According to the 5th Afrobarometer survey (2011–2013), only slightly more than 50 percent of respondents in Sub-Saharan Africa view their national identity as more important than their ethno- linguistic group. The choice of national vs. ethnic identity is especially important in Sub-Saharan Africa because it directly affects economic development, public goods provision, corruption, and violence (Easterly and Levine (1997), Alesina et al. (1999, 2003), Gederman and Girardin (2007), and Baldwin and Huber (2010)).

One of the plausible explanations of low levels of national identity is civil conflict. Countries of Sub-Saharan Africa experienced more than 80 intra-state wars between years 1960 and 2008 (Sarkees and Wayman (2010)). Empirically, the effect of civil conflict on identity formation remains unclear with some studies documenting a negative effect on generalized trust and increase in ethnic salience (Rohner, Thoenig and Zilibotti (2013)), and some studies documenting the positive effect of civil conflict on social cohesion (Gilligan, Pasquale and Samii (2014) and Bauer et al. (2016)). Importantly, the existing literature only looks at the effect of civil wars on the attitudes of groups that are directly involved in conflict. This is a nontrivial limitation since, while the civil conflict does happen in Africa more often than in other parts of the world, most of the region’s population lives far away from the conflict zones.

To expand on the existing evidence, Ananyev and Poyker (2019) exploit a plausibly exogenous timing of insurgency in Northern Mali to estimate the effect of civil conflict on the groups not directly affected by conflict. We hypothesize that members of those groups would view the state as weak and incapable, since the state is not able to resolve tensions and avoid or stop the insurgency. In addition, information about civil conflicts can break up the successful coordination of identities if people choose their identities not only based on their own views but also on their perception of other peoples’ opinions. Using a representative geo-coded survey of Malian residents, we find — in a difference-in-difference framework — that the proximity to the conflict area negatively affects national identity and increases the salience of ethnic identity. The effect is not driven by the pre-conflict differential trends, access to public goods, or security environments. The effect seems to be larger for those residents who consume more local media.

The Tuareg-led insurgency in Mali in 2012 provides a unique context to identify the causal effects of civil conflict on national identity. Generally it is difficult to do so because regions with lower national identity may be more prone to revolts against the nation state. Alternatively, some regions may be economically and politically different due to ethnic favoritism (e.g., Posner (2005)), which is correlated with national self-identification and propensity for violence. In the paper’s setting, the Tuaregs have been striving to win autonomy for their homeland since Mali’s independence in 1960; however, the timing of the rebellion was plausibly exogenous to the Malian domestic political developments because it was a direct result of NATO’s involvement in the Libyan civil war.

This exogenous shock of insurgency allows us to address issues arising from possible reverse causality coming from the ethnic conflict as a symptom of weak national identity. Secondly, we address the latter concern (i.e., omitted variable bias), by concentrating analysis on the non-conflict areas and do not consider Tuaregs or Tuareg homelands.

The paper’s institutional setting is the Tuareg-led insurgency in Mali caused by the demise of the Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi. The Tuaregs first were hired by Muammar al-Gaddafi when the Libyan civil war started; they then returned to their homelands with their weapons after the Libyan regime had been defeated by NATO-led coalition. Three of the country’s nine regions — Tomboctou, Kidal, and Gao (collectively known as Azawad), all located in the northern Mali — are considered Tuareg homelands and have been the subject of a struggle for independence. For reasons stated above in our analysis we consider only non-Azawad regions (the border region of Mopti and other regions to the south of Azawad).

Thus, our identification is based on a variable-treatment-intensity difference-in-difference estimation, in which we compare respondents living closer to the border with Azawad to those living further away before and after the conflict; i.e., their treatment — proximity to Azawad’s border — is continuous. While respondents did not experience the damaging effects of the conflict in per- son, these residents were exposed to information about state weakness due to the rebellion.

This exposure came from two factors. First, the violence in Azawad triggered a refugee crisis that saw up to 400,000 Malians leaving their homes. Those refugees who wanted to move to more peaceful southern regions had to go southward from Azawad through Malian territory. Second, Malian army forces conducting antiterrorist fighting moved through Mali to get to Azawad. Army operations near the Azawad’s border led to civilian casualties and triggered intercommunal violence. Residents located closer to the border were therefore more informed regarding the state’s weakness.

We find a negative causal effect of state weakness on national identity using individual-level survey data from Mali. We use the third, the fourth, and the fifth Afrobarometer surveys, which were completed before (2005 and 2008) and right after the insurgency (2012), to construct the measure of national identity and measure the distance between border with Azawad and the respondent.

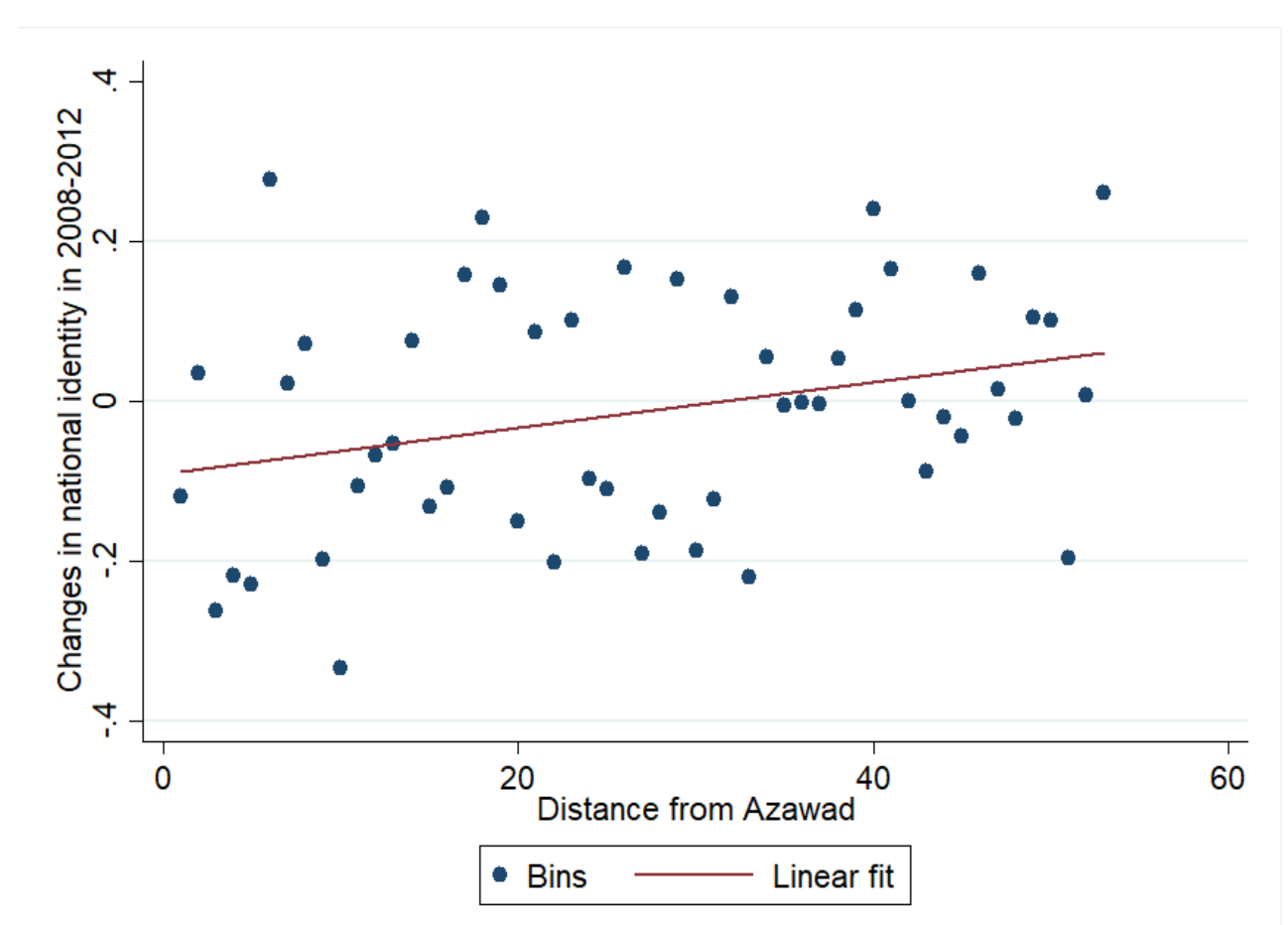

Figure 1 visualizes the main finding by demonstrating the reduced form relationship between the distance to the conflict zone (i.e., Azawad) and changes in national identity among Malian respondents between 2008 and 2012. Respondents living in villages and towns located closer to the border with Azawad experience a higher decline in national identity after the insurgency.

Figure 1: Distance to Azawad and changes in national identity between 2008 and 2012 Notes: Observation is a bin; i.e., all villages/towns are grouped in 55 bins for the sake of better representation. The blue dot represents the residualized differences between national identity before and after the Tuareg Rebellion.

In regression analysis, we find that national self-identification of the respondents located 100 kilometers closer to the border with Azawad experienced a 19.7 percentage-points larger decrease than those located further away. Given that before the latest instance of the Tuareg rebellion the share of people who had chosen the national identity was 69 percent, this is a substantial effect. The evidence also suggests that respondents who were located closer to the conflict zone and had higher exposure to media or were members of local community groups (conditional on other socio-demographic factors) experienced an even larger decline. One potential explanation for this heterogeneous effect is that receiving more information about the rebellion led people to reconsider their identities faster.

We also show that lower national identity salience was not explained by (i) worsening of local economic conditions, public goods provision, or increased violence; (ii) atrocities perpetrated by the Malian government; (iii) ethnic or ideological proximity of survey respondents towards the Tuaregs; (iv) changes in social cohesion and trust; (v) a particular subsample.

To investigate the channels of influence of conflict on national identity, we perform the same difference-in-difference estimations on several potential channels: trust in a national leader, trust in parliament, and trust in local leaders. We find that only changes in trust in national leader can be predicted by the distance from conflict zone, while other variables are not affected. We also find that the trust in national leader is a strong predictor of national identity.

To conclude, some see the construction of national identities as a great accomplishment of African postcolonial development: though African states have arbitrary borders drawn by European colonial powers, in the post-colonial period these imagined borders became a reality, and the African political map has proved remarkably resilient with comparatively few conflicts between states. While this is a considerable achievement, one might still wonder why construction of national identity is difficult in some circumstances and not in others, and why this number is not close to 100 percent. Our suggestion is that frequent civil conflicts in African countries may erode national identity, thus highlighting a reason why civil conflict is costly for growth and development.

References

Alesina, Alberto, Arnaud Devleeschauwer, William Easterly, Sergio Kurlat, and Romain Wacziarg. 2003. “Fractionalization.” Journal of Economic growth, 8(2): 155–194.

Alesina, Alberto, Reza Baqir, and William Easterly. 1999. “Public goods and ethnic divisions.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(4): 1243–1284.

Bahgat, Karim, Kendra Dupuy, Gudrun Østby, Siri Aas Rustad, Håvard Strand, and Tore Wig. 2018. “Children and Armed Conflict: What Existing Data Can Tell Us.” Technical report, PRIO.

Baldwin, Kate, and John D Huber. 2010. “Economic versus cultural differences: Forms of ethnic diversity and public goods provision.” American Political Science Review, 104(4): 644–662.

Bauer, Michal, Christopher Blattman, Julie Chytilová, Joseph Henrich, Edward Miguel, and Tamar Mitts. 2016. “Can war foster cooperation?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3): 249–74.

Cederman, Lars-Erik, and Luc Girardin. 2007. “Beyond fractionalization: Mapping ethnicity onto nationalist insurgencies.”

American Political science review, 101(1): 173–185.

Dippel, Christian, Robert Gold, Stephan Heblich, and Rodrigo Pinto. 2017. “Instrumental variables and causal mechanisms: Unpacking the effect of trade on workers and voters.” National Bureau of Economic Research.

Easterly, William, and Ross Levine. 1997. “Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions.” The quarterly journal of economics, 112(4): 1203–1250.

Gilligan, Michael J, Benjamin J Pasquale, and Cyrus Samii. 2014. “Civil war and social cohesion: Lab-in-the-field evidence from Nepal.” American Journal of Political Science, 58(3): 604–619.

Posner, Daniel N. 2005. Institutions and ethnic politics in Africa. Cambridge University Press.

Rohner, Dominic, Mathias Thoenig, and Fabrizio Zilibotti. 2013. “Seeds of distrust: Conflict in Uganda.” Journal of Economic Growth, 18(3): 217–252.

Sarkees, Meredith Reid, and Frank Whelon Wayman. 2010. Resort to war: a data guide to inter-state, extra-state, intra-state, and non-state wars, 1816-2007. Cq Pr.

Shaw, Scott. 2013. “Fallout in the Sahel: the geographic spread of conflict from Libya to Mali.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 19(2): 199–210.