Evidence emerged last week of a drug that can help improve outcomes for some patients with severe Covid-19 infections. A stock market rally confirmed that this was good news. In similarly certified good news, the Federal Reserve System continued to operate about a dozen ad hoc credit facilities, most of which are newly authorized by the CARES Act of 2020.

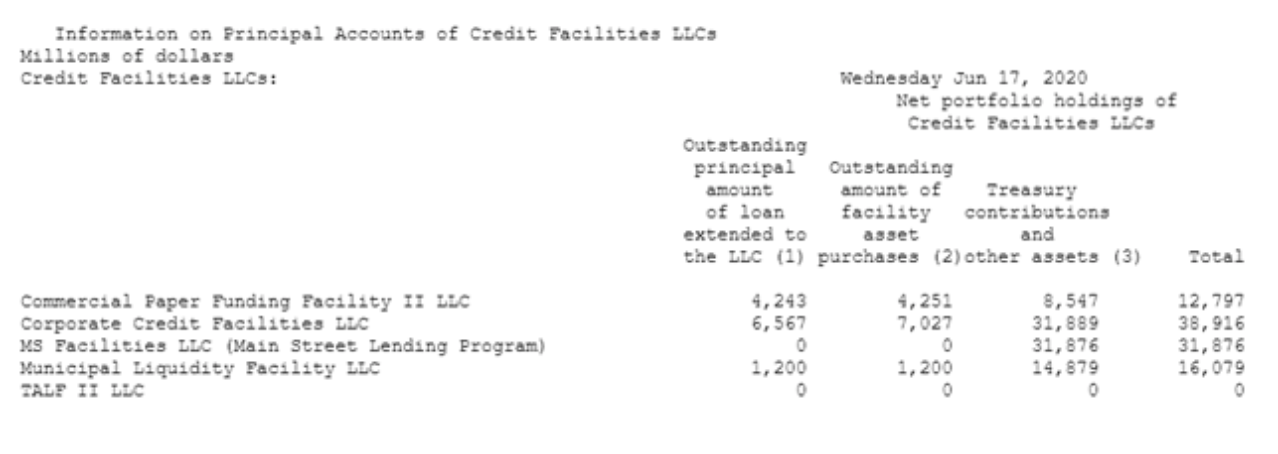

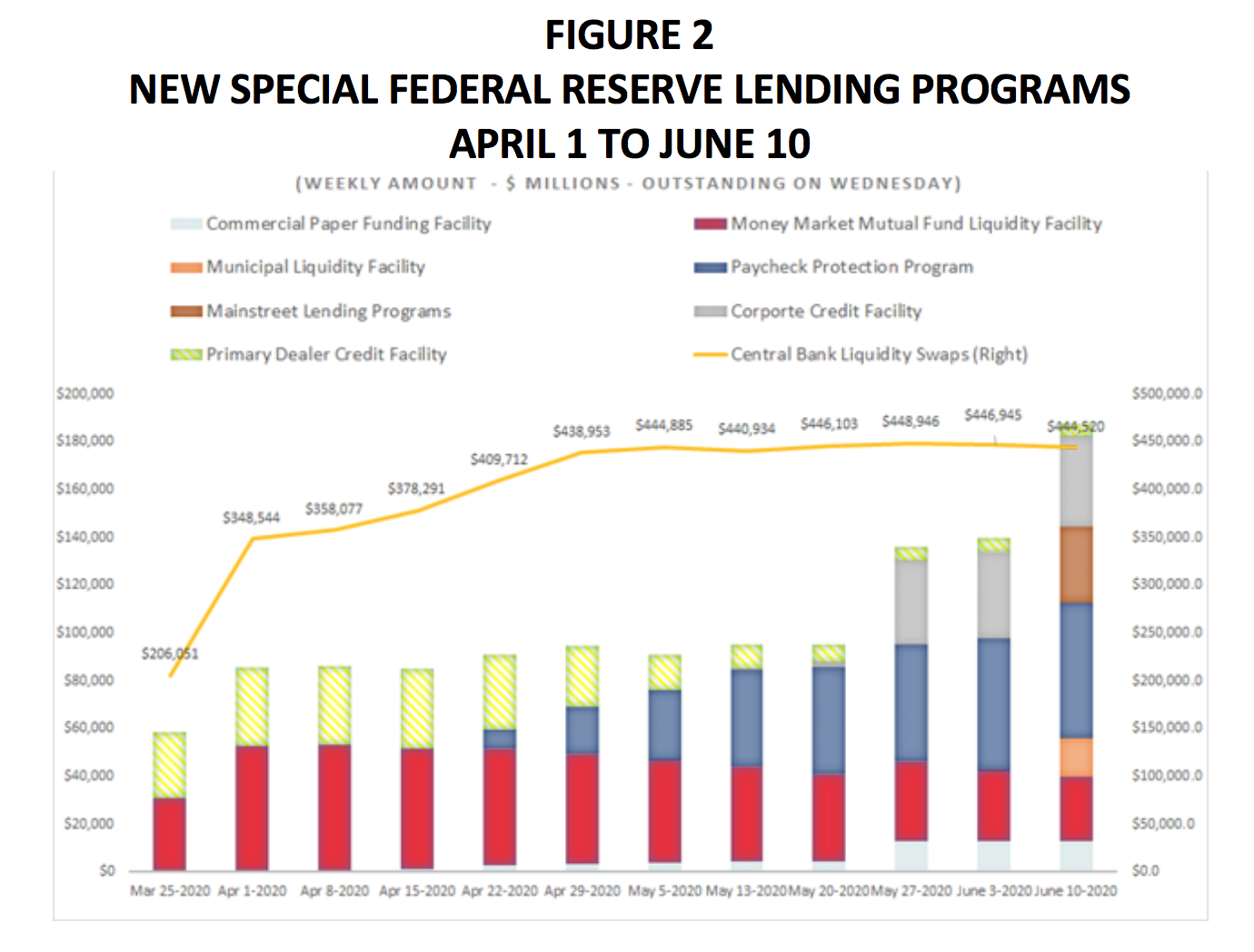

Figure 1 names and Figure 2 plots activity levels, week by week, in eight of the Fed’s operative programs as they have come on line. Who is eligible for these programs and on what terms remains a fluid issue. Still, the stock market seems pleased not only with the programs, but with how the Fed has broadened access to these programs on the fly.

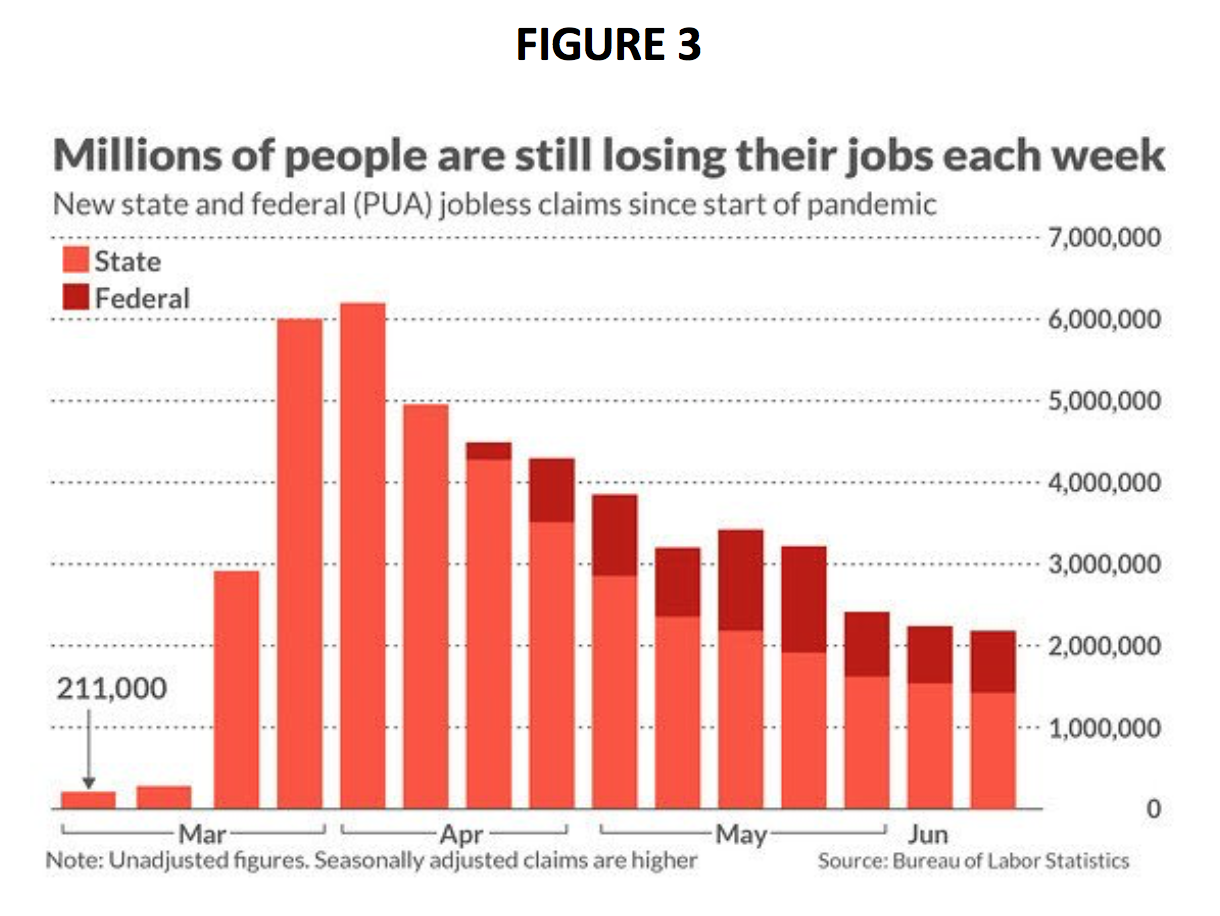

In the face of the unprecedented surge in unemployment shown in Figure 3, Federal Reserve officials have earned points for stepping forward as perhaps the government’s premier and most agile economic firefighters. Using their limited policy toolkit, they have enhanced the flow of credit and liquidity to some of the markets and borrowers that figured to be greatly impacted by the unfolding economic catastrophe. And they did this at a time when Congress and the Executive branches of the federal government took a few weeks to figure out how to channel taxpayer subsidies to lucky firms through the Treasury and the Fed.

But no matter how well-intended ad hoc credit programs may seem at their start, history tells us that efforts at government credit allocation tend to unravel as time goes on. Although one could cite example after example of this deterioration, it should be enough to point to the repeated hash that has been made of programs aimed at subsidizing homeownership. The successive failure of housing-finance programs is rooted in the incentive conflicts that develop on both sides of any subsidy scheme. On the supply side, it becomes more and more difficult to monitor and restrain the ways in which agency personnel respond to industry and Congressional pressure to expand subsidies. On the demand side, participants learn to exploit two ways to increase their access to subsidies. First, they learn how and how far they can influence individual regulators on different issues. Second, they learn ways to make sure that the benefits that captured regulators and legislators deliver far exceed the costs of building and exercising the necessary clout. The steady rollback of Dodd-Frank reforms over the last decade vividly illustrates the workings of this inch-by-inch process. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3593916

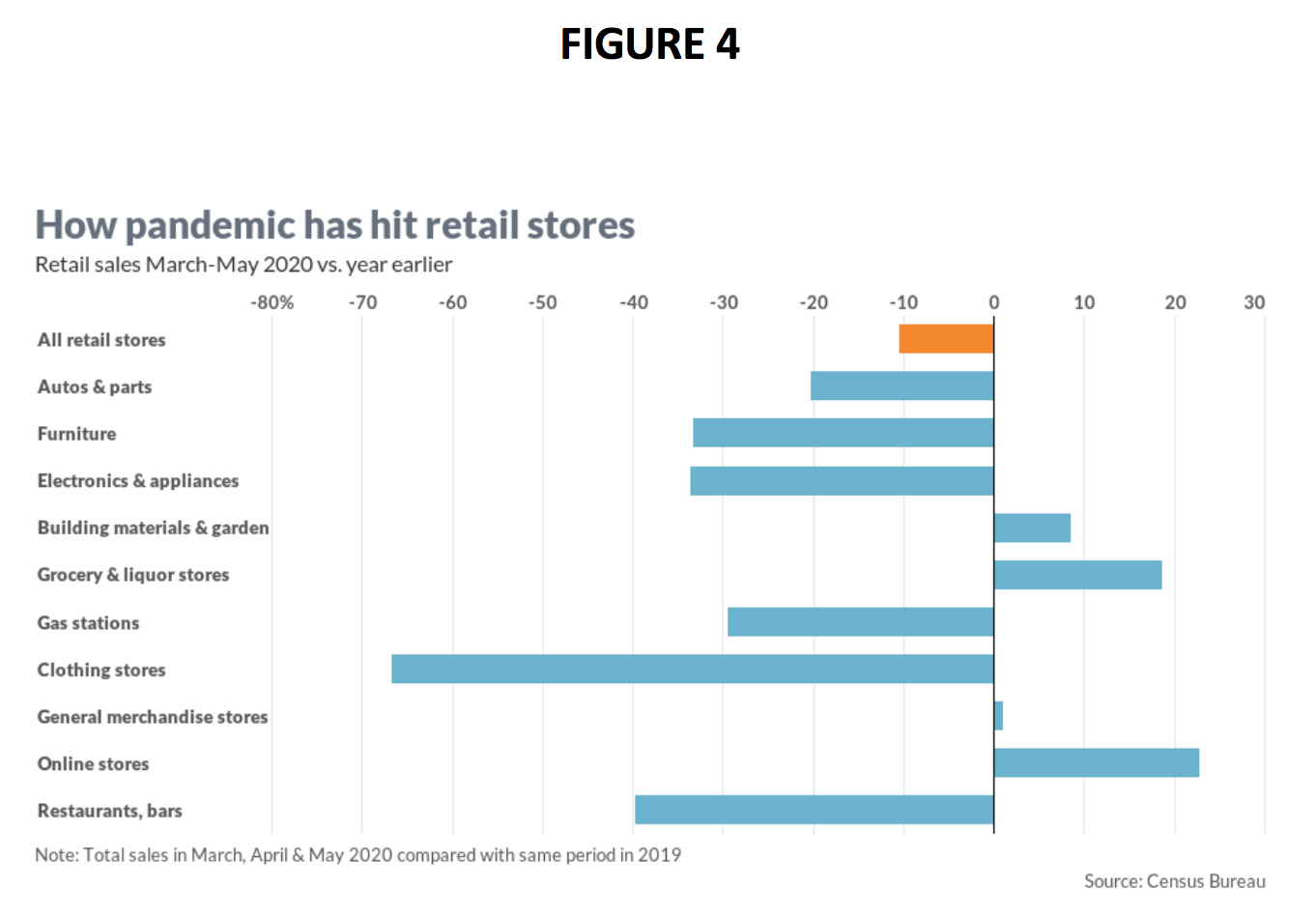

At the moment, it is easy to ignore this and other subtle elements of what is bad news for the longer run. For example, no one wants to hear each day that the number of infections and deaths in the US continues to lead the world. States such as Florida and Arizona whose governors prematurely reopened their economies are setting records for new infections every day. Second, statistics on retail sales (shown in Figure 4) show us how citizens are responding to the social-distancing movement. They tell us that many citizens are drinking more, eating at home more, and doing more of their purchasing online.

When the pandemic is over, our country’s industrial geography is going to look considerably different than it did a year ago. Workers and capital equipment will find themselves in new locations and exercising new functions. Firms that need to monitor worker input as well as worker output or that need to staff a production line will bring a good part of their labor force back on board. But it should be clear that, in many endeavors, firms and their employees have found definite advantages in allowing some categories of employees to work online from home on at least a part-time basis.

Firm by firm, managers should be trying to identify the activities in which the benefits of keeping workers onsite cannot cover the cost of hardening the safety of the workspace where they operated before the pandemic. Wherever net benefits seem negative, the space should quickly be offered for sale, leasing or sublease.

For example, suppose that one-third of work that had traditionally entailed face-to-face meetings turns out to be more efficiently performed online than in person. This would mean a massive reduction in the need for daily commuting, cross-country travel, and office space in center cities.

Moving to a new equilibrium requires not only the exit and repurposing of resources currently used in the oil, travel, and hospitality industries, but a fall in the rents that can be earned on commercial and residential property of all sorts. We say this for two reasons. First, cheaper property distant from city centers will become more attractive to households and businesses that no longer need to be near city centers. Second, converting commercial real estate to new uses in the city center will reconfigure rents and house prices across what will be an expanding metropolitan area.

Congress and the Federal Reserve have focused on preparing programs of relief for firms in the most deeply damaged industries, but forbearance is not forgiveness. Everybody cannot subsidize everybody at the same time. Nor can the intergenerational costs of the interventions officials decide upon now be shifted forward forever.

What worries us particularly is the lack of planning for ways to exit and otherwise rationalize the Fed’s credit-allocation programs so as to speed the transition to a viable new equilibrium. It is clear that, the longer it takes to develop and distribute effective vaccines and cures, the larger the mountain of unpaid credit-card debt, rents, mortgage payments and other bills that will emerge. For example, the current partial moratorium on foreclosures and evictions is a policy whose long-run effect is a growing backlog of worried households, landlords, and mortgage investors whose unpaid claims will have to be settled eventually. What is missing from the federal government’s rescue program is an effort to speed up the process of rent and occupancy adjustment.

Everyone knows, for example, that processes of foreclosure, eviction, and re-leasing properties to new tenants will generate huge transition costs. To minimize these costs, we need policies that invest in keeping people and resources in place wherever and whenever this is efficient. It can’t be efficient to close popular restaurants only to reopen them with more or less the same cuisine under a different name and with a new staff. Nor does it make sense to empty apartment buildings on a wholesale basis and refill them with displaced tenants from a few blocks away.

We are reminded of the commonsense advice that no one can get blood from a turnip. If the concept of a “justice” system is to mean anything, efficient tools for breaking leases and distributing opportunity-cost losses between tenants and landlords and between lenders and borrowers must be expanded with the goal of resetting the terms of what has become an economy-wide network of unenforceable contracts.

It seems clear that governments should be looking for ways to expand, redesign, and repurpose their bankruptcy, small claims and rent courts. We can’t leave everything to the Federal Reserve. Programs should be underway in law schools and at every level of government to design and to staff a virus-driven system for identifying and realistically re-setting the terms of what have become unfulfillable contract obligations.

Figure 1

Names of Crisis-Driven Programs Assigned to the Fed

Primary Dealer Credit Facility PDCF

Term Asset-Back Securities Loan Facility TALF

Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility MMLF

Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility PPPLF

Primary Money Market Facility PMCCF

Secondary Market Commercial Credit Facility SMCCF

Commercial Paper Funding Facility CPFF

Main Street New Loan Facility MSNLF

Main Street Priority Loan Facility MSPLF

Main Street Expanded Loan Facility MSELF

Municipal Liquidity Facility MLF

Central Bank Liquidity Swaps CBLS

Source: Compiled by Robert A. Eisenbeis from the Davis Polk website

Source: The Federal Reserve’s H4.1 weekly release. Note: New data reported by the Fed about the lending programs on June 19th indicate that using the level of net assets overstates the impact of these programs. Much of the data in Figure 2 represent Treasury capital contributions and not actual lending.