Thou canst not say I did it. Never shake thy gory locks at me.

This week (March 14, a Friday in 2008) marks the tenth anniversary of the first Federal Reserve System emergency loan to (or for the benefit of) Bear Stearns and Company. The parentheses are needed because that first loan technically went to JPMorgan Chase, which acted as a conduit channeling Federal Reserve credit to Bear Stearns.

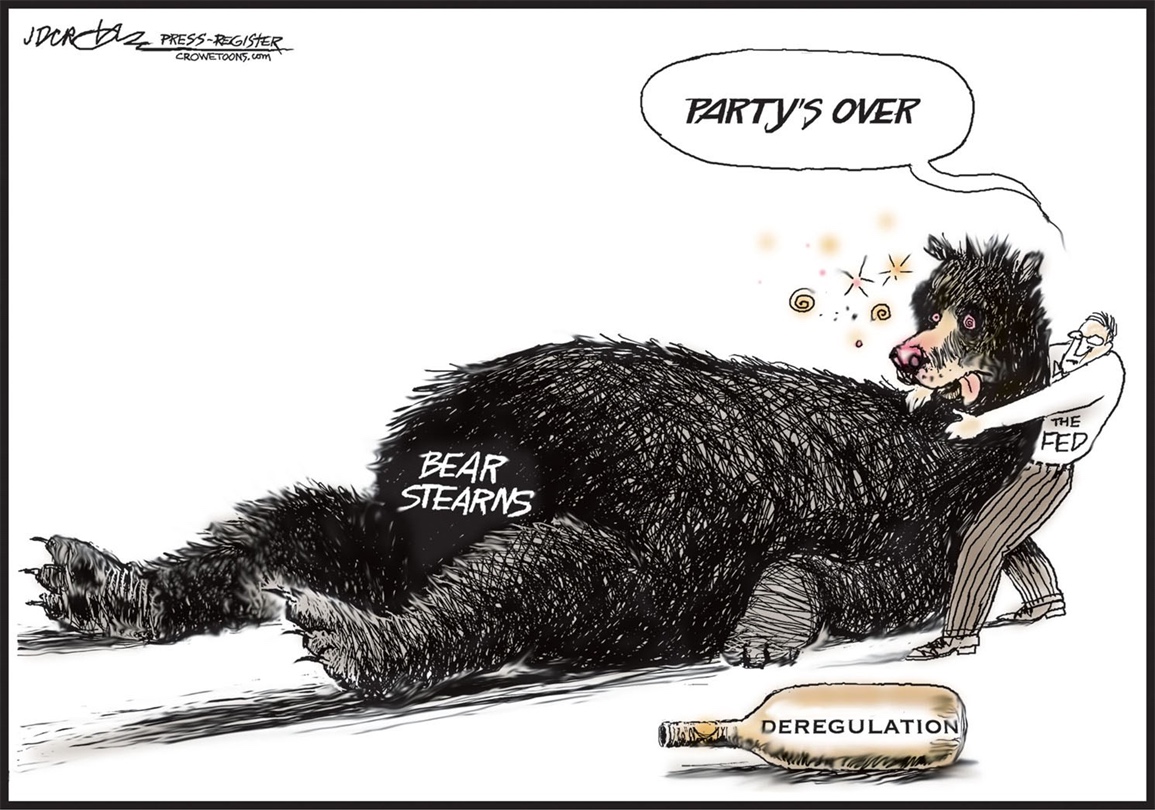

Estimates at the time indicated that Bear Stearns had leveraged its capital up to 35 times going into its final crisis. That is, the firm had no more than a 3 percent risk-absorption cushion during a period of increased market volatility. By Thursday night, March 13, 2008, Bear Stearns no longer could cover its liabilities as they became due at par value, which traditionally were established tests for the viability of any securities firm.

How one judges what happened next depends largely on one’s view of (a) how the financial world works plus (b) how loss absorption is supposed to work. Financial market practitioners usually divide into two camps: First, those who believe, somewhat cynically, that there is no difference between (a) and (b)—blame-shifting and loss avoidance are typical; and second, those who believe that, however financial markets work, finance always should be held to traditional standards of good faith, fair dealing, and market-value solvency.

The Bear Stearns episode was a watershed moment in the unwinding of the 2008 financial crisis, whose main blows were reserved for September of that year. Too much financial, regulatory, and moral rot had been allowed to build up in the framework of financial markets after 1992, in an almost unbroken chain of smaller excesses leading to greater excesses, for one to say that, if the Bear Stearns failure been handled differently, then the fall 2008 crisis could have been avoided or at least rendered milder. But it was clear at the time and became luminously clear afterward that the efforts to rescue Bear Stearns and its creditors paved the road to mishandling both that fall crisis and the subsequent recovery efforts.

Emergency Lending Before and After Bear Stearns

Emergency lending to large financial institutions, whose continued existence may depend on maintaining public confidence, usually carries with it the elements of secrecy and deniability illustrated by the quotation from Macbeth above. Preserving plausible deniability is one of the supreme goods pursued in Washington whenever breaches of good faith, fair dealing, and market-value solvency are discovered.

So it is with emergency lending in America. The bedrock statute, now Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, even before its amendment in the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, authorized the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors, by a positive vote of at least five of the seven Governors, to declare “unusual and exigent circumstances” allowing the Federal Reserve Banks to make emergency loans to “individuals, partnerships, and corporations.” From its inception in 1932 Section 13(3) restricted the collateral acceptable for such loans to the types that ordinarily were eligible for use at the Reserve Banks’ discount windows. That eligible collateral usually was understood to be either United States government securities or financial paper arising from current transactions in commerce. Securities firms like Bear Stearns ordinarily did not hold enough eligible collateral to be of much use in a financial crisis.

To make discount window credit available to securities firms, representatives of the Securities Industry Association, their main lobbying group at the time, arranged for the insertion of a clause in the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvements Act of 1991 (FDICIA) that replaced the eligibility-for-discount clause regarding collateral in Section 13(3) with a new one allowing the collateral to be anything satisfactory to the Reserve Banks. That change occurred in the final markup hearing and had not been presented in any hearing or floor debate on the bill.

At the time (1991 and after), staff members who pointed out this statutory change in Reserve Bank publications were criticized within the System for doing so. The procedural sanctions that the Board’s staff imposed on critics were for flagging the statutory change: such undermining of plausible deniability was intolerable in a Washington context. Still, 2008 approached with no actual use of Section 13(3) since 1936, even though discussion of it within the Federal Reserve System occurred frequently in intervening decades.[1]

Emergency lending takes place in the shadows, especially when the Federal Reserve undertakes it. The classic and structurally much sounder approach is to have Congress appropriate funds in a politically accountable manner for a Federal lending authority. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) or the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) of the 1930s come to mind as exemplars of this approach. Putting emergency lending authority into the Fed, with all its secrecy and avoidance of political accountability, is akin to giving that authority to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). One might well puzzle whether anyone in his or her right mind and not allied with major banks would advocate such a thing.

The Call to Action

As Bear Stearns slid toward failure over the weekend of March 14-16, 2008, several eyebrow-raising events occurred. First, on Friday, March 14, was the contemporaneous embrace of conduit lending from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) through JPMorgan Chase to Bear Stearns. Conduit lending has happened from time to time in the past and skates on thin moral ice, but it avoids full invocation of Section 13(3). The FRBNY agreed to lend up to $25 billion to JPMorgan Chase to be channeled onward to Bear Stearns, secured by acceptable collateral that Bear Stearns posted with the FRBNY. The president of the FRBNY at the time was Timothy Geithner, soon to become the Secretary of the Treasury, who remained at the FRBNY throughout the fall 2008 crisis.[2]

Negotiations continued through Friday to find a takeover partner for Bear Stearns. The leading candidate always was JP Morgan Chase, which was the principal clearing bank for Bear. Bear Stearns also was one of the principal clearing brokers for both credit-linked derivatives and mortgage-backed securities, including pools of subprime mortgages that then were experiencing a great deal of stress.[3] Bear Stearns also owned some valuable real estate, its headquarters building in midtown Manhattan, then estimated to be worth $1.2 billion. Over the weekend, JPMorgan Chase reached a deal with Bear Stearns to buy the entire firm for $2 a share (shares had been worth $170-plus only a little over a year earlier), but that deal collapsed when Bear Stearns shareholders objected to a sale at such low valuation (about $240 million for the entire firm, building and all). Bear Stearns shareholders approved the takeover about a week later when JPMorgan Chase raised its offer to $10 a share, a valuation of about $1.2 billion, which the building alone would cover.

Sunday, March 16, arrived with the Fed facing a dilemma. Bear Stearns offices in London and elsewhere in Europe were scheduled to open overnight Sunday New York time. Worse yet, the Board of Governors was short-handed, with only five sitting Governors. One, Frederic Mishkin, had been in Helsinki, Finland, and was not scheduled to arrive back in Washington until after the emergency loan funds had to be disbursed. Thus, five Governors would not be present to vote approval of a Section 13(3) emergency lending declaration to fund Bear Stearns so that it could open on Monday. Although the statute always required the positive vote of five Governors to approve any emergency lending declaration, the Board apparently adopted rules since 2003 allowing smaller numbers to act in an emergency.[4]

At this point, accounts differ. One version, consistent with reality, is that the remaining four Governors decided to approve a Section 13(3) loan anyway, to be ratified retroactively when Governor Mishkin arrived at the Board after the loan funds had been disbursed. He apparently did go to the Board and signed the relevant documents when he returned to Washington. When commercial bankers do this sort of thing for their customers (disbursing loans before all relevant documents are signed), they draw criticism from bank examiners, if not criminal charges.

The other version says that the Board never was worried about lack of authority anyway because of regulatory interpretations essentially saying that whenever the Board was required to have a supermajority vote, it could satisfy statutory requirements by unanimous vote of all members present and voting (“available”). Thus, four Governors would do.

Critics object that the Board was unauthorized to apply the supermajority override principle to Section 13(3). After all, the Board of Governors is chartered by Congress, and Congress (not the Executive Branch) has power over monetary affairs (Article I, Section 8, clause 5, U.S. Constitution). More persuasively on the presumptive absence of authority, Congress left the five Governors requirement in place in the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, two years after four Governors invoked Section 13(3). Also, even though the Board, strictly speaking, is not an Executive Branch agency, it often either complies with Executive Orders affecting the Treasury or other agencies or departments (usually when Congress directs by statute that it do so). The Board also engages in “parallel compliance” under its own set of rules that reflect the content of Executive Orders.[5]

Monday, March 17, 2008, the Bear Stearns loan approached $30 billion, dwarfing all prior Fed loans of any type. During the day, negotiations for purchase by JPMorgan Chase resumed, and the final deal, effective March 18, Tuesday, was as follows: the FRBNY would open a Primary Dealer Credit Facility (a form of Section 13(3) loan) for Bear Stearns. Instead of lending against collateral posted by Bear Stearns, the FRBNY would use that facility to purchase assets from Bear Stearns up to $30 billion. JPMorgan Chase agreed to take a $1 billion “first loss” on those possibly overvalued assets, but it also acquired a building valued at $1.2 billion. On June 26, 2008, the FRBNY created a subsidiary corporation, Maiden Lane LLC, to hold the assets purchased from Bear Stearns. Similar entities, Maiden Lane II and III, were created in September 2008 to hold assets purchased from AIG, the then-failing insurance company.

By Wednesday, March 19, 2008, the Bear Stearns loan grew to $28.8 billion outstanding. A week later, the Primary Dealer Credit Facility held $37.0 billion of assets, of which $5.5 billion may have come from borrowers other than Bear Stearns or JPMorgan Chase. The peak amount for the Facility came in the reserve accounting week ending April 2, 2008, $38.1 billion. Once Maiden Lane LLC was organized, its asset holdings were $28.8-$28.9 billion (see Table 2 in the Board’s weekly H.4.1 statistical releases, starting July 2, 2008). The big reduction in Maiden Lane holdings happened during calendar year 2011, falling from $27.0 billion to less than $7.2 billion by the year’s end. Maiden Lane LLC now holds assets valued at $1.7 billion. Table 4 in the current H.4.1 release (March 1, 2018) has the following note:

The remaining outstanding balances of the senior loan from the FRBNY to Maiden Lane LLC, and the subordinated loan from JPMorgan Chase & Co. to Maiden Lane LLC were repaid in full, with interest.

Maybe so, but the interest rate was below market, and the loans were outstanding a long time (three years before the large reduction began). After all, the word “emergency” implies, in this case, a form of credit bridge to a long-term investment by someone other than oneself. That bridge proved to be three years long, and the forthcoming tenth anniversary still finds $1.7 billion under the Fed’s asset management.

Was the Bear Stearns Bailout Loan Ever a Good Idea?

In my view, no. If it were a good idea, then the Maiden Lane assets would have found buyers at or near par value earlier than three years after acquisition. And the Fed would not still have nearly $2 billion of Maiden Lane assets on its books.

Are There Long-Term Negative Consequences of the Bailout?

Yes. Obviously $1.7 billion amounts to a rounding error in the Fed’s now bloated $4.4 trillion balance sheet. But that balance sheet was only about $900 billion in the week before the Bear Stearns bailout. More than concern about the principal amount of the Bear Stearns loan and the loans to others that followed in the fall of 2008, one should note that these emergency loans set in motion events that led eventually to Quantitative Easing and successor QE movements that inflated the balance sheet.

Hannah Arendt once wrote that the problem with new political economy models (she was thinking of modern fascism and Soviet-style communism, but the observation applies to all new ideas) is that afterward they remain on the shelf, an ever-present temptation for subsequent politicians to reach for them at the next crisis. Bailout lending, especially of the Section 13(3) variety, is crony capitalism writ large and is the type of temptation that Arendt was warning against. Bailout lending needs to stop. Eternal vigilance on the part of the public is the only remedy against it.

But alas, this Jim-dandy new fiscal toy – do not ever delude yourself into thinking that bailout lending is a proper monetary policy tool – now appeals to those who would have opposed it in earlier, more normal times. Just this week I read an account of how Section 13(3) lending could be used to pay off failing state and municipal pension plans, for example. One can imagine “needy” municipalities falling all over themselves in their haste to reach the discount window and to line up for the next round of loans.

Finally, moral and ethical standards, especially those for the fair treatment of taxpayers, are violated by bailout lending. Why bother exhibiting good faith and fair dealing in one’s financial transactions when, with the appropriate degree of political muscle, one can persuade the Fed’s hierarchy to lend first and ask questions later? At the FRBNY in recent years, President William Dudley and both of his successive general counsels have made public speeches before banking groups exhorting them to observe higher standards in their banking behaviors. But an insistence on good faith, fair dealing (treat your customers as the Fed treats you), and market-value accounting will go further in accomplishing the necessary overhaul of the international financial community and its supervisors than a policy of bailouts first, with hectoring after.

In the 1930s, banks that failed or sought bailout loans had to give up dollar-for-dollar warrants on their common stock (one warrant per dollar lent). When the banks returned to profitability, the warrants could be sold if the banks failed to repay their loans in a timely manner. The warrants served as a type of “equity kicker” for the public and, if invoked, would compensate the public at least partially for the risk that it bore. Senior officers of assisted banks also used to be required to submit formal letters of resignation to the supervisors, who then were free to act on the letters later if they deemed management incompetent. These useful traditions appear to have died sometime in the 1980s, in favor of far more banker-friendly policies. They should be revived. They promote good faith, fair dealing, and market-value accounting.

Acknowledgments: Much useful assistance and commentary was provided for this article by Thomas Ferguson and Edward J. Kane. Any remaining defects in this article are entirely of my own doing. The views expressed here are my own and should not be attributed to any institution with which I am now or have been affiliated.

Footnotes

[1] See, e.g., David Fettig, “Lender of More Than Last Resort,” The Region (December 1, 2002), Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

[2] See “Minutes of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System,” March 14, 2008. The relevant excerpt is as follows:

As required by the Federal Reserve Act [Note: statutory section not specified] when fewer than five Board members were available to approve an extension of credit to any individual, partnership, or corporation under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, all available Board members then in office unanimously determined, in connection with the authorization of the extension of credit, that (1) unusual and exigent circumstances existed; (2) Bear Stearns, and possibly other primary securities dealers, were unable to secure adequate credit accommodations elsewhere; (3) this action was necessary to prevent, correct, or mitigate serious harm to the economy or financial stability; (4) the other Board member in office could not participate in the Board’s action by any reasonable means at the time Board action was required (Governor Mishkin was unavailable because he was in transit from Helsinki, Finland, from 6:20 a.m. EDT to 5 p.m. EDT); (5) this action was required before the other Board member could return and/or participate by any available means; and (6) any credit extended will be payable on demand. (Emphasis supplied.)

[3] On the latter, see the book or movie, The Big Short (movie in 2015), or read Reckless Endangerment, by Gretchen Morgenson and Joshua Rosner (2011).

[4] See, e.g., Federal Reserve System, “Rules of Organization,” Federal Register, vol. 82, pp. 55496-55497 (November 22, 2017, effective October 25, 2017); also in 12 C.F.R. Part 265. The Board’s rule waiving the statutory requirement of five positive votes for Section 13(3) emergency declarations apparently was inspired by the events of September 11, 2001, and dates from 2003 (revision of Federal Reserve Regulation A on the discount window, 12 C.F.R. Part 201) but is based on no particular statute. The Board’s summary of the 2017 rule states as follows:

In addition, the Board has provided a modified definition of a quorum during exigent circumstances. In connection with this modification, the Board is amending its Rules Regarding Delegation of Authority, published elsewhere in this Federal Register, to authorize the Chair (or Vice Chair, if the Chair is unavailable) to determine when an emergency situation exists.

[5] These points about activation of Section 13(3) are discussed more thoroughly in Walker F. Todd, Chapter 12, “Macroliquidity: Selected Topics Related to Title XI of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2015,” in James R. Barth and George G. Kaufman, eds., The First Great Financial Crisis of the 21st Century: A Retrospective, vol. 9 (2016), pp. 299-336. Singapore: World Scientific—Now Publishers Series in Business (USA office: Hackensack, NJ). On the use of Section 13(3) for Bear Stearns, see Anna J. Schwartz and Walker F. Todd, “Why a Dual Mandate Is Bad for Monetary Policy,” International Finance, vol. 11, no. 2 (Summer 2008), pp. 167-183.