The system by design constrained financial institutions with significant social welfare reforms and large oligopolistic corporations that financed investment primarily out of retained earnings. Private sector debt was small, but government debt left over from financing the War was large, providing safe assets for households, firms, and banks. The structure of this system was financially robust and unlikely to generate a deep recession. However, the constraints within the system didn’t hold.

The relative stability of the first few decades after WWII encouraged ever-greater risk-taking, and over time the financial system was transformed into our modern overly financialized economy. Today, the dominant financial players are “managed money”—lightly regulated “shadow banks” like pension funds, hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, and university endowments—with huge pools of capital in search of the highest returns. In turn, innovations by financial engineers have encouraged the growth of private debt relative to income and the increased reliance on volatile short-term finance and massive uses of leverage.

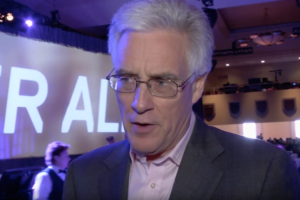

What are the implications of this financialization on the modern global economy? According to Adair Lord Turner, a Senior Fellow at the Institute for New Economic Thinking and a former head of the United Kingdom’s Financial Services Authority, it means that finance has become central to the daily operations of the economic system. More precisely, the private nonfinancial sectors of the economy have become more dependent on the smooth functioning of the financial sector in order to maintain the liquidity and solvency of their balance sheets and to improve and maintain their economic welfare. For example, households have increased their use of debt to fund education, healthcare, housing, transportation, and leisure. And at the same time, they have become more dependent on interest, dividends, and capital gains as a means to maintain and improve their standard of living.

Another major consequence of financialized economies is that they typically generate repeated financial bubbles and major debt overhangs, the aftermath of which tends to exacerbate inequality and retard economic growth. Booms turn to busts, distressed sellers sell their assets to the beneficiaries of the previous bubble, and income inequality expands.

In the view of Lord Turner, we have yet to come up with a sufficiently robust policy response to deal with the consequences of our new “money manager capitalism.” The upshot likely will be years more of economic stagnation and deteriorating living standards for many people around the world.