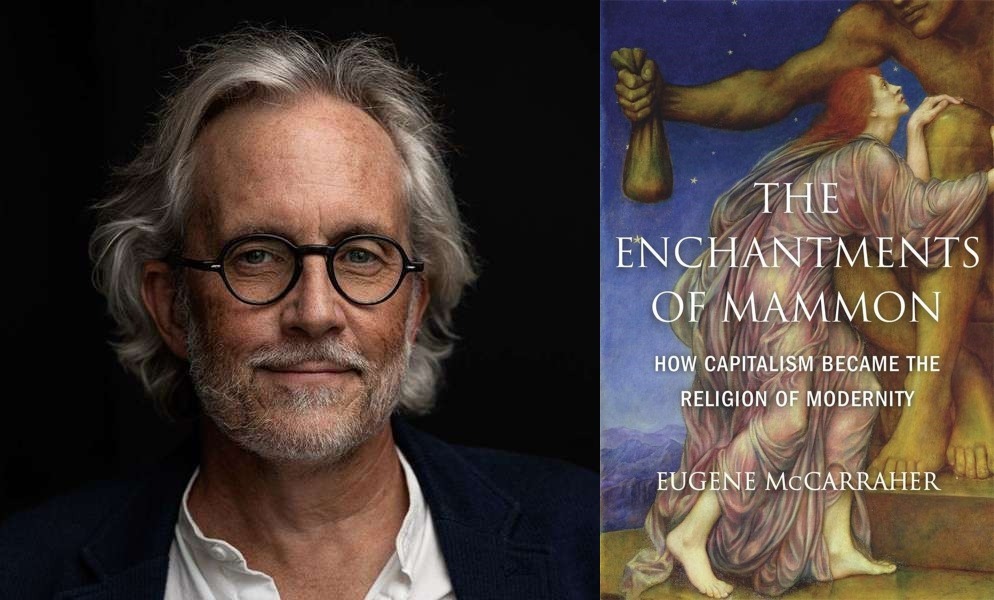

The latest book by Villanova University’s Eugene McCarraher, who teaches humanities, is a deep dive into the history of a perverted love story and a false religion — the western worship of money and markets. The author testifies against a creed that has dominated our lives since the 17th century and offers an imaginative look at what can help us break the spell. In the following essay, cultural historian Lynn Parramore discusses The Enchantments of Mammon: How Capitalism Became the Religion of Modernity. (For a recent conversation with McCarraher and Institute for New Economic Thinking president Rob Johnson, tune into this episode of the “Economics & Beyond” podcast).

Do you, inhabitant of the marvelous and menacing late-modern world, detect something missing – some kind of vitality, meaning, connectedness, love, beauty, or wonder? If so, you’ve likely searched for a story to explain it.

A popular narrative offers that something rather ugly happened on the way to modernity. As the Middle Ages gave way to the upheavals of the Reformation, the Enlightenment, and rising capitalism, a vanguard of scientists, professors of reason, Protestants, and money men (for they were almost always men), sought to break the shackles of the past. They fashioned bold new ideas and ways of being, but in doing so crimped the human spirit and frayed the ties that bind us to our neighbors, to nature, and to our own hearts. Even the needful and cherished material objects in our lives — the cooking pot, the plow, the spindle — lost their sacred glow.

It’s a tale of disenchantment: a cultural coming-of-age in which the protagonist wakes up from charmed sleep and, as the harsh light strikes newly awakened senses, accepts that it is time to buckle down to business, relying on self-discipline and a strong work ethic to see the way through.

In this story, people take on secular attitudes and values. They turn from community to competition. The sin of greed becomes the desirable trait of “self-interest” and the habit of devotion gives way to the quest for domination. Veneration morphs into venality. We ditch the old totems and taboos and work like crazy, trying our best to be thrifty and restrained so that we can accumulate wealth, now our chief focus. By the time we arrive at the 21st century, the neoliberal regime and its chosen institution, the global corporation, are bringing us dazzling products that promise to meet our wants and needs. The system may be rapacious and exploitive, true. We may often feel twinges of unfulfillment and uncertainty, yes. But that’s the price we pay for the goodies and convenience. The dispirited must suck it up, for, as Maggie Thatcher famously insisted, there is no alternative.

But is disenchantment really the whole story? Did human beings flip a switch and give up the psychic, moral, and spiritual longings that had been with us for millennia? Did we no longer need connection to something greater than our own bank accounts? Did we lose the feeling for something sacred and enchanted in the universe?

Possibly not. Critics of the disenchantment narrative have long noticed that if you look closely at western modernity, this ostensibly secular and rational regime, you find it pretty much teeming with magical thinking, supernatural forces, and promises of grace. Maybe the human yearning for enchantment never went away; it just got redirected. God is there, just pointing down other paths. As scholars like Max Weber have noted, capitalism is a really a religion, complete with its own rites, deities, and rituals. Money is the Great Spirit, the latest gadgets are its sacred relics, and economists, business journalists, financiers, technocrats, and managers make up the clergy. The central doctrine holds that money will flow to perform miracles in our lives if we heed the dictates of the market gods.

As the rap artist Run DMC once put it, money becomes salvation:

“Money is the key to end all your woes

Your ups and your downs, your highs and your lows

Won’t you tell me last time that love bought you clothes?

It’s like that, and that’s the way it is”

Under Mammon, we shall reach a state of blessedness in which all our desires are realized: a heaven on earth. We become gods ourselves.

All throughout the modern era, poets, dissenting scholars, writers, political radicals, and a motley assortment of ordinary apostates kept insisting that we are under the deadly spell of a false religion. Eugene McCarraher’s The Enchantments of Mammon: Capitalism as the Religion of Modernity is a magisterial account in this vein. The author sets out to explain how we came to find ourselves devoted to the jealous god Mammon, and how we might get free.

In distinction to some like-minded thinkers, McCarraher holds that capitalism is not a disenchantment, or even a reinchantment, but rather a misenchantment, a “parody or perversion of our longing for a sacramental way of being in the world.” He sees the condition peaking at beginning of the 21st century, followed by calamitous years of economic crises, political and social unrest, and now, as Ruskin scholar Jeffrey Spear and I have described, a pandemic in which the neoliberal priests demand human sacrifice to the cult of Mammon.

Here we are, many of us alienated, anxious, sick, bored, and slogging through with a suspicion that the dream of an iPhone in every pocket leaves much to be desired, and haunted by a feeling that capitalism didn’t make us gods, but turned us into monsters who treat each other horribly. Rather than bringing us to a garden of economic delights, our religion has befouled our home on Earth.

If the spell is beginning to wear thin, McCarraher thinks we should be thankful and prepare to repent and renew ourselves. But first, we need to “tell a different story about our country and its unexceptional sins.” His prophetically fired, thousand-page volume is that alternative story — not only a detailed history of the movement from an enchanted to a misenchanted world, but a condemnation of false prophets and an imaginative conjuring of possibilities for a different way of existing. This is big, heady stuff. And heartening stuff for the weary.

One Nation, Under Mammon

McCarraher begins with the advent of capitalism in the 17th century, tracing the progress of a set of ideas and values through the smoke of England’s factories and the new creed’s migration to America, where it is duly anointed by Puritans, evangelicals, and Mormons, whose founder Joseph Smith issues economic oracles. We travel on to America’s launch as a nation, when the founders dedicate the new country to the ideals of brotherhood and profit-seeking, a contradictory project embodied in Thomas Jefferson, who promotes a republic of frugal, virtuous yeoman while blowing — McCarraher doesn’t mention this point — ridiculous sums pimping out his mansion.

The tale continues through the Gilded Age, when the corporation acquires a soul in the form of “personhood” and capitalists seek to fashion a “heavenly city of business” through mechanized production. Here we find spirit and capital co-mingled, as titans of business like Cornelius Vanderbilt attend séances where the dead provide stock tips and John D. Rockefeller, Sr., the son of a traveling snake oil salesman known as “Devil Bill,” insists that “God gave me my money.”

Hallelujah!

We come along to the think tanks and college seminars of the mid-20th century, where a rising order of magician-priests, the University of Chicago-trained economists and wonks, seek to remake everything, including the state, in the image of the market. They use their best sleight-of-hand to protect Mammon from any interference from democracy while making it all look quite spontaneous. Thus, the American Century morphs into the “neoliberal Market Everlasting,” and Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand becomes the Not-So-Invisible Fist, described by Thomas Friedman, an exceptionally loyal neoliberal clergyman, in a 1999 New York Times magazine piece quoted by McCarraher:

“For globalization to work, America can’t be afraid to act like the almighty superpower that it is. The hidden hand of the market will not work without a hidden fist. McDonald’s cannot flourish without McDonnell-Douglas, the designer of the F-15, and the hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley’s technology is called the United States, Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps…”

The rest is more and more of us getting clobbered by that almighty fist.

McCarraher’s tale brings plenty of fascinating twists and turns. America produces potent witnesses against Mammon — often met with stark brutality — among Black Americans, whose initial position in the atrocious slave economy gives them profound insight into the god’s lies and ruses. There are also the failed romances of communal societies where people try but can’t ultimately escape the burden of misenchantment. And we find prescient writers, like Henry David Thoreau and Herman Melville, who see the market clearly as a god of servitude. But the Word that wins the day is that of Ralph Waldo Emerson, America’s cardboard answer to Nietzsche, who, in the guise of a “romanticism of the future,” preaches “the enchanting mendacity of power” and pronounces the cut-throat ways of capitalism as the undisputed way of the world, a view captured in a chilling line from “The Young American”: ”If one of the flock wound himself, or so much as limp, the rest eat him up incontinently.”

This gobble-gobble gospel is enthusiastically embraced by business writers, managers and libertarians like Ayn Rand, a priestess of Mammon bent on “bringing to a graceless apogee the American divinization of power that began with Emerson.” McCarraher offers an intriguing look at how American business journalism partly arises as a religious enterprise, with magazine publisher Freeman Hunt plugging a gospel of entrepreneurial divinity and the worship of technology, herding the flock towards a particular strain of misenchantment later called the “technological sublime.” The promoters of scientific management, for their part, offer a beatific vision for control freaks — a devotion to timekeeping and standardized behavior that may have partly originated in medieval monasteries.

McCarraher illustrates how we start to break down on the road to “progress.” We become split creatures who submit to calculation and control in the external world, but inside indulge in hedonistic daydreams first stoked by sentimental religion and popular novels, and later, by consumer culture and the self-help industry. We’re all wrapped up in our fantasies as Mammon’s economist-priests order the faithful to suffer any conflict or scarcity for the promise of material happiness that awaits. He points out that it was Adam Smith himself, in the Theory of Moral Sentiments, who revealed the Great Lie fed to the congregation in a description of a poor boy who, glimpsing the lifestyles of the rich and famous, becomes “enchanted” and vows to work tirelessly to fulfill his desire for luxuries – only to find out in the end that it has all been a trivial pursuit. Pitiful, but how else do you keep him in line?

The misenchantment McCarraher describes is so pervasive that it even infects dissenters, like unions that downsize their ambition from power to just a little redistribution; beatniks and hippies whose bohemian visions are swallowed up into consumer culture and corporate consciousness; or environmentalists who accommodate capitalist expansion. The Occupy Movement provides powerful anticapitalist testimony, but it looks like a lot of the “99 percent” want to “take back” the American Dream, not awaken from it. With the exception of the rising number of socialists (many of them young people), a huge chunk of the population buys into the concept of progress based on unlimited economic growth and technological development, all of it driven by expanding material wants and expectations for godlike control of life.

We are left with domineering captains of industry who pose as the stewards of humanity, like Jeff Bezos, who would like very much to rocket us all off to a technoparadise in space, where we can live happily ever after in temperature-regulated oscillating tubes.

McCarraher asks, is progress really progress if it looks like that?

But wait, you say. Doesn’t western modernity deliver some good things? We have a safety net in our old age. We have certain protections from exploitation a medieval peasant couldn’t expect. In most place other than the United States, we have access to universal health care. Yes, we do, acknowledges McCarraher. But these benefits have been brought to us by people who fought against the misenchantment, like unions, welfare states, and radical movements.

Fair enough. But what is the alternative?

The Visionary Commonwealth

McCarraher doesn’t offer an easy way out, warning that our depleted imaginations prevent us from seeing much of anything but a life of indentured servitude to capital.

Do we turn to poetry? The ecstasy of the body? Radical politics? Revolution? Spirituality? Zen sutras? Voluntary poverty? Artisanal anarchism? Do we commune with nature?

Well, maybe as long as there’s a spark of what McCarraher calls “sacramental vision,” perhaps it really doesn’t matter. In order to be alert and resist Mammon’s spell, we basically need something that posits the life of the spirit against the death culture of the market. As writer and monk Thomas Merton put it, we also need to know that the score, to grok the fact that the claims of the world are fraudulent. We need to commit ourselves to living by new values infused with affection, reverence, and spiritual adventure.

McCarraher finds the most invigorating opposition to capitalist misenchantment in the Romantic tradition. He draws sustenance from the writing of 19th century critic John Ruskin, who pronounced economics a pseudoscience and declaimed against the “Goddess of Getting on,” urging people to give up the urge to dominate and control. Though some Romantics were undoubtedly reactionary, as the author concedes, their focus on morality, the dignity of human beings, and the search for meaningful purpose is traceable in the work of dissenters ranging from Leo Tolstoy to Marx and Engels to Martin Luther King, Jr.. It shows up in the Anglo-Catholic sacramentalism of Vida Dutton Scudder, the gift-economy writing of Mary Austin, and the Personalist opposition of Dorothy Day, who rooted her challenge to industrial capitalism in Christian humanism. It appears, too, in Lewis Mumford’s opposition to death culture and the authoritarian trends in technology, and in New Left writers like Norman O. Brown, who focused on the sensuous textures and possibilities of the world. In all of these can be detected Ruskin’s dictum that “there is no wealth but life.”

McCarraher finds the visions of Romanticism to more resilient and humane than those of Marxism, and more nuanced and accurate in their assessment of human nature. He believes they provide a “language for the human magnificence we witness in the wake of devastation … a language that expresses our longings both for a sense of the world’s magnitude and for fleshly access to transcendence.” He contends that “our best hope for an imaginative and political antithesis to capitalist enchantment resides in the lineage of Romantic, sacramental radicalism.”

It’s pretty clear that his is not a secular romanticism. The author is inspired by the poetry Gerard Manley Hopkins, the calls to fellowship of Pope Francis, and Christians who have preserved the reverence for the natural word, the ideal of communion, and an understanding of exploitation as an offense against human divinity. He is partial to the idea is that we don’t need to go seeking paradise; we already live in one — a world stamped by the grandeur of God and, as Hopkins put it, the “dearest freshness deep down things.” Recognition of this wondrous vitality around us can help us to live a more fearless, vibrant life, confident of our real worth apart from the calculus of capitalism and reassured by the bounty and goodness of the world.

Well…certainly it is inspiring when Pope Francis calls the earth a shared inheritance to be enjoyed by all. But frankly, this makes it all the more galling that in his version of God’s universe, women still rank as inferior beings, unfit to control their own bodies or speak directly to the Creator. The problem is that when people get to talking about nature as bearing the watermark of its creator, that being inevitably turns out to be male, and we find ourselves ensorcelled by a misenchantment as deadly as Mammon’s creed, the cult of patriarchy, which gets noticeably little attention in McCarraher’s thousand-page book. In fact, the two misenchantments have traditionally reinforced each other: capitalism’s co-option of sacredness, for example, tends to cast women as the ever-generous and bountiful handmaidens of Mammon.

Pope Francis may chastise us that our call to “universal communion” is corrupted by a lack of trust in God, but if you are female, you could perhaps be forgiven for not trusting God. Theology has degraded women more than any other influence, and to this day, the world’s religions still conform to economist Heidi Hartmann’s definition of patriarchy as “relations between men, which have a material base, and which, though hierarchical, establish or create interdependence and solidarity among men that enable them to dominate women.”

The ideal of brotherhood often pretends to universalism, but in practice draws from the narrow experiences of powerful men. Too often, it’s just an ideal of bros.

There’s also the issue that reading messages of love and abundance in nature assumes a benevolent, anthropomorphic Creator. But it’s hard to square that with Stephen Jay Gould’s observation that there are many things on Earth that are shocking to our human moral sensibilities, such as the ichneumon fly, which lays eggs on the host’s body and paralyzes it so it can’t move as it’s slowly eaten alive. You just can’t get all Gerard-Manley-Hopkins on the ichneumon fly, I’m sorry to say. It is for this reason that feminist ecologists like Valerie Plumwood have cautioned us to see ourselves as part of nature but also to be respectful about nature’s otherness, and to avoid reading our own moral lessons from it. After all, many a theologian has looked to nature for moral inspiration and drawn terrible lessons, such as the lesser status of anyone who is not a straight white male.

Finally, there are dangerous strains of sacramental enchantment, as the global rise of Pentecostalism and strains of the far right illustrate. Not every Romantic visionary is amenable to the idea of the sort of commonwealth McCarraher would like to see. The author is clear that he doesn’t want a return to pre-modern technology or social relations, and undoubtedly he wants an evolved approach to God. But unfortunately, God is still hopelessly behind the times. Couldn’t we just ditch the word altogether?

Still, with all that said, McCarraher’s book is a highly rewarding and powerful expression of the longing for a more hospitable way of living and a potent call to orient ourselves towards our capacities as caring, creative, and convivial beings, rather than the nasty horde of hustlers Mammon insists that we are.

As Americans move toward a new administration looking to be fully aligned with the misenchantments of money and technology – witness the list of Silicon Valley tycoons set to help steer his ship of state – McCarraher’s book is a welcome wake-up call and a reminder that while we didn’t compose the narrative we live inside, we do have choices about the ending.

So thank you, Professor McCarraher, for helping us to think outside the temple.