Repeat after me: How much pipe should Fed plumbers lay if Fed plumbers like to lay pipe?

Short-term money markets seldom make headline news. But since mid-September, one of the most important components of the money market—the so-called “repo” market in which traders borrow from each other using securities as collateral — has been in almost constant turmoil. At one point, the market threatened to dry up, with borrowers paying rates as high as 10% per annum.

The question that this paper seeks to answer is why don’t US banks temporarily liquidate some or all of their excess reserves at the Federal Reserve when the repo rate surges so far above the rate they receive for holding on to them. Asset pricing theory tell us that the answer must lie in a blend of three ideas: (1) the way that the risk-free interest rate on excess reserves (the IOER) is being set, (2) the extent to which counterparties —the marginal repo-ers—might be experiencing a deterioration in their stand-alone default risk and in the quality of the collateral they offer, and (3) the price the market sets for bearing these risks.

At each maturity, elementary economic theory interprets the interest rate on collateralized loans as the sum of a riskless rate and a premium paid for accepting both a delay in collectability and the particular risks posed by borrowers and the collateral they offer.

This paper focuses on the Fed’s interest rate on excess reserves and how this rate and the Fed’s upper and lower targets for the fed funds rate distort the term structure of riskless rates. The key point is that the maturity of excess reserves is whatever a bank wants it to be. Paying the same rate for excess reserve balances irrespective of the counterparty bank’s planned maturity conflicts with the idea that the term structure for riskless rates should depend in part on expectations of future economic developments. Forecasting these developments cannot be done with any accuracy in this very uncertain world. Setting a single IOER, irrespective of maturity, distorts the yield curve for risk-bearing in that it is likely to subsidize risk avoidance at most horizons. In a word, the value of the option to let excess-reserve balances ride needs to be priced explicitly.

Plumbing Financial Liquidity

Liquidity is a three-dimensional term. A dealer market is said to be liquid when one can either establish or “liquidate” a substantial position quickly, at little cost, and without having much impact on the price of the asset exchanged. In targeting financial stability, Federal Reserve officials concern themselves directly with two kinds of liquidity: the liquidity of bank portfolios and the liquidity of markets for overnight funds.

Since they characterize their stabilization efforts as providing “liquidity,” it is natural to think of Fed officials as operating a combined fresh-water and waste-water treatment facility. Its reservoirs, pumps, and pipes contribute to the circulation of explicit liquidity and hard-to-observe implicit subsidies. Both products are piped through selected banks and securities dealers. Oversight of how fairly and efficiently the Fed’s directly connected banks and dealer firms retail these products to downstream businesses and households represents a poorly understood third product line.

In recent weeks, clogs have developed in two closely related markets for overnight funds. In one of these markets, the Fed makes collateralized loans directly to eligible firms. Because title to the collateral temporarily changes hands, these loans are called repurchase agreements or “repos.” The other market trades titles to reserve balances held at the Fed. Because the balances traded never leave the books of the Fed, tradeable claims to the balances are known as “federal (or fed) funds.”

Because the Fed usually prices its delicately plumbed products favorably, it is a privilege for a private financial firm to be allowed to connect some or all of its retail pipes and pumps directly to the Fed. Eisenbeis (2018) indicates that the Fed’s most important counterparties are money-market funds (who participate only in the repurchase-agreement part of the network) and 23 securities firms it designates as “primary dealers.”

Primary dealers are connected not only to the repo network, but they participate as well in the Fed’s daily open-market operations and in securities auctions that the Fed administers on behalf of the Treasury. More than half of designated dealers are subsidiaries of foreign institutions. The opportunity to trade directly with the Fed conveys to these firms a limited amount of pricing power and a corresponding duty to help the Fed to avoid and service “clogs” in their downstream distribution systems.

My metaphor for the network the Fed has built for distributing permanent and overnight liquidity raises at least three issues about the post-crisis banking scene. First, why are contingent safety-net guarantees and interest on excess reserves still being subsidized and shouldn’t well-off bankers –especially those domiciled in Europe— feel morally queasy about extracting subsidies from lower-income US taxpayers? Second, why aren’t the Fed’s charges for overnight liquidity characterized as deliberately underpriced fees paid for a temporary splash of liquidity rather than being framed less transparently as if they were interest payments on a collateralized loan? Third, should Fed officials feel an obligation to re-pipe its subsidy network to minimize the daily volatility of the explicit and implicit elements of the federal funds rate?

Managing the Liquidity in Fed Reservoirs: Paying Explicit Interest on Excess Reserves

Whenever the Fed releases some liquidity from its reservoirs, it flows through commercial-bank reserve accounts as excess reserves. Figure 1 shows that in the 25 years leading up to the GFC, banks did not allow excess reserves to stay on their balance sheets for very long. This is because the explicit return on these assets was zero and, in most circumstances, their implicit return was low as well. This miniscule return led policymakers to expect that bankers would put reserve inflows to work in new loans and investments more or less as soon as they could.

Economists have used this expectation of prompt bank recirculation to build a simplified dynamic model of the money-creation process. In this model, pumping a given amount of reserves into (or out of) the hands of profit-maximizing bankers shifts the supply of loanable funds to the right (left). The more elastic the demand for these funds, the larger the equilibrium change in the money supply. Everyone agrees that the usefulness of this theory broke down during the Great Depression.

But it is not easy to divide responsibility for this breakdown between customers’ reluctance to borrow and bankers’ reluctance to lend. It is also hard to get professionals in any field to abandon an established theory. As the Great Depression became an ever more distant memory, economists found it easier and easier to convince themselves that the problem during the 1930s lay not just in a drastic fall-off in loanable-funds demand, but in the timid way that Fed officials supplied new reserves. Outside the Fed, the money-multiplier theory was rescued from the scrap heap by adding the assumption that, when the economy is in crisis, central bankers have to have the courage to drive the level of excess reserves to great heights. To be effective, these new levels need to be high enough to spur insolvent and nearly insolvent banks into making loans at historically low rates of return in an extremely uncertain environment.

It seems clear that managers of zombie institutions find it useful to show an inordinate amount of excess reserves on their balance sheets. Whenever a bank’s earnings opportunities and asset values crash, excess reserves gain value in two ways. They reduce the near-term probability of having to face either a bank examination or a destructive customer run.

During the crisis, helping distressed banks to build up liquidity became a major goal of the Fed. The Fed made aggressive use of its discount window and emergency lending authority to pump liquidity directly into banks whose balance sheets were running dry. The explosion of creatively named Fed programs for lending to troubled institutions supports the hypothesis that establishing a reserve-abundant environment became temporarily an intermediate crisis-management target.

New loans made in this environment might actually lower a bank’s reported rate of return on its particular blend of fairly priced new assets and deliberately overvalued old assets. To buy time for various endgame gambles for resurrection to play out, zombie bankers have to put up numbers that falsely convey the impression that they could withstand either a run or a rigorous federal bank examination.

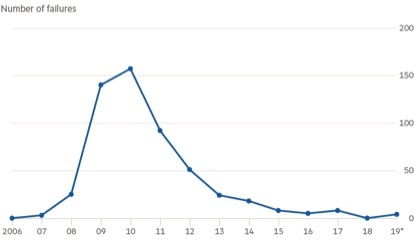

Inside the Fed, the expansion of excess reserves has been framed in terms of targets for interest rates, securities prices, and the flow of new mortgage loans. Nevertheless, Figure 1 shows that, during the Great Financial Crisis, the modern Fed seemed to confirm the lender-reluctance hypothesis by pumping out to its dismay almost three trillions of dollars in excess reserves. During this experiment, contrary actions taken in enhancing explicit returns on excess reserves and reallocating supervisory resources blurred the results of the exercise. Stepping up the number of bank examinations conducted each week and finding and closing insolvent banks at the rate of 3 per week (Figure 2) made excess reserves more valuable than ever. As in the nineteen-thirties, weak and insolvent banks (whose priorities were avoiding and surviving bank examinations and customer runs) took their sweet time in putting excess reserves into play.

Explicit Interest on Excess Reserves

Shortly after Lehman failed in 2008, the Fed sought and received Congressional permission to accelerate the date of its previously-authorized ability to pay explicit interest on bank reserves. Wall (2015) characterizes the Fed’s request as part of a plan meant to set a floor on interest rates that would prepare federal-funds traders for a return to an environment of scarce reserves and to the system for trading these reserves that went with it.

When income, employment, and credit demand finally began to pick up steam, the Fed’s liquidity-distribution metaphor reframed the crisis-driven buildup of excess reserves –going forward— as an overfilled reservoir of bank liquidity. This way of thinking led Fed officials to worry excessively about the inflationary consequences of a possible flood of liquidity as banks’ return to solvency destroyed their need to hold onto excess reserves as a screening device.

To slow the release of liquidity from reserve accounts during the post-crisis era, Fed policies encouraged banks –explicitly and implicitly—to release excess-reserve balances cautiously. In view of: (1) banks’ legacy of unbooked losses, (2) the high rate of ongoing bank closures, and (3) the slow recovery of customer demand for bank funding, it is doubtful that quite so much encouragement was needed. But fear of being blamed for initiating a new round of high inflation and a concern for the survival of almost-solvent banks in the system made it seem reasonable for Fed officials to step up the role of explicit interest on reserves.

From the Fed’s earliest days, the costs and benefits of requiring banks to hold reserves was a point of contention between the Fed and the banks. For many years, the Fed softened the burden of reserve requirements by offering its member banks a series of clearing, settlement, currency, and safe-keeping services that were not fully priced. It is useful to interpret this pricing scheme as a form of implicit interest on members’ reserve balances.

In the 1980s, lobbying pressure from large banks that competed with the Fed in the market for interbank services persuaded Congress to pass legislation that increasingly restricted the Fed’s ability to underprice its services (see Kane, 1982). To limit opportunities for banks to escape reserve requirements by surrendering their memberships in the Fed, Congress tried to balance the bargain by extending the reach of Federal Reserve requirements to nonmember banks. But other kinds of regulatory arbitrage continued to undercut the effectiveness of these requirements.

This is how Fed officials came to look for new ways to influence aggregate reserves and eventually to support the idea of paying explicit interest on reserves held at the Fed. In the midst of the banking crisis in late 2008, the Fed was permitted to pay explicit interest as an emergency measure. To make the rate on these balances into a more-powerful crisis-management tool, Fed leaders decided to accrue interest on required and excess reserve balances alike. Paying banks explicit interest on balances held in excess of the amount that is legally required is equivalent to creating for banks only a Treasury bill whose maturity is at the option of the holder. Variation in the level of the rate which banks receive on these excess reserves [the “excess reserve rate” or (in Fedspeak) the IOER] has gone on to become –along with the rates the Fed offers on repurchase agreements— a lead instrument in the Fed’s tool cabinet.

Early in the crisis, the fed funds rate sank to a near-zero level, so that the higher return offered on excess reserves began to pump a larger and larger flow of subsidies to banks that chose not to dump their reserves into the market. The resulting decline in reserve circulation persuaded Fed officials to revitalize the instrument of open-market operations. They christened the one-way transactions that fighting the Great Financial Crisis entailed first as “large-scale asset purchases,” but journalists and traders renamed the program more colorfully as Quantitative Easing. Quantitative Easing (which became QE in Fedspeak) pushed policymakers into a scheme that resembles a reverse version of Paul Volcker’s 1979 targeting scheme. Fueling the pumps for large open-market purchases entailed: (1) allowing mortgage-backed securities issued by Fannie and Freddie to enter into the range of securities purchased in Fed open-market operations and (2) expanding what had begun as a roughly one-trillion dollar securities portfolio by over 3.5 trillion dollars.

The main method Fed officials used to restore bank solvency was to subsidize the return that could be earned on excess reserves, although Fed officials deny that this was their intention. The idea of paying interest on required reserves at the level of their opportunity costs has a distinguished intellectual pedigree and a legitimate policy purpose (Wall, 2017). But their search for new controls in the midst of a crisis led Fed leaders to blow past the opportunity-cost restriction. Because the IOER is meant to be available only to FDIC-insured banks, Fed officials felt free to allow the market-equilibrium fed funds rate to lie below the return on excess reserves (sometimes for days on end). This policy turned the rate paid on excess reserves into a subsidized[1] and inherently discriminatory instrument.

One of the principal themes of my research has been to show that discriminatory policy instruments generate creative forms of circumvention that eventually destroy the policy’s discriminatory effect. So it is with the IOER. To allow large nonbank institutions and accredited (i.e., wealthy) household investors[2] to earn the excess-reserve rate (minus a small fee), several ex-Fed employees chartered a controversial narrow and uninsured bank[3] (TNB USA Inc.) in Connecticut. A narrow bank is one that takes no risk. The social value of such a bank was originally framed as a hypothetical way to eliminate the need for a government safety net. But until an explicit return on excess reserves emerged, no risk meant no profit because narrow banks could never earn enough on safe assets to be viable. The Fed has so far refused to give TNB a reserve account (I suppose) on the grounds: (1) that TNB is not and cannot become an insured bank because its charter does not allow it to accept retail deposits[4] and (2) that TNB’s only purpose for existence is to circumvent a particular Fed rule. As in other cases of blatant regulatory arbitrage, the legality of this scheme will finally be settled in the courts.

It doesn’t take much imagination to see that, if nonbank parties are willing to pay a fee to TNB to get a piece of the return offered on excess reserves, the return on excess reserves is out of line with other short-term rates. The best justification for subsidizing returns on excess reserves is to prevent a rapid monetization of excess reserves. But the level of subsidization is itself generating arbitrage activity that transforms other types of short-term funding into higher-rate excess reserves. Authorities need to understand that creative regulatory arbitrage won’t stop with TNB. Innovative arrangements will keep coming until the subsidy the IOER conveys is effectively eliminated.

The root of the problem is that Fed officials are simultaneously trying to unwind QE and to align four closely related explicit rates and fees: its discount rate, the corridor of upper and lower target rates it sets for fed funds, and the return on excess returns. Administered target rates move once in a while, but market rates on similar assets and liabilities move continually. As market rates fluctuate, some Fed-administered target rates become too high and others become too low. Both in the US and abroad, it is the job of savvy financial engineers to plow through this wave of closely related opportunities to garner handsome minute-to-minute returns on short-term balances. Such creative arbitrageurs routinely search out minor differences in explicit and implicit interest rates on various instruments to generate profits on rewarding trades of their devising.

Chairman Powell has characterized such arbitrage as a “technical issue” (Miller and Matthews, 2019). But it is much more than that. It seems clear that the setting the IOER too high during and after the Great Financial Crisis has had important macroeconomic consequences. It made holding excess reserves attractive enough to render the private supply of federal funds less elastic. Elementary price theory tells us that, given an unchanged environment of seasonal, daily and intraday shifts in the demand for liquidity, this decrease in the elasticity of supply should increase the volatility of the fed funds rate.[5]

Bank portfolio theory has even more to say. Subsidizing bank holdings of excess reserves tempts American offices of foreign banks to raise funds in negative interest-rate European environments and put them to work as excess reserves at the Fed. This arbitrage is helping to keep a number of foreign zombie banks alive at our expense. At the same time, the availability of long-lasting subsidies must also be expected to alter the domestic financial industry’s equilibrium portfolio too, reducing interbank lending and loans to business and households in the process.

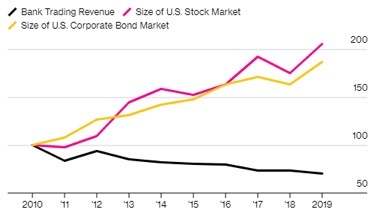

The increase in the volatility of the repo and fed funds rates have further incentivized a number of important banks to repurpose their reserve-management staffs as arbitrage traders in short-term contracts of all sorts. Figure 3 [taken from Armstrong (2019)] shows that, since mid-2018, JPMorgan (in particular) has been selling off loans and increasing its holdings of directly tradable securities. While Armstrong portrays this shift as an effort to arbitrage differences in capital requirements on loans and securities, I think the greater usefulness of securities as collateral in other forms of regulatory arbitrage is more important. In the face of a doubling in the size of major US financial markets, his graph shows that banks’ explicit revenue from trading has been falling. Given that a doubling has been observed in bank stock prices, it is likely that clever accountants see to it that returns from regulatory-arbitrage trading accrue in accounts with less-informative names.

A prolonged difference between the fed funds rate and the sum of (1) the excess reserve rate and (2) the option value of being able to move funds almost costlessly between excess reserves and other opportunities is by no means a technical issue. This gap disrupts the risk structure of bank returns by establishing —for banks only— an unusually high rate of return on a risk-free opportunity.

I have no doubt that the availability of this outsized daily return has retarded bank-financed economic growth during the post-crisis era. Fed officials deliberately set too high a floor on the yield banks could earn by holding ultrasafe and optional-maturity excess reserves. This made it possible for more than a few US banks to wait out the post-recovery period of painfully low interest rates and feeble (and uncertain) loan demand. Besides distorting the domestic price of risk bearing, the gap between the IOER and negative interest rates in Europe and Japan set up carry trades that were —and still are— being exploited by foreign institutions and domestic money-market mutual funds. Since the Fed could stop this exploitation (if they wanted to) by eliminating the explicit return on excess reserves, one has to conclude that Fed officials believe that supporting zombie banks in foreign lands benefits US interests.

How Does the Sum of Explicit and Implicit Interest Collected on an Overnight Basis Differ from a Simple Fee?

For the use of one-day funds, the short answer to the question posed in the section heading is that there is no substantive difference between a simple fee and a one-time payment, no matter how the amount due might be calculated. A fee is a payment made for a professional or public service. Fees are typically paid in the coin of the realm. Framing a one-day fee as a per annum interest rate attaches unnecessary emotional significance to the volatility observed when it changes. For example, a 10 percentage-point move —which might quadruple the repo rate on a given day— translates in dollar terms into a fee increase of only $0.10/360=$1/3,600. Though the increases in either measure are proportionately the same, the emotional contexts differ. An increase of 0.27 pennies in a per-dollar fee does not trigger age-old concerns that make the increase seem usurious.

A second advantage of looking at the price of overnight funds as a fee is that it leads us to think of the trouble of finding, evaluating, securing, and returning collateral as an unavoidable additional and implicit fee. Characterizing movements in the cost of a repo transaction solely in terms of an explicit repo rate fails to acknowledge the ways that explicit and implicit fees substitute for each other. A temporary shortage of easy-to-transfer collateral should persuade private lenders both to accept and to price explicitly an equilibrium increase in collateral risk. A reduction in the average quality of the collateral a counterparty can offer may be expected to call for an increase in the explicit fee charged for the funds. Allowing borrowers to post a less-secure type of collateral increases the explicit rate on repos, but reduces the unobserved implicit fee that borrowers would have incurred if they had been forced to post higher-quality collateral.

QE has left the Fed holding trillions of dollars of Treasury securities that it is reluctant either to cancel[6] or to sell off quickly. These assets could allow the Fed to reduce spikes in the equilibrium collateral-quality costs that banks experience simply by developing programs for lending out (i.e., “repo-ing”) high-quality items from its securities portfolio. Since mid-September 2019, Fed officials have taken pride in doing the opposite of that. Because the Fed acts as the counterparty to the repo writer, its position deserves to be called a “reverse repo.”

In response to surges in the explicit overnight repo rate Fed officials have written reverse repos that have absorbed as much as $100 billion in high-quality collateral on a single day (Derby, 2019). They have also proposed to lay down a new layer of reverse-repo piping in the form of a permanent facility for engaging in term (i.e., longer than one-day) reverse repos (Dizard, 2019).

Although the public has been encouraged to think of these new pipes as serving as a vital “liquidity lifeline,” the Fed ought to look for ways to provide liquidity in ways that do not layer microeconomic problems on top of macroeconomic ones. Bankers and Fed officials have offered no evidence that risk-based volatility in the fee charged for overnight funding threatens the life of healthy banks or enhances the welfare of society in a specified way. Without evidence that the risks of these transactions are being mispriced, it is premature for policymakers and their client megabanks to think that taxpayers need to hand the Fed yet another instrument with which to subsidize the financial sector.

Why are megabankers and Fed officials so concerned with movements in the explicit part of overnight repo fees anyway? Although spokespersons have portrayed spikes in the fed funds rate as evidence of a market failure, it is more likely a consequence of surges in the default and information risks generated by the changing transparency and financial strength of repo and federal-funds traders, especially foreign ones.

Taxpayers deserve to know who would actually benefit from further subsidizing private traders and who would be made to bear the costs. Subsidizing the banking system in this additional way opens up new avenues of regulatory arbitrage and makes no economic sense unless one can identify a corresponding benefit to customers and ordinary taxpayers. I doubt that a less-elitist government would see a need to invent yet another way to run subsidies through the Fed’s plumbing system.

This episode seems little more than an updated case of the Fed’s age-old susceptibility to regulatory capture and money-market myopia. In popularizing the latter term, Karl Brunner used to add that the Fed is always looking to add one more “key” to its already-vast instrumental policy keyboard. But it is important to ask how this new “facility” might differ from the Fed’s age-old discount rate and discount window? The main differences would seem to involve a change in the policy narratives that a new facility can accommodate. Fed policymakers, rather than individual banks, would initiate these deals. This means that that little so-called “stigma” would attach to banks that use the new facility to borrow from the Fed. The Fed would also seem to control the maximum amount and collateralized character of the funds that could move through the new facility at any time.

But the discount window and discount rate would still exist. I have always thought of the “stigma” attached to using the discount window as merely another of the Fed’s many policy instruments. We should not forget that the stigma originated as an implicit “surcharge” invented to discourage interest-rate arbitrage in the 1950s and 1960s (see Goldfeld and Kane, 1966). Today, the stigma is nearing the end of its useful life. Expanding the Fed’s reverse-repo keyboard seems less efficient than building connections into technology-driven new forms of “banking” and reframing the stigma as a counterproductive vestige of a slower-moving financial past.

[1] Wall (2011) explains that Fannie and Freddie (and Federal Home Loan Banks as well) were routinely selling federal funds (because they could not themselves legally earn interest on their reserve balances at the Fed) at rates below the reserves rate to banks who could re-post the same funds as interest-bearing reserves. This activity helped to drive the funds rate below the Fed’s announced target, but the Fed chose not to take countervailing action.

[2] Retail deposits are defined as deposits made by individuals who are not “accredited investors” under federal securities regulations.

[3] A narrow bank takes deposits and invests only in super-safe assets.

[4] I would add that avoiding the assessment fees that the FDIC levies on the assets of insured banks plays a critical part in TNB’s business model and in reducing the profitability of domestic US banks’ efforts to arbitrage differences between the funds rate and the reserves rate (Wall, 2015).

[5] Of course, the Fed’s Open Market Desk could easily control this volatility directly by engaging in repos throughout the trading day.

[6] Since these securities are intragovernmental debt, cancellation would affect Fed earnings and net worth, but have no direct effect on bank reserves. If accountants can help banks to offset actual losses by creating intangible phantom capital accounts such as deferred tax assets and core deposit intangibles, they can invent similar accounts for the Fed. The simplest approach would be to plug in an intangible value for its franchise.

Figure 1 Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Figure 2: Surge in the Number of Bank Failures in the US During the Financial Cri *Through November 15. Source: FDIC. Copyright FT.

Figure 3: Revenue Booked as Trading Fees Has Slumped Even as Major Markets Have Grown Rapidly Sources: Financial Times based on Bloomberg data, Coalition. Note: Normalized with 100 representing size in 2010. 2019 figures are based on current pace for explicit trading revenue and Sept. 30, 2019 figures for market size.

References

Armstrong, Robert, 2019. “JPMorgan Pours $130 bn of Excess Cash into Bonds in Major Shift: Capital Rules Push US Banks to Sell Off Loans from its Balance Sheet,” Financial Times (Nov. 3).

Derby, Michael S., 2019. “New York Fed Official Says Market Interventions Have Restored Calm: Lorie Logan Who Is Acting Leader of the Markets Desk at the New York Fed, Said Efforts Are Working Well,” Wall Street Journal (Nov. 4).

Dizard, John, 2019. “Federal Reserve Standing Repo Facility Is Coming into View.” The Financial Times (September 26).

Eisenbeis, Robert A., 2018. “The Narrow Bank: Issues for the Fed and What Problems Does It Solve.” Slideshow Presentation for AEI Seminar (December 3).

_____, 2019. “Repos.” Slideshow Presentation for Cumberland Advisors (October).

Goldfeld, Stephen M., and Edward J. Kane, 1966. “The Determinants of Member-Bank Borrowing: An Econometric Study,” Journal of Finance, 21 (September), 499-514.

Kane, Edward J., 1982. “Changes in the Provision of Correspondent Services and the Role of Federal Reserve Banks Under the DIDMC Act,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 16 (spring), 93-126.

Miller, Rich, and Steve Matthews, 2019. “Jerome Powell Says Fed to Resume Portfolio Growth But It’s Not QE,” News Wire (Oct. 8).

Wall, Larry D., 2011. “Three Individually Reasonable Decisions, One Unintended Consequence, and a Solution,” Notes from the Vault, Center for Financial Innovation and Stability, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (May/June).

_____, 2015. “The Impact of Regulation on Monetary Policy,” Notes from the Vault, Center for Financial Innovation and Stability, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (January).

_____, 2017. “Interest on Reserves,” Notes from the Vault, Center for Financial Innovation and Stability, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (February).