, he says a funny thing in his autobiography. He says, for me, international economics began in 1929. Of course, you might think, well, so it’s the Great Depression that made him aware of the … but that’s not right. That’s when he was on the first trip, that he got interested in the global world on these boats. He traveled to Leningrad and met the Soviet sailors. Of course, the crew in these boats is very international and then, pretty rough people too.

He loved it. That was an incredible adventure as a college boy, as a college boy. So sailing to him always had these other residences of … and I think there’s certain psychological resonances. When you’re a sailor so you know that you’re controlling these forces that could kill you, if you don’t control them correctly, and you could capsize, and you’re sailing into the wind too. So the wind is trying to push you this way, and you can actually go into the wind if you have the appropriate sails and so forth. So I think there’s a psychological satisfaction, and maybe we could think that he … I told you about his resilience, maybe in his life obstacles. Maybe another way to say it is that he was prepared to sail into the wind, and to find the setting of the sail that would allow him to make forward progress even when the wind is blowing straight in your face.

So that image, which is from childhood, sailing around Buzzards Bay, actually with friends, he was lifelong sailor, so it gave him something. There was something nourishing about that particular kind of sport.

Rob Johnson:

Well, that’s how he actually … I was a student in his class, but not outspoken in anything about sailing, but he had seen a picture of me on deck in Annapolis as part of an MIT crew at Obrigado where MIT had … I believe we were either first or second place, and it was covered in the school newspaper. When he asked me about this maritime technology becoming my junior paper, becoming a major, he also told me that the person who should be my advisor as an economics major was Bob Solow, who along with his wife, was basically spending summers in Martha’s Vineyard learning how to sail and was enthusiastic. He said, he’ll be enthusiastic about what you know, while you’re enthusiastic about what he knows. The first course I took was Advanced Macro with Bob Solow and then, I agreed to become a major, so Charlie is sailing.

The other thing that I always … I actually talked to him about this in the spirit of Manias, Panics and Crashes, I’d become familiar with Frank Knight and the notion of radical uncertainty, Keynes’s Treatise on Probability. We had a discussion one day about when you’re sailing, whatever the meteorologist says, you can go, then you go out and you basically have to keep an eye on things and improvise. You’re not in a structure that … where meteorology or whatever, is strong enough that what’s going to happen. He said to me, “The interesting thing about sailing …” how did he put it? “You can’t get scared and go down below because things will get worse. You have to stay on deck in that uncertainty.” I said to him, “Yeah, that’s like people in a financial crisis, isn’t it? They can’t go run and hide.”

And he laughed, but I remember the sailing analogies being ever present in his teaching and in our conversations, and it’s interesting that you bring that formative experience. So he never really talked to me about his formative experience. He talked about his passion for sailing and for nautical issues, but not the things that you’ve shared with us here today.

Perry Mehrling:

He didn’t talk about himself very much. I mean, I think that was part of his character that he was raised. You’re not meant to be boasty or don’t assume that people are interested in your life. That’s sort of narcissistic … so he restrained that. I think that’s actually one of the reasons his autobiography is not very revealing because I think he … after lifetime of not revealing stuff, he’s not going to change when he’s 80 years old and writing his autobiography. So there’s facts and figures there, but not much of a psychological portrait.

Rob Johnson:

Let’s talk a little bit about this notion of what does finance look like. As an engineer, I could see these models about a terminal condition, optimization, backward induction from the terminal condition, creating the prices and all these things that were even before stochastic, the kind of notion of how dynamic optimization happens. Charlie didn’t seem to embrace the capacity of finance to see into the future, that mighty and uncertainty kind of mindset was there. Many people often compare him with Hyman Minsky, who was another person more in the realm of radical uncertainty. Were they colleagues? Did they work together? Were they kindred spirits in the unfolding of each of their careers?

Perry Mehrling:

Well, I think they were kindred spirits. I mean, I actually have just written a spinoff on exactly this point that will be a paper soon. They were both sort of formed in pre-war … so they shared that sort of American institutionalist sort of upbringing. Hyman was nine years younger than Kindleberger. So the war disrupted his PhD, whereas Charlie finished his PhD before the war, Minsky didn’t until after the war. His supervisor at Harvard was Schumpeter who then died on him. So it was Hansen and others who he ultimately came under the wing. So I don’t think that Charlie knew anything about Minsky, until he started writing Manias, Panics and Crashes. He says himself that he learned about him from … the name is escaping me, the fellow who wrote The Bankers, Martin Mayer, that he mentioned to Martin Mayer that he was writing this thing about … he wanted to write this book about Manias, Panics and Crashes.

Martin Mayer said, “Oh, well, you should have a look at this paper that Minsky wrote.” I think that Charlie had sort of learned in the reception for his first big book, The World in Depression, that people seemed not to get what his argument was there. And I think one reason is that there wasn’t a model. So, he could argue this whole thing until he’s blue in the face, but what economists are looking for is a model. So he thought, why don’t I use Minsky as a sort of vehicle in writing Manias, Panics and Crashes? So he did, and he quotes that one article that Martin Mayor told him about. It’s funny though and that then led to further interaction after that, which I’ll tell you about. It’s sort of in the footnotes in the book, but it’s not pulled together in a whole narrative like I’m doing now.

The article that he hangs everything on, however, is an article that Minsky wrote in 1966 when he was really … hadn’t yet fully formed his own ideas. So the financial instability hypothesis, this idea of hedge speculative Ponzi finance, none of that is in this early article, this early article is attempt to try to get financial instability into a sort of Hansen-Samuelson multiplier accelerator model. So it is a model, but it’s not mature Minsky. It’s Minsky on the way somewhere, and later on, in later editions of Manias, Panics and Crashes, he sort of updates the footnote, but he doesn’t actually update any of the argument. I think that he is not … okay, sometimes people think, “Oh, this is Kindleberger learning from Minsky and extending it to international economics.” I think that’s not really right, that Kindleberger wrote Manias, Panics and Crashes as a work of retirement.

He’s 65 years old. He already has views on international crises that come from his own thinking and transmission internationally and so forth. Remember, Minsky is entirely about domestic, and it’s about business cycles. It’s about the financial forces that are causing business cycles and increasing fragility of business finance, so that a little displacement could … whereas Charlie is about international and it’s about how large events like war and reparations are causing structural displacements that then lead to booms and crashes. So he’s thinking about depression, he’s thinking about war and not about business cycles in the United States. So they became though … I think they realized that they were fellow travelers, and that they were both very critical of the post World War II sort of macro orthodoxy, IS-LM and so forth, including IS-LM-BP, the international extension by Mundell, who was Kindleberger’s student, as a matter of fact.

They were both critical of this and looking for some alternative. So they, I think helped each other in a camaraderie way. I don’t know that Charlie really learned much from Minsky, and I don’t know that Minsky learned much from Charlie, but they were both moving in similar directions for their own interests, and they became friends, and Charlie organized a conference to promote Minsky a little bit and I think they were both also at the Levy Institute that was created. So I think they became friends, but I wouldn’t say that they were collaborators or anything that close. They were both busy with their own agendas, and not to be deflected from their own agendas, but they realized a common spirit.

Rob Johnson:

I think that each was, we might call, revered for not being part of the Orthodox, ego … they may have been in entirely different places, but their similarities, they were both outside the orthodoxy and becoming influential, I think we appreciate it.

Perry Mehrling:

And appreciated both Keynesian and Monetarist Orthodoxy. I mean, they’re both in their politics. They’re sort of more sympathetic with the Keynesians than with the Monetarist. They were not sympathetic with the mechanical version of Keynesianism that became the dominant form in the post World War II period.

Rob Johnson:

Yeah. Yeah. I found it very interesting to be exposed to him at MIT. I think about this because I went on to graduate school at Princeton, which was a very game theoretic and mechanical oriented curriculum, when I got there, people like Lester Chandler, William Baumol were now emeritus. So, I get there and it’s very rigorous and mathematical. There was part of me that was a little bit alienated. I was lucky that Axel Leijonhufvud was at the Institute for Advanced Studies, and he encouraged me. He said, “You’ve done enough math in your undergraduate years, stick with it. You’ll learn and you’ll enjoy and take some history courses,” and meet Albert Hirschman and Marcello De Cecco and other people who were at the institute.

At the same time, when I was an undergraduate, I was aware that in the same quarters when I was working with Edelman and Kindleberger was this brilliant guy named Paul Krugman that everybody really liked. Paul’s emphasis was another form of learning for me, which is the models aren’t necessarily literal truth, but they illuminate, so people can understand the process and the causality that you’re trying to convey. So he felt that which I call, there was an ambiguity or muddiness about a Kindleberger or a Hirschman in not taking the models too literally, but as a parable, you could teach people more easily. I don’t know … Paul then went on and became a journalist and very involved in policy and so forth.

It was a fascinating dynamic, and I guess I want to come as we’re … how we say, thinking about the book in your recent writings. I want to come to the question of Ben Bernanke, who along with my teacher, Phil Dybvig at Princeton and his co-author Diamond just won a Nobel Prize. I know you saw how Kindleberger saw Bernanke. I had met Ben and he had let me read his PhD dissertation long before he was a policy official, even. I think he was at Stanford, he hadn’t come to Princeton yet, but what was going on in the dynamic between Bernanke who seemed to be reaching back to history and maybe a little more institutional texture than a pure modeler like recruitment, but your article illuminated Kindleberger had some concerns about Bernanke’s thinking.

Perry Mehrling:

Well, I think you’re referring to this letter, it’s not actually in the book, this, but when I was in the archives, I found this letter that Charlie had written to Bernanke in 1981 that was … Bernanke was at Stanford and had sent him a draft of this article. It’s the article that’s published in 1983, the one that’s cited in the Nobel Prize. This is 28-year old Bernanke sending to 70 something year old Kindleberger. Here’s something I’ve written that you might be interested in, I ask you for comments. So Charlie gave him comments and he said, “Really, I think number one, you seem not to have read World in Depression. I have a story about what caused that and it’s about credit, but it’s not the credit story that you’re telling and the credit story that you’re telling also is not really right.”

So he walks him through various criticisms of his article, and also Bernanke had sort of dismissed … well, there’s Minsky and there’s Kindleberger who just say that it’s all about irrationality. He says, “No, that’s not in fact at all what we’re saying. They’re dynamics of instability.” So he tried to set young Ben Bernanke on the straight and narrow and had no effect whatsoever. You can see the published article has made no changes. There’s no citation of world and depression, there’s nothing. So Ben Bernanke didn’t know what to make of this. I think, you were mentioning Krugman and about this idea of models, that this is one of the things that we can learn from Kindleberger, right? That if you think that you have translated all of the useful insights of Kindleberger, when you have Diamond-Dybvig model or when you have Ben Bernanke’s credit, you haven’t.

He himself says, you haven’t. So you should still go back. There’s more there. There’s more there. Go back. They’ve found some model that seems to have some aspect, but instead of saying, “Okay, now we can forget about Kindleberger. Let’s build on Diamond-Dybvig, let’s build on this and let’s just create more and more variations of this.” I think there’s actually pay dirt, that graduate students confined in these older techs, inspiration for other kinds of modeling. You mentioned one of these things about finance. The standard sort of simplification in asset pricing is intertemporal general equilibrium, transversality condition. They’re all … where you’re imagining that you have full information out into the future, and that gives you a model.

It gives you something that you can close and you can solve. Okay. It’s not true. It’s not true about the world, and really, everyone knows it’s not true. It’s a story, okay? It’s a story that maybe, we sometimes find a little excessively comforting because the thinking that the world is like that is comforting, but the world is not like that. So if you behave as if the world is like that, it’s going to hand you your hat every now and then. All traders know that these are really just models. That’s not actually how the world works, and you mentioned that Charlie hadn’t really … and neither did Minsky really bring modern finance into their world because they were growing up, important to appreciate, in a time when capital markets were really close down in the Great Depression and in World War II, the capital that flowed internationally, this was government finance.

It was not commercial finance, not a commercial logic, okay? Capital markets recovered really fine in the 60s and so forth. Modern finance sort of got going in the 70s, which is when I said, Charlie’s career is already tailing down. So he’s really much more on the money side of the world, where you’re thinking about payments, you’re thinking about short-term capital flows in order to keep reserves from flowing. So he comes from a money and banking more place and not about asset valuation of stocks and bonds and things like that. So that’s when I said, I can learn from Charlie, but where we need to then build is you have to bring finance much more seriously into this than either Minsky or Kindleberger did. That’s the big thing that got added, really, when they were at the end of their careers.

So that’s my ambition is to move things sort of in that direction, take some of that wisdom that they have and now, look at modern finance. This is why I wrote the earlier book, the Fischer Black and the Revolutionary Idea of Finance is to really get deeply into one of the great minds there so that you can see, “Well what? Okay, now we can think,” remember that Kindleberger and Fischer Black are at MIT at the same time, okay?

Rob Johnson:

I took courses from both of them.

Perry Mehrling:

So there’s some intellectual cross-fertilization somewhere, and maybe just in the minds of their students like you, that you could see there’s something each one of them seems to know about the world that seems right and yet they seem also in contradiction. So how can this be so? Of course, that’s how thought advances. How can this be so? How can this be so? Instead of saying, this one’s right, that one’s wrong, say, “Well, each of us has a little piece of the truth. It’s touching the elephant that we, in trying to figure out what this creature is.” And if you’re just touching the tail, you have no idea. If you’re just touching the tusk, you have no idea. You need to touch it in multiple places to get a picture of this elephant that is the global economy.

Rob Johnson:

What’s funny, when I became an economics major … I had grown up in a very turbulent place called Detroit, Michigan. In my first advanced micro course, I listened to these conversations about equilibrium, and I raised my hand. I wasn’t trying to be a smart ass, but I raised my hand and I said, “You talk about equilibrium, isn’t that like assuming a happy ending?” Not that semester, but the following semester, which I took my first econometrics course, and I remember gentleman … he actually lived for a while in Martha’s Vineyard, his first name was Ed. I’m trying to remember.

Perry Mehrling:

Kuh. Ed Kuh.

Rob Johnson:

Kuh. Ed Kuh. Yeah, and we were in the middle of a section on Fourier transformation, which is something as an electrical engineer, which I became my other major. I was doing a lot of Fourier transformation, and I remember saying to him, “Professor Kuh, I’m having a hard time because when you do a Fourier transformation, laser light laboratory or whatever, it fits exactly. When you do it with time series data and economics, the answer … it just looks like mud. It doesn’t look like …” So there was something about the formalism that I was curious to learn, but I thought it applied very well to engineering or boat design or aerodynamics. I didn’t find it transportable with the same kind of, what you might call quality of result when it came to economics.

Then, meeting Kindleberger who was coming from another direction or meeting Fischer Black, who’s course on options, and so far I took it this Sloan School. I just kind of … how would I say, I didn’t feel like I needed certain answers, but I was skeptical about whether economics could teach me about what happened in growing up in Detroit because it never felt like an equilibrium. It felt like an avalanche.

Perry Mehrling:

I don’t know if you know that I was born in Detroit, but we only lived there a couple of weeks, so I don’t remember any of it. Well, it’s on my birth certificates too. So Charlie viewed … I mean, as an American institutionalist, his image economy is much more biological than engineering, that it’s about institutional evolution. Darwinian, he would say, Darwinian evolution, where there’s challenges, environmental challenges and you’re responding to them, but the environment is changing too. So, this is what we need to appreciate. So when you’re looking at a time series, you’re looking at data that’s been collected over a long period of time when in fact, the beginning data generating process is not the same as the data generating process at the end.

Yes, there’s a GDP in each place, but assuming that these data are being generated by the same process and therefore you can use a transformation, that’s what you’re assuming when you’re doing these Fourier transformations, that there’s an underlying constancy, which he would deny. Of course, he denied that because he grew up in the Depression and World War II. These moments of discontinuity are formative in his idea about how the world works and the transformations after World War II as well. I mean, remember that the European currencies were not convertible until 1958 and then, Nixon takes the US off gold in ‘71. This is a big transformation, and then the Volcker shock of ‘79. It just seems unlikely that the resulting data series is the result of a stationary process.

So you can throw this math at it, but what knowledge are you going to get out of that? Is this really the right method? It depends on what questions you have, of course but for him, I think he sometimes would pretend that he never retooled, when economics moved in this mathematical direction, he never retooled. I think he never retooled because he never saw the reason for it. That he had in 12 years of government service, played a very important role in shaping the post World War II institutional structure and without the help of advanced mathematics and econometrics, and so did everyone else in the New Deal. So he knew that the old ways could work. They could help you.

So, he was never that impressed. In fact, late in life, I quote some of this in the book too, he of course, couldn’t say that so much when he was on the MIT faculty, but later on when he was not on the MIT faculty, he would say things, I use this as an epigram in one of the chapters. The day of positive economics is not yet. We don’t have enough knowledge of how the world works to know that if you change this dial, this thing will happen. We don’t know that. We don’t know that. We know very little about … there are some things maybe that we can build on, but they’re very primitive and they’re very fundamental that you can rely on. That’s how he was thinking in his third career, post retirement. He was quite evangelical about that.

And maybe he encouraged you because you were good at math and he felt that this was … and you could do history too. So, this was not somehow distracting you from learning about the world and maybe some of it would wind up being useful. So he didn’t view this necessarily as the enemy. In that sense, he’s not actively heterodox or something like that, in the way that sort of Minsky kind of became. Why isn’t he? Well, because he’s a central banker, he knows how central bankers think. He knows how the economists of the State Department think. That’s not heterodox. That’s just useful. That’s just useful. So he never felt himself to be … he was an outsider, he was on the fringe of academia, but he never felt himself to be somehow not part of world history.

I think he did feel that he had ancestors and that he would have a legacy also, that would follow after him, despite the fact that he was on the fringe during a certain historical episode. He had that long view, and I think he was right about that, and I told you, he started this by asking, “How did I come to this?” That I wasn’t originally going to do Kindleberger, I was going to do the global dollar. When I found Kindleberger, I found somebody who really helped me do the global dollar. I think he will help the people who read the book too, to understand what are the dynamics that are driving this. That the key currency approach is kind of correct and has been proven by history. So the insistence on sticking with Mundell-Fleming or jazzing it up by now, let’s add another tweak or here, that’s how academia works.

You should look outside the window a little bit and get some historical perspective and appreciate there are other ways of thinking about the world that might give you more … that might get to the core of what’s happening better. Yeah.

Rob Johnson:

Well, I know years later, I saw a report that David Colander and Bob Solow wrote, and they had surveyed economics graduate students about what did you need to know? And basically 90 or 85 to 95% said, you need to know statistics and math and be good at those things. Only 13% said you need to know anything about the institutions of the economy, but-

Perry Mehrling:

I was one of those students. I was at Harvard then, and I took that survey.

Rob Johnson:

Well, I found that fascinating and then, as I moved along when I was in graduate school at Princeton, I went down to Rutgers and Paul Davidson was talking about the lack of ergodic stability, and he was writing a book about Keynes. Then, later on through the economist, Peter Ken and I met Paul Volcker who liked to go fishing. He had a nautical propensity as well, but he really was not at all convinced by which you might call the efficient market source stable, ergodically stable dynamic programming or any of that kind of stuff. I felt like having known Charlie a little bit helped me feel comfortable in getting to know Paul Volcker as you-

Perry Mehrling:

Well, sure. He’s a central banker. He has a central banking kind of view of the world that some bankers know, as Badgett said a long time ago, that money doesn’t manage itself and Lombard Street has a lot of money to manage. That it’s a system that tends to crisis, and so it needs to be watched. That’s something that’s not really in the economic models, but it’s in the world. Central bankers cannot avoid it. That’s in fact, the center of their attention. Charlie had a big lesson in that at the New York Fed and at the BIS, which he never forgot. So he’s a central banking sensibility, I would say and naturally, that would connect with Paul Volcker as well.

Rob Johnson:

Yeah, as you know from the outset that we did a lot of work with the Volcker Alliance and found him very nourishing. I think we draw things to a close here. If the spirit of Charlie Kindleberger were to adjoin us on this cast, what would he say about crypto and what’s happening in the crypto world these days?

Perry Mehrling:

Well, I think he would add a chapter to Manias, Panics and Crashes and put out an eighth edition. In fact, that’s what is happening that Robert McCauley, who was a student of his, is now putting out the eighth edition of Manias, Panics and Crashes. I understand that he is added a chapter on crypto as well. So, that it would be one of those … there’s nothing new under the sun. It’s different technology. It’s different, all of this … the formal structure, but it’s not something we haven’t seen before, and he would analogize to previous crises. So the displacement that God crypto started, I imagine he would talk about the global financial crisis and the response to that, which was zero interest rates in the global North.

So that crypto grew in that kind of unusual experience, but that’s not going to go on forever. Now, we’re in the discipline phase and we’re finding out what was real and what wasn’t, and most of it was not. Bitcoin was supposed to be a kind of digital gold. I remember when students were with this … so this is before FTX and modern stuff, that it’s an asset that’s nobody’s liability and they were an often analogizing to the gold standard. Of course, Charlie knew how the gold standard worked and he would say, “It’s not really right to say that gold was money. Sterling was money.” Okay, and what is sterling? Sterling is a promise to pay gold. Okay. It’s credit. It’s a form of credit. Under the dollar standard, it’s the same. Under Bretton Woods, the dollar was a promise to pay gold. When you took gold out of the picture, it’s still a promise to pay.

So it’s a credit system, really. So Bitcoin is not the notion that … you’re using wrong monetary theory, if you think that Bitcoin is going to challenge the dollar. That’s not going to be right. That’s not going to work, and I told my students that when Bitcoin … I didn’t pay attention to it because of that, because this claim that it was going to replace the dollars seemed to me so obviously false, but it did other things. So they created this little parallel bubble universe. Then, the stable coins came along, which created a bridge between fiat world and crypto world, which really blew things up, which is now collapsing, that we’re seeing. So you’ll see this chapter by Bob McCauley in Manias, Panics and Crashes. I think he is trying to channel Charlie in thinking about this issue.

Rob Johnson:

Excellent. Excellent. Well, thank you for that. Thank you for writing this book. Thank you for all you do for INET. I’m sure they will enjoy hearing your thoughts today in the Young Scholars Initiative and beyond. Perry, you’ve been an enormous contributor to INET and you’ve been an enormously interesting writer about finance throughout your career, and I’m very grateful to know you, and I’m very much admire the work that you do.

Perry Mehrling:

Well, thank you, and thank you for INET’s support. It’s made a big difference these last 10 years. It really has.

Rob Johnson:

Well, you’ve made a big difference, so we got value for money. This isn’t crypto scholarship. This is the real thing. At any rate, let’s adjourn for today. I look forward to the next chapter with you down the road. Maybe we’ll bring on Bob McCauley and do a three-way discussion of-

Perry Mehrling:

Sure. That would be great. That would be great.

Rob Johnson:

The augmented Manias, Panics and Crashes. That’d be fun. Great. Bye-bye for now. Check out more from the Institute for New Economic Thinking at ineteconomics.org.