Details of the €85bn Irish bailout have finally emerged, and no one is happy. No one now questions the scale of the losses on the balance sheets of the Irish banks; the only question is who will bear those losses. Details make clear that the answer is the Irish taxpayer, at least in the first instance.

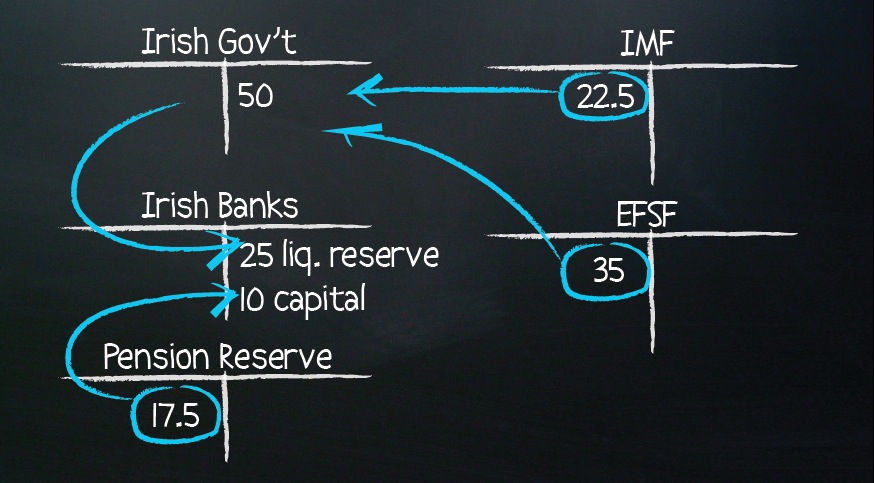

A stylized set of balance sheets make clear how it is all supposed to work. There are three main sources of funds, the European Financial Stability Fund (€35bn), the IMF (€22.5 bn), and the Irish Pension Reserve Fund (€17.5bn). There are three main uses of funds, recapitalization of the banks (€10bn), a contingent reserve for the banks (€25), and the Irish government (€50).

The important point, however, is that EFSF and IMF funds go to the government, not to the banks, so the taxpayer is on the hook for them. And of course the Pension Reserve Fund is a reserve for Irish pensions, so again the taxpayer is on the hook.

In effect, the losses of the Irish banks are being socialized, but at the level of Ireland not at the level of Europe. The senior bondholders (whether Irish, European, or other) are protected from loss, as also are the foreign firms whose corporate tax rate remains concessionary.

This is the plan for Ireland, but it is also likely the plan for Spain and Portugal. Every tub on its bottom, or rather on the bottom of the local taxpayers.

The effect, predictably enough, has been to shift concern about the financial condition of the banks to concern about the financial condition of the more peripheral European states. It is all very well to assert that all these debts must be paid by the local taxpayers; it is quite another thing to actually collect, and markets are expressing doubts on that score. If the taxpayer can’t or won’t pay, then the bondholder won’t get paid, and that prospect shows up in the price of sovereign debt today.