There is not one opioid crisis in America—there are many. And supply-focused measures won’t stop them.

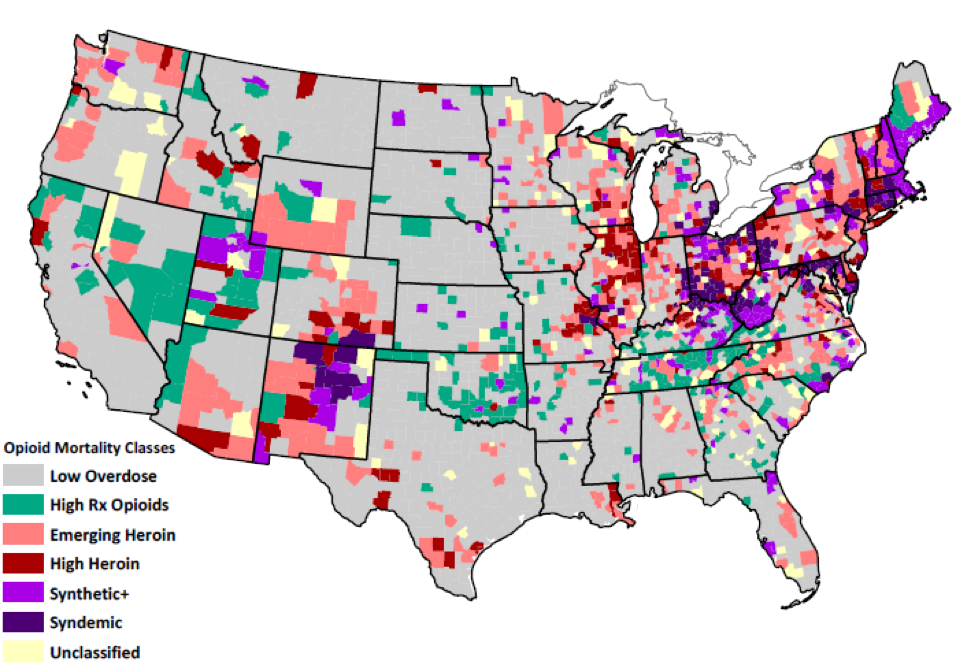

Over 400,000 people in the U.S. have died from opioid overdoses since 2000. However, there is widespread geographic variation in fatal opioid overdose rates, and the contributions of prescription opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl) to the crisis vary substantially across different parts of the U.S. In a study published today in the American Journal of Public Health, we classified U.S. counties into six different opioid classes, based on their overall rates and rates of growth in fatal overdoses from specific types of opioids between 2002-04 and 2014-16 (see Figure 1). We then examined how various economic, labor market, and demographic characteristics vary across these different opioid classes. We show that various economic factors, including concentrations of specific occupations and industries, are important to explaining the geography of the U.S. opioid overdose crisis.

Figure 1. Fatal Opioid Overdose Classes by County Note: Classes are based on absolute fatal overdose rates in 2014–2016 and the change in rates between 2002–2004 and 2014–2016. Analyses included 3,079 U.S. counties.

There are Multiple Geographically Distinct Overdose Crises in the U.S.

There is not one universal opioid overdose crisis in the U.S. There is significant geographic variation in deaths from prescription opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids. Most counties (58%) had low or average fatal opioid overdose rates and rates of change from 2002-04 to 2014-16. These low overdose counties are distributed throughout the southern and central U.S. and California. Nearly 9% of counties had high overall rates and high rates of growth in prescription opioid overdoses. High prescription opioid overdose counties are concentrated in southern Appalachia, eastern Oklahoma, parts of the desert southwest, Mountain West, and Great Plains.

High heroin counties (5.4%) and emerging heroin counties (14.5%) are geographically distinct from the prescription opioid counties and are concentrated in parts of New York, the Industrial Midwest, central North Carolina, and portions of the southwest and northwest. There are two classes where large shares of deaths involved multiple opioids, including fentanyl. The synthetic+ class (6.9%) has high and fast-growing fatal overdose rates from synthetic opioids alone and synthetic opioids in combination with prescription opioids and to a lesser extent, heroin.

Counties in the other multi-opioid class (4.2%) are in the depths of the opioid crisis, having very high and rapidly-growing fatal overdose rates from all types of opioids: heroin, prescription, synthetic, and combinations of the three. We term this class the “syndemic opioid class” because it reflects multiple concurrent or sequential epidemics, in which the combination of high overdose rates from multiple opioids greatly exacerbates the crisis. The synthetic+ and syndemic classes are concentrated throughout New England, central Appalachia, and central New Mexico.

On average, low overdose counties are less white and more rural than any of the high overdose counties. However, rural counties are most heavily represented in the high prescription opioid class; 73% of counties in the high prescription opioid class are rural compared to 35% in the syndemic class.

How are Economic and Labor Market Factors Related to the Geography of the Multiple Opioid Crises?

Fatal overdose rates are higher in counties characterized by greater economic disadvantage, more blue-collar and service employment, and higher opioid prescribing rates. High rates of prescription opioid overdoses and overdoses involving both prescription and synthetic opioids cluster in more economically-disadvantaged counties with larger concentrations of service industry workers. High heroin and syndemic opioid overdose counties (counties with high rates across all major opioid types and combinations of opioids) are more urban, have larger concentrations of professional workers, and are less economically disadvantaged.

High blue collar and service worker presence – what we might think of collectively as the “working class” – were associated with increased odds of being in all five of the high overdose classes versus the low overdose class. The nature of blue collar and service work might increase risk for work-related injury or physical wear and tear, thereby increasing demand for pain treatments within these contexts. Moreover, as shown in numerous in-depth accounts (Quinones, 2015; Alexander, 2017; Goldstein, 2017; Macy, 2018) declines in good-paying and secure employment for the working-class over the past four decades have manifested in collective psychosocial despair, population loss, family and community breakdown, and increased substance misuse.

Consider the cases of McDowell County, WV and Scioto County, OH, which are classified in our study as a high prescription opioid overdose counties. For several decades, McDowell County, West Virginia was the world’s largest coal producer, but McDowell has experienced massive and sustained population decline from 100,000 in 1950 when coal jobs dominated the area, to about 19,000 today (Pilkington, 2017). As coal declined, lower paying precarious service jobs became the main source of employment, but even those have disappeared. Even Walmart couldn’t make it there; it closed in 2016. McDowell now has among the highest prescription opioid overdose rates in the U.S.

A similar story unfolded in Scioto County, Ohio. In Dreamland, Sam Quinones (2015) wrote extensively about the city of Portsmouth, located in Scioto County. Portsmouth is blue-collar community with a once thriving manufacturing base anchored by shoe, steel, brickyard, atomic energy, and soda factories. By the 1990s, these factories were long gone, replaced by big-box stores, check-cashing and rent-to-own services, pawn shops and scrap yards, and the nation’s first large “pain clinic” where doctors doled out prescriptions for OxyContin and other narcotics like candy. Portsmouth was soon the pill-mill capital of America, with more prescription pain relievers per capita than any other place in the country. Today in Scioto County, incomes are lower than in the 1980s, and poverty, disability, and unemployment rates are all high. According to the latest Census data, 39% of prime working age males (ages 25-54) in Scioto County are unemployed or out of the labor force altogether.

McDowell and Scioto counties were among the canaries in the coal mine for the first wave of the opioid crisis that began with prescription opioids. Pharmaceutical companies capitalized on and exploited the underlying vulnerability to opioids in these places—drugs that numb both physical and mental pain. Interventions aimed at addressing the overdose crisis in places with large concentrations of blue collar and precarious service employment must consider the likely absence of alternative pain treatment services, underfunded public services resulting from community economic disinvestment and population loss, and the need for programs that address not just drug addiction but underlying chronic pain, trauma, and despair.

Ultimately our study suggests that national drug policy strategies, especially those that focus on specific substances, will not be universally effective across the U.S. For example, supply-side interventions targeting opioid prescribing are unlikely to be effective in places characterized by high rates of heroin and synthetic opioid overdose. It is also clear that economic factors matter for understanding the geography of the opioid crisis, and these are getting far too little attention from policymakers. Without attention to place-based structural economic and social drivers of the opioid crisis, supply-side policy interventions are unlikely to have any real sustained impact on reducing rates of drug addiction and drug-related deaths.

Alexander, Brian. 2017. Glass House: The 1% Economy and the Shattering of the All-American Town. St. Martin’s Press.

Goldstein, Amy. 2017. Janesville: An American Story. Simon & Schuster.

Macy, Beth. 2018. Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America. Little, Brown, and Company.

Pilkington, Ed. 2017 (July 9). What Happened when Walmart Left. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jul/09/what-happened-when-walmart-left.

Quinones, Sam. Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic: Bloomsbury Press; 2015