Since the Republican Party’s alternative to Obamacare passed the House of Representatives in May, the debate over health care in the United States has erupted anew. While his party tries to overcome warring factions to push its “repeal and replace” legislation, President Donald Trump himself called the House bill “mean,” while official estimates say 22 million people would lose health coverage under the Senate version. Protests over these proposals have broken out across the country, from Capitol Hill to members of Congress’ town halls in home districts.

Economists, too, are divided on what model of health care will ultimately be best for the American economy. But most agree that the status quo cannot continue indefinitely. A significant contingent, including Nobel laureate and INET grantee Joseph Stiglitz, view a single-payer system—in which the government (the “single payer”) covers the cost of health care for every citizen—as the only viable model in the long run.

An inefficient system

Much of the economic argument in favor of single payer centers on the question of efficiency. The need for hospitals to sift through mountains of insurer-related paperwork keeps administrative costs extremely high, and these costs are passed on to consumers. This inefficiency is compounded by a problem of asymmetric information built into the structure of the American health care system. The average consumer of health care has limited information on the quality of a given insurance plan, and shopping between plans—and accurately assessing the difference in quality between each—is difficult.

The result of these problems, say some economists, is a fundamental failure in the market for health care, which is distributed unevenly and uneconomically among consumers.

Anders Fremstad, Professor of Economics at the University of Colorado, observes that consumers consistently overpay for health care because of inefficiency, and that many are discouraged from seeking it at all due to the complexity of the system. Economist Dean Baker, Co-director and Founder for the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C., agrees, citing the inefficiency linked to the current multi-payer system as the most compelling factor driving the need for single payer.

Drawing a comparison with the United Kingdom, in which health care is paid for and distributed by the government, Baker notes that “part of the greater efficiency of the U.K. system is the fact that their hospitals and doctors don’t have to shuffle endless papers back and forth to collect from competing insurers, along with the various copays and deductibles that must be paid by the patient.”

Baker argues that this blizzard of paperwork imposes administrative costs not only upon the health care system as a whole, but also upon the patient. He or she must expend time and energy puzzling through how much they owe for each visit, as opposed to paying a straightforward proportion of their income annually to the government, as is the case in a single-payer system. Baker also cites the role of protectionism in the pharmaceutical and health care industries, which keeps costs in the U.S. artificially high compared to other countries. In his view, the government practice of granting monopolies to pharmaceutical companies has resulted in unreasonable price gouging of lifesaving medicine. Protectionist regulations governing who can practice health care practice keep doctors’ salaries high, he says, because there is little competition from foreign-trained competitors.

Like Baker, Julie Nelson, Professor of Economics at University of Massachusetts Boston, notes the logistical hurdles the private insurance-based system engenders.

Simply keeping track of whether a person is covered, what they are covered for, where they can receive care, and who gets billed for what consumes endless hours of time on the part of those in need of care, and bloats the offices of providers, insurers, employers, and program agencies.

Nelson posits that a move away from an employer- or private insurer-based system will have a net positive effect on efficiency because workers will no longer need to consider the availability of insurance when deciding whether to take or leave a job. As a result, they will be more likely to take up employment that they enjoy and that fits their skill set, without being restricted in terms of hours or location. As a self-described feminist economist, Nelson also notes a further single-payer benefit: Employers would not be able to limit access to contraception or any other procedures on the basis of religious freedom arguments.

What the numbers say

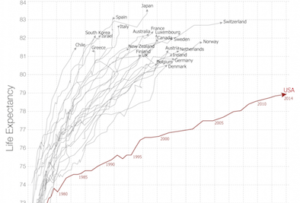

Other economists emphasize that empirical evidence appears to favor single-payer. Robert Pollin, Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Co-Director of the Political Economy Research Institute, notes that in the U.K., Germany, Japan, and other major developed nations, costs for health care make up only between 9 and 12 percent of GDP, while in the US spends closer to 17 percent of GDP. Yet, as he stresses, all of these countries perform better than the U.S. according to standard public-health measures such as average life expectancy.

Pollin was one of four authors of a recent report assessing the potential economic effects of California’s single-payer health care bill, which recently passed through the state’s Senate.

We found that the proposed Healthy California measure will generate [substantial] financial benefits for both families and businesses at all levels of the California economy.

To these financial arguments, he adds moral reasoning in his case for single-payer, which for him is “the organizing principle through which decent health care can be delivered to everyone in the U.S. as a basic human right.”

Why the government should be the payer

L. Randall Wray, Professor of Economics at Bard College in New York, criticizes the framing of single-payer health care as “universal health insurance.” Wray argues that a single-payer health care system would in reality need to operate very differently than a universal health insurance program—largely because the concept of covering health care through an insurance system in the same way that we cover our homes or cars is fundamentally flawed. He explains that going to the doctor is not like going to the auto repair shop: Humans require consistent, preventative health care, and for-profit insurance isn’t designed to provide it.

Wray notes that home or auto insurance is designed to be a “bad deal” for consumers, who pay premiums throughout their lives to protect themselves in the rare event that their house catches on fire or they get into a high-impact car crash. Health care is different because coverage isn’t just about catastrophe: Most costs go toward routine or preventative care, like annual checkups. As Wray puts it, routine health care is “not analogous to an ‘act of God’ that destroys your house: It is predictable, welcome, and life-enhancing.”

Economist Gerald Friedman, also of University of Massachusetts Amherst, has similar concerns about applying insurance companies’ profit-based business model to health care coverage. Such an arrangement leads to “adverse selection,” he says. Friedman explains that because of the concentration of health care spending on a few sick and injured individuals, private insurers will seek to save costs by identifying and avoiding such people— a practice called “lemon dropping”—while attracting the healthy—or “cherry picking.” Even with Obamacare protections around preexisting conditions, insurers are able to drop out of the Obamacare market altogether. While these strategies are profitable for insurers, they raise costs for consumers, putting those who can least afford to pay at risk.

Like Baker, Friedman is also concerned with the soaring price of pharmaceuticals and hospital services in the U.S., and argues that only a single-payer system can reverse the trend:

A system with multiple insurers leaves none with the market power to stand up to elite providers, including drug companies and hospitals.

Over time, Friedman argues, a single-payer system will not only cut costs, but also significantly improve the quality of health care and lead to more innovation and deeper research. For example, there are currently no data on outcomes and health care utilization across the country other than those collected by the VA and Medicare. The mass of data a single-payer system would accumulate—across the population and over time—would open doors to more conclusive research and “allow for quality analysis of treatment and provider behavior,” says Friedman. In the long run, he says, such data—and the system that produces it—could revolutionize the way health care is practiced in the US.