Most people know that Google dominates the online search market, but did you know that the company has become the biggest player in the digital ad market? That’s a problem not only for consumers, but potentially for society as a whole, argues former digital advertising executive Dina Srinivasan.

Last year, Srinivasan gained attention for her paper “The Antitrust Case Against Facebook,” which explained how the tech giant’s market dominance can harm the public, even though the product is ostensibly free. Now she focuses on Google and the enormous advertising empire that has grown into the company’s biggest money-maker. In her new paper, “Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets,” Srinivasan analyses the digital ad market and argues that Google’s monopolization and the giant regulatory gaps on matters like transparency and conflicts of interest have created an anti-competitive environment that can be harmful to newspapers, consumers, and, ultimately, democracy itself. She proposes that fairness can be restored by using principles applied to financial market regulation.

Lynn Parramore: After years of inaction, we’re seeing lots of headlines on antitrust actions against Big Tech. The Federal Trade Commission and the attorneys general of 48 states and territories have filed antitrust cases against Facebook, charging that it is able to abuse users’ data and violate their privacy. There are also several parallel suits against Google’s search dominance and chokehold on the advertising market. A good deal of the impetus to these suits comes from work that a number of researchers, including you, have done. How has our knowledge about both antitrust generally and Google and Facebook in particular changed over the last few years?

Dina Srinivasan: I think we have caught up with the fact that there is no such thing as a free lunch. Free does not necessarily mean good for the consumer. Free also doesn’t mean that there aren’t any antitrust problems in the market. For a long time, we thought we could simply ignore the social network and search markets because they were free to the consumer. Now we have historic antitrust cases brought in both markets. 48 attorneys general have initiated antitrust action against Facebook’s zero-cost social network to defend a people’s privacy. That’s fantastic.

In online advertising markets, we’re catching up with the fact that these markets operate and look like other electronically traded markets. This new perspective helps one understand when and why certain trading conduct is good or bad.

LP: Let’s talk about how the online advertising market works for the ordinary person. Say I’m waiting for the train and pull out my phone. I read a newspaper article about a recipe and then click on a cookbook ad. What’s been happening with ads while I’ve been doing my thing?

DS: In the milliseconds that it takes for that newspaper article to load, there’s a complex trade that concludes in the background. As soon as you visit that newspaper website, the newspaper’s sell-side middleman—called an ad server in online advertising markets—routes the empty ad space on that page to multiple ad exchanges.

Each exchange races to sell that ad space to the highest bidder in its little auction, hosting an auction and determining the highest bidder. An important point here is that the bidders here are not advertisers like Procter & Gamble or your local dry cleaner but these advertisers’ buy-side middlemen. You see, advertisers can’t bid directly on these new exchanges, just as you can’t bid or transact directly through the New York Stock Exchange.

After all the exchanges conclude their auctions, they send the highest bid back to the newspaper’s ad server. This sell-side middleman should then declare the highest bidder the winner of the newspaper’s ad space. That winner’s ad is then fetched and displayed to you on the page just in time for the page to finish loading. You probably didn’t notice anything happened at all: you just see advertisers’ ads alongside that recipe you are reading about.

LP: What is Google’s role in this advertising market? How did it influence what happened when I was online?

DS: Google operates the largest sell-side middleman, the ad server, the largest exchange, and the largest buy-side middlemen that bid on exchanges on behalf of advertisers large and small. This means that Google’s sell-side determines whether and how to route the newspaper’s ad space to the different exchanges. Google’s exchange then determines whether and how to let various buy-side middlemen representing advertisers bid on the ad space. Because Google has an overwhelming share of the buy-side market, this means that Google can often be the biggest bidder in Google’s own exchange.

LP: How important to the company are Google’s advertising activities compared to its search model?

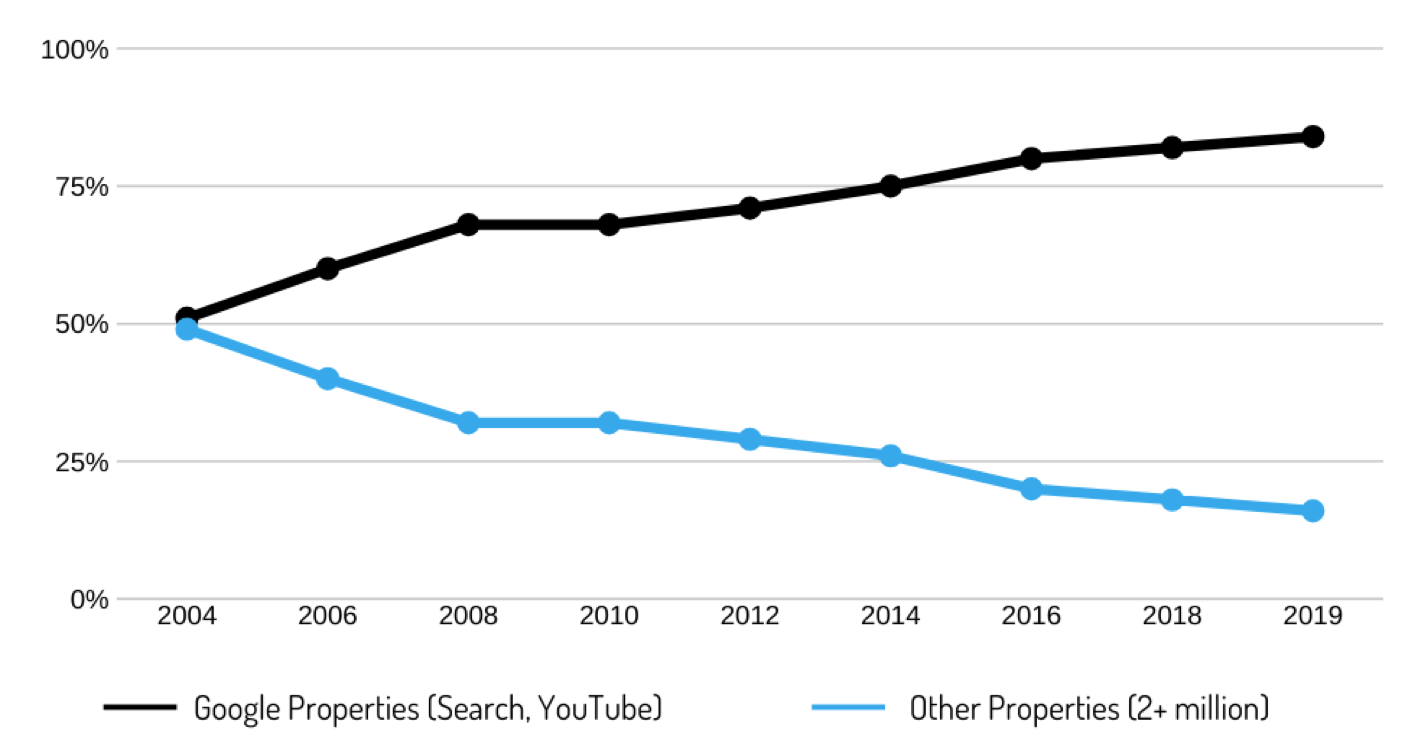

DS: Pretty important, as a graph[1] from my recent paper in the Stanford Technology Law Review illustrates. The critical thing to note here is that by owning the sell- and buy-side of the wider advertising market, Google can steer or allocate trades to its own properties, like Google search or YouTube. Trade allocation problems are also common in financial markets.

“Share of Google Ad Revenues Going to Google vs. Non-Google Properties 2004-2019”

LP: It’s not difficult to see how Google’s dominance of online searches might harm me: When I search for something online, Google can show me what it wants me to see, like a service it owns. But how do I get harmed by what Google is doing vis-à-vis online advertising?

DS: The invention of electronic trading is supposed to make the process of trading more efficient: less running around, less paper, fewer phone conversations. In the online advertising market, when an advertiser spends a million dollars purchasing ad space trading on exchanges, collectively, the trading intermediaries take 30-50 percent of that. So, the newspaper has to forgo a 300,000-500,000 dollar commission on those one million dollars-worth of ad trades. That’s a lot for an electronic trading market.

Consumers ultimately suffer, too. When newspapers have less money to invest in content or payroll, people have to pay more for subscriptions or newspapers go out of business and consumers have less news. Neither end is good for the business of news or democracy. And, when advertisers pay more for that ad space that they are buying, those costs are ultimately passed onto consumers in the form of higher prices for goods and services.

LP: You point out that Google gets away with all kinds of stuff that companies in other electronic trading markets are prohibited from doing. In financial markets, for example, we have rules against front running, insider trading, and order flow routing. Why is Google able to do things they can’t?

DS: Because we have not yet imposed trading rules in online advertising markets. There are no rules. We don’t regulate conflicts of interest. So, everything that does not fly on Wall Street, can possibly fly in ad markets. For example, for a long time, Google’s sell-side intermediary, DoubleClick, preferentially routed publishers’ ad space to Google’s exchange, even though Google’s exchange charges more than other exchanges. Google’s exchange also preferences Google’s buy-side bidding in Google’s exchange, with speed and information advantages. That also distorts competition.

LP: You’ve suggested that we could tackle failures in the online ad market by taking a few pages from the financial market regulation playbook. How would that work?

DS: We need to manage conflicts of interest: The company that runs an exchange can’t also operate on the buy- or sell-sides of the market. Alternatively, require those companies to have firewalls between business divisions, prohibit data leaking from one division to another, and prohibit the preferential routing of order flow. That is, manage those conflicts. But managing conflicts, as opposed to simply prohibiting them, would be a bigger lift for governments. For that reason, I think the first approach is superior.

LP: What are the biggest challenges to this type of regulation?

DS: I’d say politics.

There are also some changes related to browsers and privacy in the industry that present new challenges. Google’s Chrome browser will start to handle some of this ad trading process. So, after we implement those conflicts of interest rules between the buy- and sell-sides, and the exchanges, we now have a browser problem. How should we think about this? I think the answer here should follow the same path: We need to manage conflicts of interest, either through structural separations or conflicts of interest regulation (firewalls, etc.), and require disclosures and trading transparency.

Footnote

[1] Reprinted by permission of the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University, from the Stanford Technology Law Review at 23 Stan. Tech. L. Rev._(forthcoming 2020). For information visit: https://journals.law.stanford.edu/stanford-technology-law-review. Also, see: Srinivasan, Dina. “Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets,” Stanford Technology Law Review

Vol.24:1 (2020): 122.