How does the influential text which is our focus (Mas-Colell, Whinston and Green’s Microeconomic Theory, or MWG) define its subject? It states that “microeconomic theory as a discipline begins by considering the behavior of individual agents and builds from this foundation to a theory of aggregate economic outcomes” (p. xiii). It also identifies a “distinctive feature” of microeconomic theory as being that “it aims to model economic activity as an interaction of individual economic agents pursuing their private interests” (p.3). However, to the best of our knowledge, no formal definition of microeconomics is provided in the book. Rather, a definition of microeconomic theory is suggested implicitly by these descriptions and by the body of argument which follows. This terse ‘non-definition’ is typical of the level of attention to contextual concerns in this influential text. The primary method of the text is to show rather than tell what microeconomists — at least these ones – do, although there can be found occasionaldeclarations concerning the nature of the subject and its sub-fields.

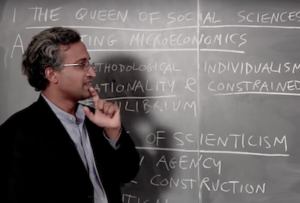

In this initial blog post we wish to situate microeconomics as a field of social enquiry. We accordingly, at the risk of some simplification, describe standard microeconomics (exemplified by MWG) as a branch of rational choice theory, which possesses three central tenets: methodological individualism, a certain view of rationality linked to constrained optimization, and a role for equilibrium as a descriptive and explanatory device. We then turn to broader questions concerning the ‘predicament’ of the ‘social sciences including economics.

Microeconomics and Rational Choice Theory

What is microeconomic theory? How can we better contextualize the subject and understand its role? To state the obvious, in MWG and related texts microeconomics is approached as a branch of rational choice theory - a highly influential approach in the “social sciences” which has extended its reach from economics to political science and a range of other disciplines. It might not be exaggerating to state that rational choice theory has become so successful that it is the “common sense” of much of the mainstream “social sciences” and of standard economics in particular (in which it is so much part of the air which is breathed that it is rarely even recognized as a theoretical stance). Rational choice theory (including its expression in microeconomic theory and in MWG) can be characterized in terms of the following three conceptual commitments:

1. Methodological Individualism

Economic and social processes and outcomes are to be characterized as the consequence of the actions of individual actors, understood as single minds associated with and in control of single bodies. [This latter characterization is less innocent then it seems. It does not lead to straightforward application even in such central domains for microeconomic theory as the theory of consumer choice, let alone the theory of the firm; concepts such as the role of the unconscious or the separation of ownership and control may wreak havoc in these respective domains]. The individual provides the ostensibly privileged starting point for analysis, from which all description, explanation and prediction follow.

Can all phenomena be best understood by invoking the interest of the individual in this way? We may find that in certain situations, aggregative concepts, especially those which invoke commonality of positioning in society in some relevant respect (such as gender, class, caste, race, ethnicity, age, estate, etc.) can be useful for generating certain kinds of explanations in spite of the fact that these explanations are not directly reduced (even if reducible) to a description of individuals (on which see e.g. the classic riposte to the doctrine of methodological individualism by Steven Lukes). There has recently also been considerable interest in shifting the level of analysis to other planes (e.g. the biological, considering the role of genes or other biological factors as individual units engaging in some level of evolutionary competition for resources and survival). It has been argued by some ‘reductionists’ that some phenomena (for example why individual organisms may appear to sacrifice themselves on behalf of other individuals to which they are related) cannot be explained without an appeal to dynamics operating on a plane other than that of the organism (in particular involving genetic mechanisms such as ‘kin selection’). Whatever view one may have on the (de)merits of specific such arguments, the methodological challenge posed by the fact that there may be multiple overlapping plausible planes of analysis, each of which claim priority for their own level of explanation, is evident: which is to be favored? Can such distinct layers of explanation be made compatible or must one choose one (the most reductive?)? What role should be played by judgments that particular descriptive categories are most salient for specific descriptive or explanatory purposes (even if not every purpose)? What is the role of connections between distinct layers of explanation? In economics and social affairs, for example, can we avoid thinking about the mutual determination and distinct histories involved in the presentation of explanations at distinct levels (e.g. institutions and individuals)?

2. Rationality and Constrained Optimization

Individual actors are taken to be (or at least to be fruitfully described as being) “rational” in the sense that they possess objectives and pursue (consistently, in the specific sense of that word defined by the theory) these objectives. Moreover, they are typically understood to do so relentlessly, maximizing and not merely satisficing.They take note of the constraints which they face and choose the course of action which furthers their objectives (or more to the point, objective, since multiple ends, possibly distinct in type, are collapsed to a unitary end such as utility) to the greatest extent given the existence of these constraints. The objective taken to be pursued by the agent is formally empty in that it can accommodate various substantive goals. However, it is typically (even if not always) understood to be characterized in terms of “private” interests (as we are informed by MWG). The individual’s choice is taken to be possible to interpret as if the situation (including constraints or choice alternatives) is understood by that individual and as if the individual accordingly pursuing her objectives (relentlessly). It is for this reason that MWG highlight (p.5) that ‘the theory need not be based on a process of introspection but can be given an entirely behavioral foundation.’.

The concept of rationality, of course, is used outside of economics in diverse disciplines (e.g. philosophy, sociology, political science, psychology, etc.) with varying characterizations. In microeconomics as exemplified by MWG, the description of rationality is reduced to the transitivity and completeness of preferences, and the “consistency” in choices that “reveal” such preferences (MWG, Ch. 1). There is so much to say about this set of concerns (which we will return to in due course) that I will not do so here, except to flag the distinction between a narrow conception of rationality involving a ’ foolish consistency’ and a broad conception involving the possession of ‘good reasons’ for doing what one does. [Raphaele Chappe will soon present a detailed blog post raising some critical questions about this understanding of rationality].

3. Equilibrium

The description, explanation and prediction of ‘social’ phenomena involving the interaction of agents is taken to be best achieved through the conceptual device of ‘equilibrium’.The concept of equilibrium typically combines the idea that agents are each pursuing their individual objectives to the maximal extent and the idea that these activities are mutually compatible.This compatibility can be in the aggregative sense that their social consequences (e.g. quantity demanded and quantity supplied of a good) can be combined without giving rise to a requirement for adjustment or in the more specific sense that individual agents’ plans or actions reinforce one another (the plans or actions of each agent can be ‘justified’ given the objective she is pursuing and the plans or actions of other agents).

Why is equilibrium prioritized as an explanatory concept and what role is there for understanding dis- and non- equilibrium dynamics?

The Predicament of Social Enquiry

Notably, little or no attention is given in the introductory pages of the text to broader questions concerning the ‘predicament of social enquiry’, which might include the following:

1. Human Agency And Its Implications

What is required of social enquiry if we take seriously the idea that human beings can change as well as choose (and choose how to change)? [We may call this a thick rather than thin view of human agency, where the latter is identified with choosing the maximal element in a choice set given fixed and extant preferences]. What level of predictability of human action is compatible with such an idea? If human beings’ objectives are revisable, and they learn about their preferences, desires and the world itself through ongoing experience in it, how well-defined, or stable, can human objectives be taken to be? Are ‘constraints’ in human affairs ever hard? If they are revisable then in what way should the possibility of revising them figure in our account (and in our understanding of the narrative that individuals maximize subject to constraints)?

2. The Social Construction of Economic Concepts

In what ways are economic concepts the contingent product of shared social understandings (and as a result the product of specific histories which could have taken a different turn)? If economies were organized differently, and economic actors and their objectives were described differently, what might that (or should that) imply for the concepts appearing in microeconomics textbooks? In what ways does the enterprise of microeconomic theory proceed from a narratival choice as to how best to describe the economic process and in what ways is it (or ought it to be) given by the ‘facts’? Even if it is claimed that the premises worthy of exploration in microeconomic theory are given by ‘facts’ (for instance the characterization of firms as organized to make profits for shareholders rather than for managers or of workers as motivated to generate income with which to finance consumption rather than by the intrinsic rewards of work) would it make a difference to our understanding of microeconomics as a ‘science’ whether these facts vary over economic systems and historical time? Is microeconomic theory supple enough to accomodate adequately such contextual variations and if not how would it need to be different to be able to do so?

3. The Political Role of Economic Theory

Ideas about how the economy functions may at times serve particular interests, whether directly or indirectly. This may in turn create enabling conditions or incentives for those interests to shape economics in certain ways or cause certain ideas to be ‘selected’, even if there is not express intention to do so. How does the ‘force field’ created by this social and political role affect economic ideas generally, and microeconomic ideas in particular? Even if one shies away fom a laden term such as ‘ideology’, in what ways does standard micreconomic theory reflect or reinforce the ambient common sense of ‘market culture’ (notwithstanding its high theoretic mathematical form).

4. The Role of Mathematics: Signifying Nothing?

A theory can have a mathematical form, and indeed involve an apparently ‘sophisticated’ formal structure, without being correct. It is possible to consider any arbitrary set of axioms, and proceed to explore their joint implications by elaborating chains of propositions, theorems and so on. Indeed, it may be possible for an army of persons to occupy themselves in such an activity, proceeding from common premises. However, the axioms, or the conclusions derived from them, may have a poor correspondence to facts in the world. The complexity of a theoretical edifice, and even less its mathematical content, fails to establish the scientificity of a research enterprise. As we know from physics and other disciplines which use mathematics (and in which it appears ’ unreasonably effective’) there are points at which one mathematical formulation is chosen over another, often on grounds of empirical evidence (see the early chapters of the recent book, The Trouble with Physics, for some apposite twentieth century examples). Such discrimination is at the core of scientific activity. Moreover, there are sciences (evolutionary biology being one example) in which the historical element is crucial to our understanding and the role of mathematics, although important, is confined to the description and explanation of particular structures or processes. Here too the choice of the specific premises in a mathematical model, and the quality of their representation of salient empirical facts, is crucial to the success of an activity of description, explanation or prediction.

It may be argued that it is not the job of the authors of a specialized technical text such as MWG to ask broad questions situating their enterprise. However, we think it is our job to do so, because of the functions which MWG and texts like it play in the discipline. We are interested not only in ‘authorial intention’ but in the ‘reception’ of the text by those who read, use and cite it, insofar as this bears upon the ways in which we think (or do not think, as the case may be) about the discipline of economics.