It’s time for business executives, employees, and taxpayers to come together to help get us out of the pandemic and create conditions for a sustainable and equitable future

Here are the key ways to respond to the coronavirus crisis and prepare for the future.

1. Mobilize American workers for productive employment

With no end in sight to the social distancing that is essential to containing the spread of covid-19, the U.S. economy is in imminent danger of collapse. We’ve seen this movie before, in 2008-2009, when the federal government bailed out Wall Street and the auto industry. But given the scale and scope of the pandemic crisis, that “inside job” will look like the short film before the main feature that is being scripted before our very eyes. Businesses, from hairdressers to airlines, will need government assistance if they are going to keep workers employed and stay afloat. As we, the people, watch this epic unfold, those government policymakers whom we can trust need to be laser-focused on both the objectives of government support for business and the forms that government support should take.

The objective of government support for business must be, first and foremost, to keep people employed. A vicious cycle of layoffs and small-business closures will transform a sharp recession into a deep depression. With physical mobility restricted, however, policies that ensure that as many people as possible continue to receive paychecks is not enough. Every business that keeps its workers on the payroll will face challenges to keep them not only safely employed but also productively employed.

With increasing numbers of people working from home, companies may have to invest in the equipment required for remote work if households do not already have access to the requisite communication facilities. Insofar as employees cannot perform their usual tasks remotely, companies will have to retrain them in other types of work that they can do from home. Much of the new work that businesses can do will be on contract to government agencies, supplying goods and services needed to fight through the pandemic, keep people healthy, maintain as much productive activity as possible during the crisis, and set the stage for economic recovery.

We are engaged in a war against the pandemic, and both government agencies and business firms must view the mass mobilization of the labor force in productive employment as vital to maintaining the viability of the economy and the integrity of civil society. Leadership in this business-government collaboration is of the essence. Responsible government officials, business executives, union leaders, community organizers, and social activists need to join what must be nothing short of a wartime effort to keep people productively employed.

At the same time, Americans need to be aware of the predatory value extraction that over the past decades, and particularly since the financial crisis of 2008-2009, has concentrated income among the richest households. What amounts to the looting of America’s large corporations has eroded employment opportunity and foisted economic insecurity on most U.S. households, making them more vulnerable, medically as well as financially, to the current crisis. In particular, for reasons we have spelled out elsewhere and which we outline below, we call for an immediate ban, right now and forever, on stock buybacks done as open-market repurchases.

That should be easy. Back in November 1982 the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) gave corporate executives permission to loot business corporations by adopting a single, misguided rule: Rule 10b-18. Since the mid-1980s senior executives of publicly listed corporations have executed trillions of dollars of buybacks, the sole purpose of which is to manipulate their companies’ stock prices.

As it is, in 2016 the wealthiest 10% of U.S. households possessed 84% of the value of U.S. publicly traded corporate shares. Buybacks enrich an even smaller group of the richest people who are in the business of timing the sale of shares. Specifically, buybacks have overwhelmingly benefited a small number of stock-market traders, including senior corporate executives themselves and corporate raiders (aka “hedge-fund activists”), while leaving most Americans worse off. Rescind Rule 10b-18, and these types of stock buybacks would become prosecutable for insider trading and as stock-market manipulation.

We also need to be alert to the predatory practices of hedge-fund activists such as Carl Icahn, Nelson Peltz, and Paul Singer, who have become billionaires by looting the U.S. business corporation by a method that Rule 10b-18 has, in essence, legalized. These corporate raiders are right now mobilizing their vast “war chests” to acquire the shares of major, publicly listed corporations at pandemic-level prices. In seeking to drive up stock prices and reap financial gains, these raiders will find, or install, collaborators among the corporate executives and board members of their target companies. Together, these predatory value extractors will enrich themselves by downsizing their companies’ labor forces and distributing corporate cash to shareholders.

This corporate devotion to a strategy that we call “downsize-and-distribute” will accelerate the descent of the U.S. economy from recession into depression. What we need to survive the pandemic is, to the contrary, a regimen of “retain-and-reinvest”: corporations need to retain every cent that they possess and reinvest in the productive capabilities of their workers with a view to keeping them productively employed.

2. Insist on conditions for government assistance to big business

The leaders of every business in the nation, large and small, should be thinking about ways to enable their employees to continue to make productive contributions during the crisis. Government agencies should provide assistance to business enterprises that are committed to the effort to keeping as many people as possible productively employed. That will ease the burden on the government in providing extended unemployment benefits, healthcare, and cash grants to those households for whom employment income is not available or possible.

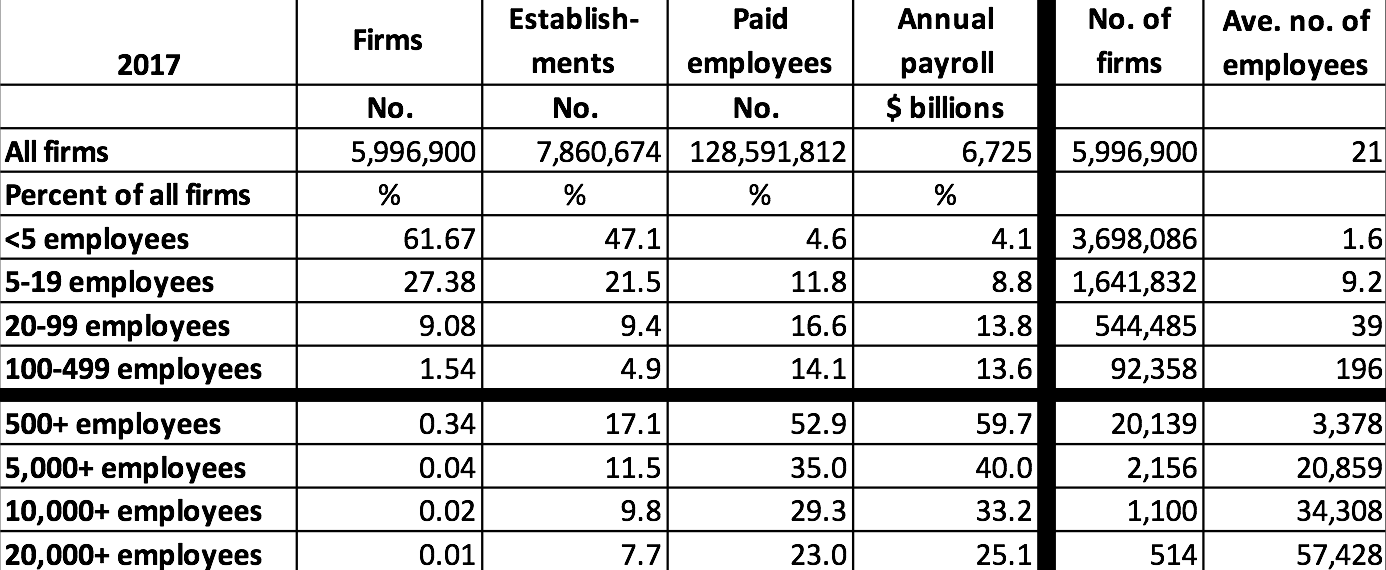

The assistance programs to business cannot be one-size-fits-all because, as shown in Table 1, the size distribution of businesses in the U.S. is extreme. Of almost six million firms in the U.S. in 2017 (the most recent data available), 62% employed fewer than five people, with an average of 1.6 employees per firm and 4.6% of all business-sector employees. At the other extreme, 514 firms with 20,000 or more employees, and an average of 57,428 people per firm, employed just over 25% of all business-sector employees and accounted for an estimated 29% of all corporate revenues.

Table 1. Employment of the U.S. business-sector labor force by size of firm, 2017 Source: United States Census Bureau,”2017 SUSB Annual Data by Establishment Industry,” March 2020, at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/susb/data/tables.html

It is imperative that government’s financial support be conditioned on a corporation’s commitment to keeping its labor force productively employed. The biggest businesses will pose the greatest challenges when it comes to setting conditions for support because of both their political influence and their importance to the economy. Certainly, the U.S. companies with 20,000 or more employees should be presumed to be too big to fail, although in each case the characteristics of the particular industry supply chains and local business ecosystems need to be taken into account in the provision of government support.

With the paramount objective of keeping the labor force productively employed, the government should refuse to provide support to businesses that engage in activities that undermine investment in productive capabilities. In this regard, no single business practice is more pernicious than open-market repurchases, aka stock buybacks. From 2009 through 2018, 465 of the companies in the S&P 500 Index in January 2019 expended $4.3 trillion dollars on stock buybacks, equal to 52% of their combined profits. That was on top of the $3.3 trillion (29% of profits) in dividends that these companies distributed to shareholders. From the fourth quarter of 2018 through the third quarter of 2019 alone, companies in the S&P 500 Index allocated $770 billion to buybacks and $477 billion to dividends.

Indeed, many companies have borrowed to do buybacks, a move that, even when they made it, clearly increased their financial fragility in the event of an economic downturn. When profits were plentiful, this profligate financial behavior undermined corporate investment in productive capabilities, especially those of the labor force. Those corporations that are seeing profits vanish in the current crisis were placing their very existence, and their employees’ jobs, in great peril through their financialized behavior.

In going to Congress to request financial assistance, the senior executives and board members of these corporations need to vow that their companies will never, ever, do buybacks again. If the incumbent corporate executives and directors can’t shed their addiction to buybacks, then they should resign their positions and make way for corporate leaders who can. And, if they simply do not understand why buybacks are bad for our wealth and our health, we are here to explain why.

3. Face the damage that stock buybacks do

Stock buybacks do damage because the profits (i.e., earnings or net income) that a business retains form the financial foundation for corporate investment in the productive capabilities that can generate competitive products. A company that retains corporate profits and reinvests in productive capabilities can provide employees with higher pay, more employment security, and superior career opportunities compared with a company that downsizes the labor force by laying off workers and squeezing wages, and that distributes corporate cash as buybacks and dividends. In the subtitle to his 2014 Harvard Business Review article, “Profits Without Prosperity,” William Lazonick summed it up thus: “stock buybacks manipulate the market and leave most Americans worse off.”

A company can also reduce the profits available for investment in productive capabilities by indulging in high dividend-payout ratios. But the damage from buybacks runs deeper. While dividends are paid out to shareholders for, as the name says, holding shares in the company, stock buybacks reward sharesellers who are in the business of timing the buying and selling of shares. In the vast majority of instances, the sole purpose of a stock buyback is to give a manipulative boost to the company’s stock price. As detailed in the book Predatory Value Extraction, the prime beneficiaries of stock buybacks are senior executives of major corporations, with their remuneration dominated by manipulation-enhanced stock-based pay, and hedge-fund managers, for whom timing the movement of stock-market prices is a central element of a parasitical modus operandi that can yield among the highest incomes in the land.

Damage is done by buybacks even when they do not immediately deplete the corporate cash available for investment in productive capabilities. A large majority of buybacks are done in booms, when profits are plentiful, and corporations are competing to increase their stock prices. Moreover, the lion’s share of buybacks is done by the most profitable companies, which are able to distribute massive amounts of cash to sharesellers and shareholders without facing liquidity constraints. The problem is that, as they concentrate on buybacks, the senior executives who control strategic decision-making in these companies lose the incentives, and often also the abilities (if they had them to begin with), to make investments in innovation that can build on the company’s existing capabilities.

Take, for example, the case of Apple, one the most successful companies ever. From October 2013 through the December 2019, CEO Tim Cook and his board dissipated $326 billion on buybacks (82% of profits) while paying $92 billion in dividends (another 23% of profits). Yet, given the continued popularity and premium pricing of its iPhone (notwithstanding a declining market share), on December 28, 2019, Apple still had $42 billion in liquid assets on hand.

The damage wrought by Apple’s buybacks, therefore, has not been manifested in the company having faced financial constraints on investment in productive capabilities. Rather, the problem is one of strategic management. With his attention focused on doing buybacks to boost the company’s stock price, CEO Tim Cook has eschewed making innovative investments in the technologies of the future in areas such communications, energy, and healthcare. Such investments could have built on the formidable productive capabilities that had underpinned Apple’s success with the iPhone. Yet with Cook and his board opting instead for predatory value extraction, Apple has suffered an organizational failure that constitutes an irretrievable loss for both the company and the country.

The ideology that legitimizes Apple’s cash distributions is rooted in the deeply flawed argument that, for the sake of economic efficiency, a company should be run to “maximize shareholder value.” In line with this ideology, Apple does its unprecedented cash distributions under its “Capital Return Program.” That’s a misnomer on two counts. First, in doing buybacks and paying dividends, Apple has been distributing cash, not “capital.” When a company invests in productive capabilities, it is investing in human capital and physical capital for the sake of generating commercial products. As financial flows, buybacks and dividends entail no capital investment. The recipient might, for example, use the funds to bid up the price of a Park Avenue penthouse. Second, one must ask to whom Apple is “returning” this cash. In its history, the only funds that Apple has ever raised from the public stock market were $97 million brought by its initial public offering in 1980. Its current shareholders have merely purchased shares outstanding on the market. They are not “investors” in Apple as a productive enterprise. How, therefore, can Apple “return” cash to them?

When, for example, Carl Icahn bought $3.6 billion in Apple shares on the market in 2013, Apple as a productive enterprise did not receive one cent of that money. To the contrary, egged on by Icahn, in 2014 and 2015 Apple did over $80 billion in buybacks (a two-year record at the time, which Apple has since surpassed), helping this parasite take $2 billion in gains when he cashed out of Apple shares in the winter of 2016. Those gains then could be added to what Icahn has long called his “war chest”: funds he has available to engage in further predatory value extraction. It is beyond ludicrous for Apple to claim that it is “returning” cash to Icahn or to any other stock trader who simply buys and sells shares on the market. (Perhaps like Rick Blaine, who came to Casablanca “for the waters,” whoever it was that chose the “Capital Return” name for Apple’s buyback-and-dividend program was misinformed. Now they know.)

The case of Icahn and Apple is not an isolated example. Since 2003 SEC-sanctioned changes in the proxy-voting system, documented in Predatory Value Extraction, have made it possible for hedge-fund activists to rip tens of billions of dollars out of corporations while holding just a small fraction of the shares outstanding. In some cases, this predation has driven a major company to hit a financial wall.

Look at what happened, for example, to General Electric, a company that has been listed on the New York Stock Exchange since 1892. Under CEOs Jack Welch (1981-2001) and Jeffrey Immelt (2001-2017), GE was not at all shy about doing billions of dollars in buybacks on top of the ample dividends on which its shareholders could depend. In 2001-2007, GE spent $61 billion on dividends and $43 billion on buybacks for a combined 87% of profits, before being forced, for the very first time in its long history, to cut its dividend in 2008. In an effort to protect its coveted AAA bond rating, GE also issued shares in the fourth quarter of 2008 at two-thirds of the price for which it had bought the shares earlier that year. In March 2009 Standard and Poor’s downgraded its bond rating nevertheless. That experience did not, however, deter CEO Immelt from doing over $5 billion in buybacks in 2012 and double that amount in 2013. In 2015, GE suffered a loss of over $6 billion.

In October 2015 corporate raider Nelson Peltz and his hedge fund Trian Partners, fresh off an attack that enabled them to effectively control the chemical company DuPont while holding about 2% of its shares, plunked down $2.5 billion to buy 0.8% of GE’s shares outstanding. CEO Immelt proclaimed: “Trian has a strong track record of working with companies to build long-term shareholder value and has been an engaged shareholder.” In 2016, GE returned to profitability, with net income of $8.2 billion, but under pressure from Peltz and with the compliance of Immelt, GE paid out $8.5 billion in dividends in that year while also doing $22.0 billion in buybacks.

Even then Peltz continued to insist that GE downsize and distribute, and in the first half of 2017 the company did another $3.3 billion in buybacks. As the company’s finances weakened, Immelt stepped down as CEO in August 2017 and as board chairman in October, at which point a Trian partner was installed on the GE board. In November 2017, however, GE had to cut its dividend for the second time in its history. The company lost $8.5 in 2017, $22.4 billion in 2018, and $5.0 billion in 2019, and one of the world’s most important and longstanding technology companies had become a shadow of its former self.

And that was before anyone had ever heard of Covid-19.

Then there is the tragic case of Boeing, with the two crashes of its new 737 MAX planes in October 2018 and March 2019 that left 346 people dead. The problem is that, despite a well-known structural design limitation in the 737 series as larger, more fuel-efficient engines powered the planes, Boeing’s senior executives decided to develop, sell, and deliver an unsafe aircraft. The company could have taken a different path if, from the mid-2000s, it had carried out an earlier plan to go back to the drawing board and build a “clean-sheet replacement” for the 737 rather than simply putting a new engine on an existing aircraft architecture. The extra cost of a clean-sheet replacement was estimated at $7 billion, significantly less than the $11 billion that the company spent on stock buybacks from 2004 through 2008. Boeing launched the “re-engined” 737 as the MAX in August 2011.

With 2,500 737 MAX orders in hand at the beginning of 2013, Boeing went on a buyback spree that reached a total of $43 billion in the first week of March 2019—just before the second crash, in Ethiopia. The 737 MAX has been grounded worldwide ever since. From 2018 to 2019, Boeing‘s revenues fell from $101.1 billion to $76.6 billion, its before-tax net income from $11.6 billion to minus-$2.3 billion, and its after-tax net income from $10.5 billion to minus-$636 million.

And that, too, was before anyone had ever heard of covid-19.

4. To avoid a depression, pursue stable and equitable economic growth

GE, with its 70,000 employees in the U.S., and Boeing, with its 161,000 employees worldwide, are among the large firms that, through their pursuit of “maximizing shareholder value” in normal times, have arrived at the pandemic crisis as already-fragile companies that are too big to fail. Expect these two to be among the very large companies that join the queue for a federal-government bailout.

On March 16, the major passenger and cargo airlines, represented by the trade organization Airlines for America, became the first industry group to announce that it would seek government financial assistance as a result of the crisis. Their ask is for $29 billion in grants, $29 billion in loans, and an unspecified amount of tax relief.

The appearance of the airlines’ document outlining its request for assistance resulted in an almost immediate chorus of protests from prominent figures, who noted that the airlines had put themselves in this precarious position by doing tens of billions of dollars in stock buybacks in recent years, when times were good.

Business billionaire Mark Cuban told CNN and CNBC that, for any company that receives federal assistance, the rule should be: “No buybacks. Not now. Not a year from now. Not 20 years from now. Not ever. Because effectively you’re spending taxpayer money to buy back stock and to me that’s just the wrong way to do that.” Cuban went on: “Whatever we do in a bailout, make sure that every worker is compensated and treated equally—in that the executives don’t get rewarded extra to stick around because they got nowhere else to go.”

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer went on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe” to find that the host, Joe Scarborough, was already railing against buybacks. Schumer said: “Our motto in this is ‘workers first.’ The bailout in 2008 helped people at the top. It didn’t help average folks. That is not going to happen on our watch….We don’t want to give [the airlines] money unless they keep all their employees, and they don’t cut the salaries of their employees….And those buybacks: they infuriate me. We should not be allowing them to do buybacks, raise corporate salaries…”

Senator Elizabeth Warren has called for the following “priorities and requirements to be included in any bailout package for big business.” As stated in her press release:

· Companies must maintain their payrolls and use funds to keep people working or on payroll.

· Companies must provide a $15 minimum wage as quickly as practicable but no later than one year [after] the national emergency declaration [ends].

· Companies are permanently prohibited from engaging in share repurchases.

· Companies are prohibited from paying out dividends or executive bonuses while they are receiving any relief and for three years thereafter.

· Companies must set aside at least one seat—but potentially two or more, as the amount of relief increases—on the board of directors for representatives elected by workers.

· Collective bargaining agreements should remain in place and should not be reopened or renegotiated pursuant to this relief program.

· Corporations must obtain shareholder and board approval for all political expenditures.

· CEOs must be required to personally certify a company is [in] compliance and face criminal penalties for violating these certifications.

With support from the Airline Pilots Association, Association of Flight Attendants-CWA, and Transportation Workers Union, Senator Tammy Baldwin reintroduced her Reward Work Act to apply specifically to publicly listed companies receiving federal-government support. They would be banned from doing buybacks forever and would have to agree that one-third of their corporate board members be workers’ representatives. As she put it: “I want to make sure that taxpayers aren’t bailing out big corporations who will just turn around and spend it on stock buybacks that primarily benefit C-suite executives and wealthy shareholders. This legislation will ensure that this economic stimulus supports the workers and small businesses who need it, not the top 1%.”

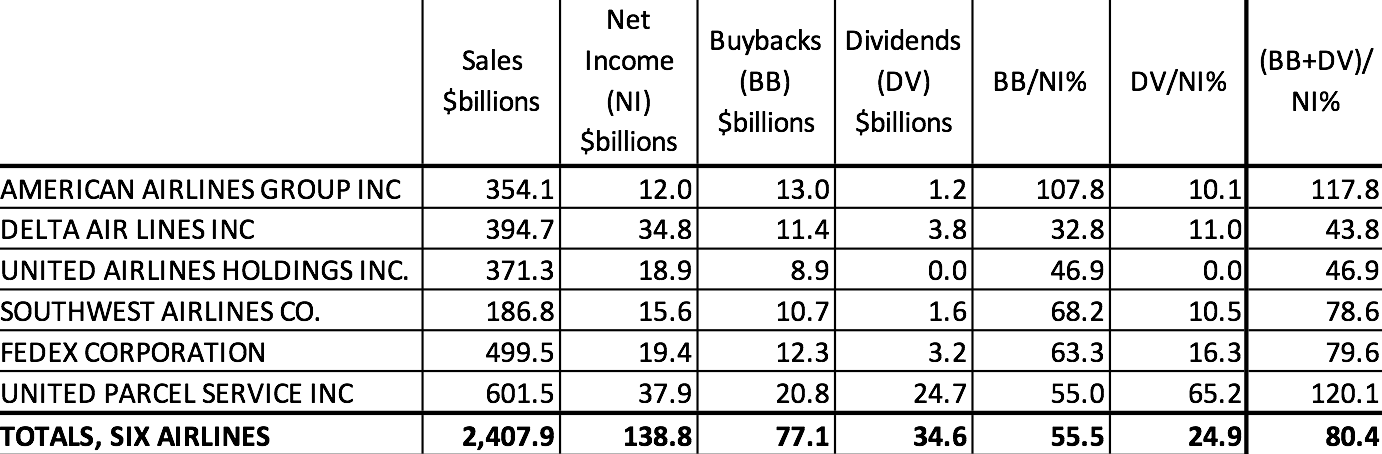

Table 2 provides the numbers on stock buybacks for the four largest passenger airlines (American, Delta, United, and Southwest) and two largest cargo airlines (Fedex and UPS). As of December 31, 2019, American had 131,700 people on its payroll, Delta 91,000, United 96,000, Southwest 60,800, Fedex 450,000, and United Parcel Service 495,000. Over the decade 2010-2019, these six airline companies combined to distribute just over 80% of their profits to sharesellers and shareholders in the form of buybacks (56%) and dividends (25%). At these six airlines alone, buybacks over the past decade were $77 billion, with 71% of them done in 2015-2019. With Delta’s soaring profits, its buybacks might have been even higher in recent years but for the scrutiny of this odious practice by some of its veteran pilots who had lost much of their pensions when the company went bankrupt in 2005.

As we have argued, the sole purpose of almost all stock buybacks done as open-market repurchases has been to manipulate the company’s stock price—a legalized looting of these business corporations. In 2018, in the immediate aftermath of the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, U.S. households as taxpayers already gave companies in the S&P 500 Index about $92 billion in tax cuts that went to buybacks. Now that they have all but eliminated their reserve funds, the airline executives are queueing up, MAGA hats in hand, to fleece U.S. households even more.

Table 2. Sales, net income, buybacks, and dividends at the four largest U.S. passenger airlines and two largest U.S. cargo airlines, 2010-2019 Sources: S&P Compustat database and SEC 10-K filings

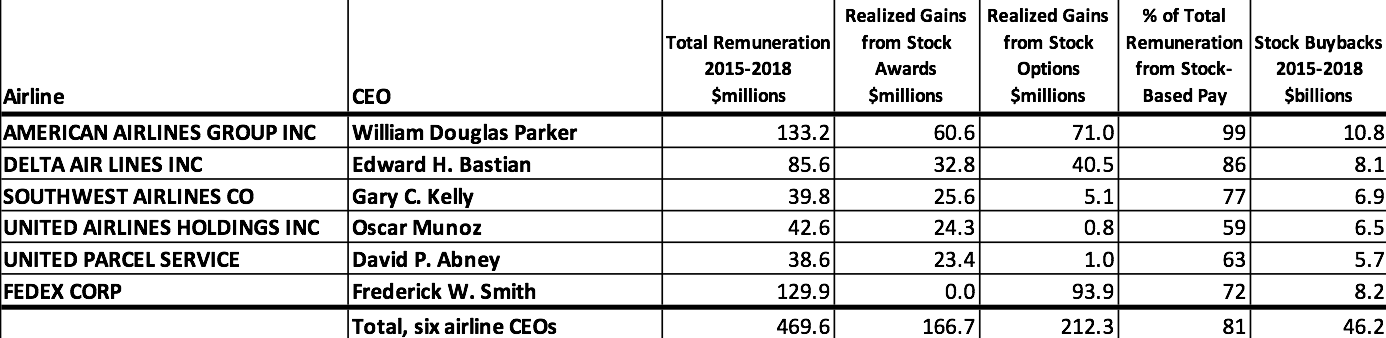

Notwithstanding the stock market crash, the senior executives of these companies will have no problem riding out the economic devastation that, along with the majority of Americans, their companies’ employees may suffer in the months, and perhaps even years, ahead. Table 3 shows the total remuneration that the current CEOs of the six airline companies took home over four years, 2015-2018. These six CEOs averaged $19.6 million per year, with 81% of their money-in-the-bank coming from the realized gains from the exercise of stock options and the vesting of stock awards. The $46 billion in buybacks that they ordered in these four years helped to inflate their already outsized pay.

Table 3. Total remuneration and stock-based pay at the four largest U.S. passenger airlines and two largest U.S. cargo airlines, 2015-2018 Sources: S&P ExecuComp database and company proxy statements Note: For Edward Bastien and Oscar Munoz, the remuneration received in 2015 included non-CEO pay

On March 21, Airlines for America sent its formal request for assistance to the majority and minority leaders of the House and Senate. A4A now specifies that the airlines would use $29 billion in grants to keep 750,000 people employed through August 31, 2020; and $29 billion in loans for unspecified purposes, but with commitments to “placing limits on executive compensation” as well as eliminating buybacks and dividends over the life of the loans.

It is our position that:

a) all federal funds that respond to the A4A request should be in the form of loans, with the U.S. government as senior creditor;

b) all of the loans should be used to keep airline employees not only paid, but also productively employed;

c) the timeframe for this commitment for keeping workers on the payroll should be far longer than August 31, 2020, given that $58 billion in loans amounts to over $77,000 per employee of the members of A4A, which for just five months implies an annual wage per employee of $186,000;

d) senior executives should be incentivized and rewarded for keeping workers productively employed (and if the people currently at the top do not have the capacity to perform this function, they should make way for people who do);

e) the companies must commit to never again doing stock buybacks (the CEOs could reinforce this commitment by calling for the rescission of SEC Rule 10b-18);

f) the companies must commit to paying no dividends in any quarters in which layoffs or wage cuts are occurring;

g) the companies must place representatives of employees and the nation’s taxpayers on corporate boards; and

h) senior executives must pledge that their companies will become advocates of paying their fair share of corporate taxes.

We are all in an unprecedented crisis. It is time for those who control and govern major business corporations to cease being the problem and join with their workers and the nation’s taxpayers to become central to the solution. U.S. business corporations can and should be run for the sake of contributing to stable and equitable economic growth.

The Academic-Industry Research Network is a 501(c)(3) non-profit research organization, registered in Massachusetts. For communications, contact William Lazonick at [email protected].