The Idea That Businesses Exist Solely to Enrich Shareholders Is Harmful Nonsense

In a new INET paper featured in the Financial Times, economist William Lazonick lays out a theory about how corporations can work for everyone – not just a few executives and Wall Streeters. He challenges a set of controversial ideas that became gospel in business schools and the mainstream media starting in the 1980s. He sat down with INET’s Lynn Parramore to discuss.

Lynn Parramore: Since the 1980s, business schools have touted “agency theory,” a controversial set of ideas meant to explain how corporations best operate. Proponents say that you run a business with the goal of channeling money to shareholders instead of, say, creating great products or making any efforts at socially responsible actions such as taking account of climate change. Many now take this view as gospel, even though no less a business titan than Jack Welch, former CEO of GE, called the notion that a company should be run to maximize shareholder value “the dumbest idea in the world.” Why did Welch say that?

William Lazonick: Welch made that statement in a 2009 interview, just ahead of the news that GE had lost its S&P Triple-A rating in the midst of the financial crisis. He explained that, “shareholder value is a result, not a strategy” and that a company’s “main constituencies are your employees, your customers and your products.” During his tenure as GE CEO from 1981 to 2001, Welch had an obsession with increasing the company’s stock price and hitting quarterly earnings-per-share targets, but he also understood that revenues come when your company generates innovative products. He knew that the employees’ skills and efforts enable the company to develop those products and sell them.

If a publicly-listed corporation succeeds in creating innovative goods or services, then shareholders stand to gain from dividend payments if they hold shares or if they sell at a higher price. But where does the company’s value actually come from? It comes from employees who use their collective and cumulative learning to satisfy customers with great products. It follows that these employees are the ones who should be rewarded when the business is a success. We’ve become blinded to this simple, obvious logic.

LP: What have these academic theorists missed about how companies really operate and perform? How have their views impacted our economy and society?

WL: As I show in my new INET paper “Innovative Enterprise Solves the Agency Problem,” agency theorists don’t have a theory of innovative enterprise. That’s strange, since they are talking about how companies succeed.

They believe that to be efficient, business corporations should be run to “maximize shareholder value.” But as I have argued in another recent INET paper, public shareholders at a company like GE are not investors in the company’s productive capabilities.

LP: Wait, as a stockholder I’m not an investor in the company’s capabilities?

WL: When you buy shares of a stock, you are not creating value for the company — you’re just a saver who buys shares outstanding on the stock market for the sake of a yield on your financial portfolio. Public shareholders are value extractors, not value creators.

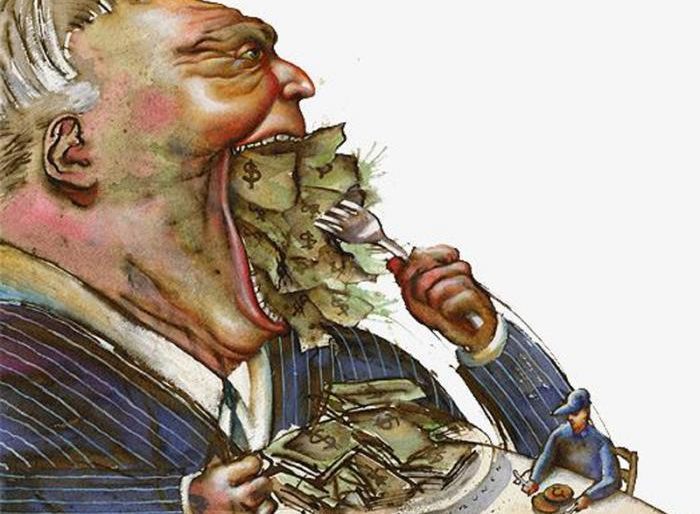

By touting public shareholders as a corporation’s value creators, agency theorists lay the groundwork for some very harmful activities. They legitimize “hedge fund activists,” for example. These are aggressive corporate predators who buy shares of a company on the stock market and then use the power bestowed upon them by the ill-conceived U.S. proxy voting system, endorsed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), to demand that the corporation inflate profits by cutting costs. That often means mass layoffs and depressed incomes for anybody who remains. In an industry like pharmaceuticals, the activists also press for extortionate product price increases. The higher profits tend to boost stock prices for the activists and other shareholders if they sell their shares on the market.

LP: So the hedge fund activists are extracting value from a corporation instead of creating it, and yet they are the ones who get enriched.

WL: Right. Agency theory aids and abets this value extraction by advocating, in the name of “maximizing shareholder value,” massive distributions to shareholders in the form of dividends for holding shares as well as stock buybacks that you hear about, which give manipulative boosts to stock prices. Activists get rich when they sell the shares. The people who created the value — the employees — often get poorer.

LP: You’ve called stock buybacks — what happens when a company buys back its own shares from the marketplace, often to manipulate the stock price upwards— the “legalized looting of the U.S. business corporation.” What’s the problem with this practice?

WL: If you buy shares in Apple, for example, you can get a dividend for holding shares and, possibly, a capital gain when you sell the shares. Since 2012, when Apple made its first dividend payment since 1996, the company has shelled out $57.4 billion as dividends, equivalent to over 22 percent of net income. That’s fine. But the company has also spent $157.9 billion on stock buybacks, equal to 62 percent of net income.

The vast majority of people who hold Apple’s publicly-listed shares have simply bought outstanding shares on the stock market. They have contributed nothing to Apple’s value-creating capabilities. That includes veteran corporate raider Carl Icahn, who raked in $2 billion by holding $3.6 billion in Apple shares for about 32 months, while using his influence to encourage Apple to do $80.3 billion in buybacks in 2014-2015, the largest repurchases ever. Over this period, Apple, the most cash-rich company in history, increased its debt by $47.6 billion to do buybacks so that it would not have to repatriate its offshore profits, sheltered from U.S. corporate taxes.

LP: But don’t shareholders deserve some of the profits as part owners of the corporation?

WL: Let’s say you buy stock in General Motors. You are just buying a share that is outstanding on the market. You are contributing nothing to the company. And you will only buy the shares because the stock market is highly liquid, enabling you to easily sell some or all of the shares at any moment that you so choose.

In contrast, people who work for General Motors supply skill and effort to generate the company’s innovative products. They are making productive contributions with expectations that, if the innovative strategy is successful, they will share in the gains — a bigger paycheck, employment security, a promotion. In providing their labor services, these employees are the real value creators whose economic futures are at risk.

LP: This is really different from what a lot of us have been taught to believe. An employee gets a paycheck for showing up at work — there’s your reward. When we take a job, we probably don’t expect management to see us as risk-takers entitled to share in the profits unless we’re pretty high up.

WL: If you work for a company, even if its innovative strategy is a big success, you run a big risk because under the current regime of “maximizing shareholder value” a group of hedge fund activists can suck the value that you’ve created right out, driving your company down and making you worse off and the company financially fragile. And they are not the only predators you have to deal with. Incentivized with huge amounts of stock-based pay, senior corporate executives will, and often do, extract value from the company for their own personal gain — at your expense. As Professor Jang-Sup Shin and I argue in a forthcoming book, senior executives often become value-extracting insiders. And they open the corporate coffers to hedge fund activists, the value-extracting outsiders. Large institutional investors can use their proxy votes to support corporate raids, acting as value-extracting enablers.

You put in your ideas, knowledge, time, and effort to make the company a huge success, and still you may get laid off or find your paycheck shrinking. The losers are not only the mass of corporate employees — if you’re a taxpayer, your money provides the business corporation with physical infrastructure, like roads and bridges, and human knowledge, like scientific discoveries, that it needs to innovate and profit. Senior corporate executives are constantly complaining that they need lower corporate taxes in order to compete, when what they really want is more cash to distribute to shareholders and boost stock prices. In that system, they win but the rest of us lose.

LP: Some academics say that hedge fund activism is great because it makes a company run better and produce higher profits. Others say, “No, Wall Streeters shouldn’t have more say than executives who know better how to run the company.” You say that both of these camps have got it wrong. How so?

WL: A company has to be run by executive insiders, and in order to produce innovation these executives have got to do three things:

First you need a resource-allocation strategy that, in the face of uncertainty, seeks to generate high-quality, low-cost products. Second, you need to implement that strategy through training, retaining, motivating, and rewarding employees, upon whom the development and utilization of the organization’s productive capabilities depend. Third, you have to mobilize and leverage the company’s cash flow to support the innovative strategy. But under the sway of the “maximizing shareholder value” idea, many senior corporate executives have been unwilling, and often unable, to perform these value-creating functions. Agency theorists have got it so backwards that they actually celebrate the virtues of “the value extracting CEO.” How strange is that?

Massive stock buybacks is where the incentives of corporate executives who extract value align with the interests of hedge fund activists who also want to suck value from a corporation. When they promote this kind of alliance, agency theorists have in effect served as academic agents of activist aggression. Lacking a theory of the value-creating firm, or what I call a “theory of innovative enterprise,” agency theorists cannot imagine what an executive who creates value actually does. They don’t see that it’s crucial to align executives’ interests with the value-creating investment requirements of the organizations over which they exercise strategic control. This intellectual deficit is not unique to agency theorists; it is inherent in their training in neoclassical economics.

LP: So if shareholders and executives are too often just looting companies to enrich themselves – “value extraction,” as you put it – and not caring about long-term success, who is in a better position to decide how to run them, where to allocate resources and so on?

WL: We need to redesign corporate-governance institutions to promote the interests of American households as workers and taxpayers. Because of technological, market, or competitive uncertainties, workers take the risk that the application of their skills and the expenditure of their efforts will be in vain. In financing investments in infrastructure and knowledge, taxpayers make productive capabilities available to business enterprises, but with no guaranteed return on those investments.

These stakeholders need to have representation on corporate boards of directors. Predators, including self-serving corporate executives and greed-driven shareholder activists, should certainly not have representation on corporate boards.

LP: Sounds like we’ve lost sight of what a business needs to do to be successful in the long run, and it’s costing everybody except a handful of senior executives, hedge fund managers, and Wall Street bankers. How would your “innovation theory” help companies run better and make for a healthier economy and society?

WL: Major corporations are key to the operation and performance of the economy. So we need a revolution in corporate governance to get us back on track to stable and equitable economic growth. Besides changing board representation, I would change the incentives for top executives so that they are rewarded for allocating corporate resources to value creation. Senior executives should gain along with the rest of the organization when the corporation is successful in generating competitive products while sharing the gains with workers and taxpayers.

Innovation theory calls for changing the mindsets and skill sets of senior executives. That means transforming business education, including the replacement of agency theory with innovation theory. That also means changing the career paths through which corporate personnel can rise to positions of strategic control, so that leaders who create value get rewarded and those who extract it are disfavored. At the institutional level, it would be great to see the SEC, as the regulator of financial markets, take a giant step in supporting value creation by banning stock buybacks whose purpose it is to manipulate stock prices.

To get from here to there, we have to replace nonsense with common sense in our understanding of how business enterprises operate and perform.