What is GM CEO Mary Barra’s take-home pay? (It’s more than you are being told)

In striking General Motors (GM), Ford, and Stellantis, the United Auto Workers (UAW) has put the spotlight on the enormous pay packages of these companies’ CEOs. UAW leader Shawn Fain claims that the combined average pay of the CEOs at GM, Ford, and Stellantis has increased 40% since 2019, the date of the last UAW contract with the automakers. He cites that increase in justifying his demand that his union’s members get the same raises as well over the next four years.

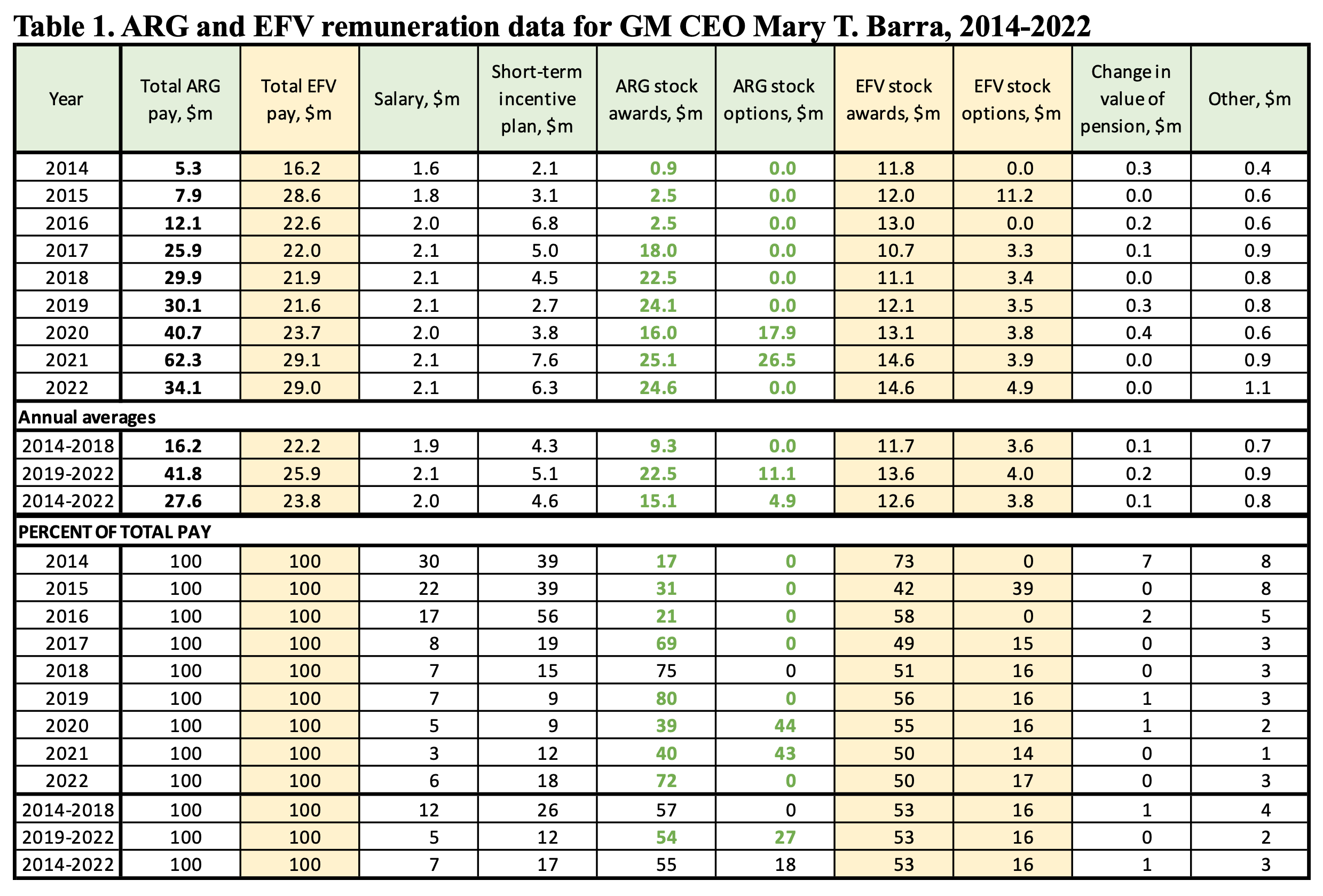

According to the UAW’s methodology, comparing 2019 and 2022, CEO pay increased by 34% at GM, 21% at Ford, and 77% at Stellantis. In both years, Mary Barra, CEO of GM, had by far the highest pay of the three top executives. According to the UAW, Barra’s compensation was $21.6 million in 2019 and $29.0 million in 2022.

In fact, Barra’s actual take-home compensation was $30.1 million in 2019 and $34.1 million in 2022, substantially higher than the UAW’s figures for those years but yielding a smaller 13% increase. Moreover, the money that Barra banked in these two years was far less than her take-home compensation of $40.7 million in 2020 and $62.3 million in 2021. Barra’s actual annual pay averaged $41.8 million over these four years, whereas the numbers used by the UAW give an average of $25.9 million.

UAW members have good reason to be outraged by CEO pay. But the situation is even worse than they think. While Fain’s demand for a UAW contract that matches the percentage increase in CEO pay is a neat rallying cry, it is problematic when one understands not only how much Barra got paid but also how she got paid. Of the $167.2 million in total compensation that Barra received in 2019-2022, $134.3 million, or 80%, was the actual realized gains (ARG) from the vesting of stock awards and the exercise of stock options, which combine to constitute Barra’s stock-based compensation (SBC).

This ARG of SBC data is not, however, included in the figure for total compensation found in the “Summary Compensation Table” (SCT) of GM’s annual proxy statements. Instead, the SCT includes formulaic numbers for the “estimated fair value” (EFV) of SBC. For stock awards, it is the number of shares granted in the current year times the grant-date price of GM’s stock. For stock options, it is the number of shares granted in the current year times the share price generated by an option-pricing model based upon the grant-date stock price.

But the supposed point of stock awards and stock options is to incentivize Barra to make decisions that increase GM’s stock price so that she reaps realized gains on the future dates when her stock awards vest or when she chooses to exercise her stock options (see Table 1). For the grant year, EFV reflects the number of shares contained in stock awards and/or stock options that may yield ARG of stock-based compensation in future years. It is ARG that measures the income that flows into Barra’s bank account when, as the name says, the gains from stock-based compensation are realized. Barra pays personal income taxes on her ARG compensation, not on her so-called EFV compensation. Indeed, it is Barra’s ARG that GM records as a compensation expense in its corporate income-tax filing.

Notes: ARG=actual realized gains; EFV=estimated fair value / Source: General Motors Form DEF 14A (proxy statement), SEC filings, 2015-2023

GM’s annual proxy statements report Barra’s ARG from SBC in a table labeled “Option Exercises and Stock Vested.” However, ARG measures are not used as components of total executive compensation in the SCT. Instead, EFV numbers are used (see Table 1). Hence, the annual total “pay” of Barra or any other senior corporate executive named on a publicly listed corporation’s proxy statement always includes the EFV numbers, which, to repeat, do not disclose what executives actually receive as money in the bank.

The automobile industry provides us with an egregious example of the difference between EFV and ARG measures of pay. Using EFV, Tesla’s SCT for 2021 reported that CEO Elon Musk received zero pay. In fact, Musk’s total compensation was $23.5 billion, comprised entirely of ARG from the exercise of 22.9 million stock options, granted in 2012. In that year, the EFV of Musk’s stock options was “only” $78 million. If, relying on the SCT in Tesla’s proxy statements, one always uses EFV figures in calculating Musk’s annual total pay, one will never record his 2021 ARG of $23.5 billion as part of his compensation history as Tesla’s CEO.

Driving stockholder value (The “fair value” pay scam)

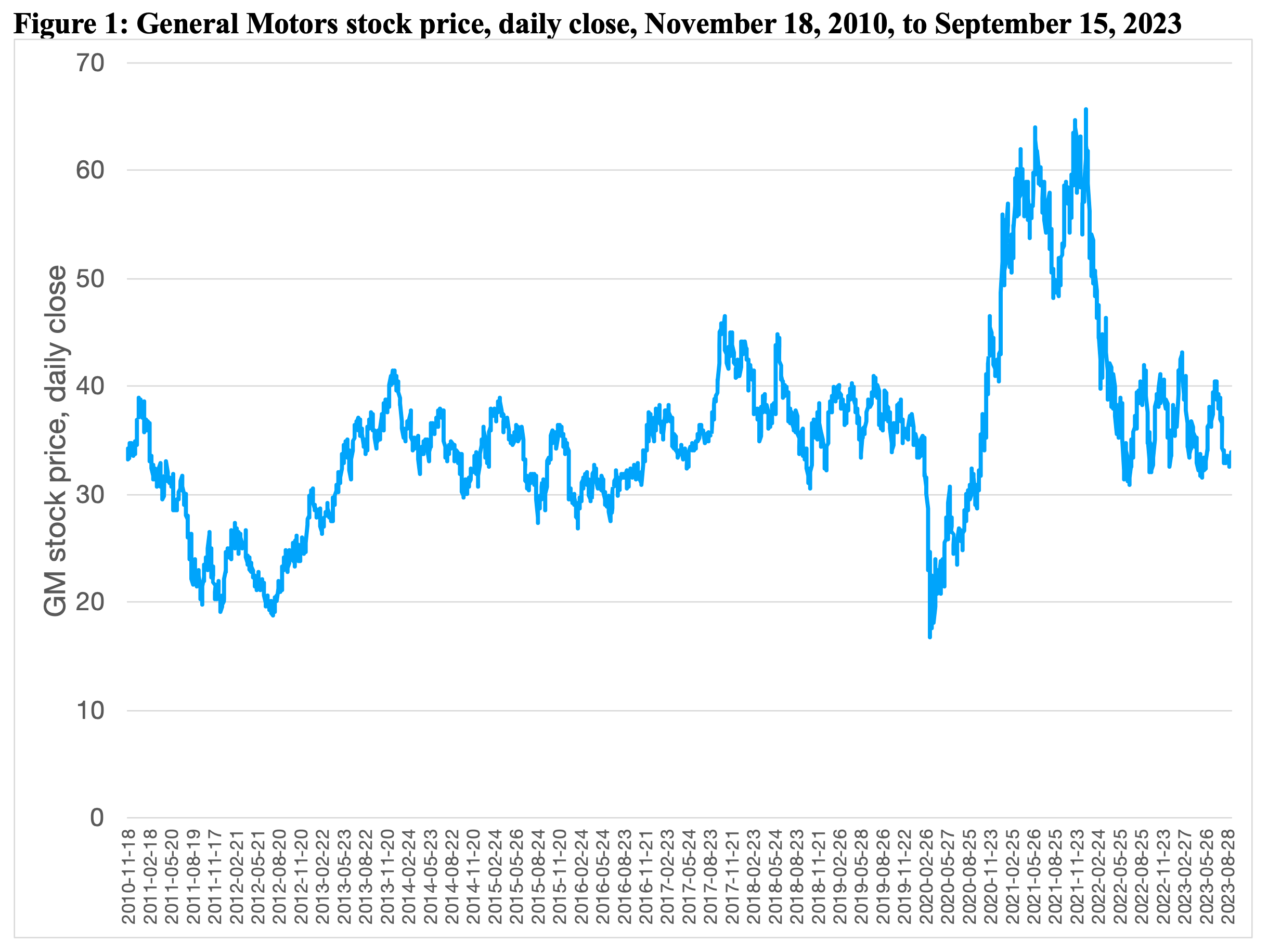

Super-inflating Barra’s compensation in 2020 and 2021 was the sale of 2,603,027 GM shares that she obtained from a one-time “Driving Stockholder Value” (DSV) stock-option grant that the GM compensation committee gave to her in 2015. Forty percent of this option grant automatically vested in February 2017, with the remaining 60% of the grant vesting in equal 20% installments in February 2018, 2019, and 2020, provided GM met or exceeded the median “total shareholder return” (TSR)—the sum of stock-price yield and dividend yield—of a selected group of global automobile companies. Although her options would not expire until 2025, Barra elected to exercise all 2,603,027 of the shares in the grant in November 2020 and March 2021, when, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, GM’s stock price was surging (see Figure 1).

Source: Yahoo Finance, historical prices

The ARG bonanza from exercising the DSV options totaled $44.4 million over the two years. In the EFV stock-options column shown in Table 1, Barra’s grant-date DSV option “pay” was reportedly $11.2 million in 2015. In that year the GM compensation committee decided that “driving stockholder value” required giving big-bang incentives to the CEO and 300 other senior executives to take actions to increase TSR. Barra’s insider-sales disclosures reveal that she sold every single one of those 2,603,027 shares immediately after she exercised them to lock in her realized gains (note that, on the $44.4 million, she would have paid taxes on the exercise date at the ordinary rate regardless of whether she sold the shares upon exercising her options or decided to hold on to them).

The absurdity of using EFV as the measure of an executive’s stock-based compensation becomes even clearer when, as illustrations, we compare Barra’s recorded EFV for stock options in 2020 and 2021 and her stock awards in 2021 and 2022 (see Table 1). Her EFVs of stock options were $3.75 million in 2020 and $3.93 million in 2021. The board’s compensation committee chose these numbers as the “target” EFV stock-option “pay” and then divided each target figure by a stock-option pricing formula, which included GM’s grant-date stock price, to derive the number of shares included in the option grant.

For 2020, the number of shares was 744,048 at a grant-date stock price of $35.49, while for 2021 (with a slightly higher EFV target than 2020), the number of shares was only 194,637 at a grant-date stock price of $52.16. In other words, comparing the stock-option grants in the two years, GM rewarded Barra with far more shares when GM’s stock price was lower—or, alternatively stated, the company provided Barra with fewer shares for her “performance” when GM’s stock price was higher.

The same result holds when we compare Barra’s stock awards in 2021 and 2022, in which the target EFVs were almost identical at $14.58 million and $14.63 million, respectively. In 2021, with a grant-date price of $64.39, the number of shares in the award was 226,467 with the possibility of an additional 226,467 shares if GM met targets for return on invested capital (ROIC) and TSR metrics. In 2022, with a lower grant-date price of $50.97, the number of shares in the award increased to 286,926 with the possibility of up to an additional 286,926 shares, with the precise amount of extra shares dependent on the achievement of ROIC, TSR, and EV transition metrics. That is, the CEO received 27% more shares in her stock award in 2022 than in 2021, even as GM’s stock price on the respective grant dates fell by 21%.

In an interview with CNN, Barra sought to justify her pay package by pointing out that “92% of my compensation is based on the performance of the company.” She could have added that 76% of that “performance pay” was the EFV of stock awards and stock options. Yet, as we have just explained, the number of new shares that Barra obtained from the awards and option grants on which she could potentially realize future income was inversely related to the performance of GM’s stock price. That’s nice “performance pay” if you can get it!

The construction and components of Mary Barra’s pay are not unique to GM; they are typical of the compensation practices of publicly listed US business corporations. Quite apart from our own critique of stock price as a measure of corporate “performance,” the absurdity of the EFV measures of SBC is that they reward negative stock-price movements. Specifically (as we discuss below), ARG creates strong incentives for senior executives to allocate corporate resources to stock buybacks.

The use of the EFV measure proliferates because the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in collaboration with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) used faulty economics in mandating the expensing of stock-based compensation on corporate financial statements in 2006, instructing companies to insert the EFV pay data into the SCT. Now, almost everybody uses the EFV data (often citing Equilar, a consulting company that bills itself as “the trusted source for executive intelligence”), without independent analysis of how to measure executive pay. In addressing the issue of executive compensation, unions, the media, consultants, and think tanks, not to mention the FASB and the SEC, should stop using estimated fair value numbers. Actual realized gains are the only accurate measure of the value of the stock-based components of executive pay.

Why does it matter? Four “Barra pay” takeaways for the UAW campaign

The UAW is engaged in a historic strike against the established US automakers. The union is trying to reverse its members’ backsliding incomes while ensuring that the car companies will employ union labor in the transition to electric vehicles (EVs). As an integral part of their struggle, the UAW leadership should denounce and seek to stem the explosion of CEO pay. In support of the UAW’s confrontation with GM, Ford, and Stellantis, there are four main takeaways from our analysis of Mary Barra’s actual realized gains compensation in comparison with the meaningless, and indeed misleading, “fair value” estimates.

The UAW leadership should 1) condemn the scam of stock-based pay, 2) demand that executive pay reward employment stability (not stock-price volatility), 3) justify worker pay increases by their contributions to corporate revenues and profits, and 4) attack predatory value extraction, starting with calling for a ban on stock buybacks. We discuss each of these takeaways, continuing to highlight the case of GM.

1. Condemn the scam of stock-based pay

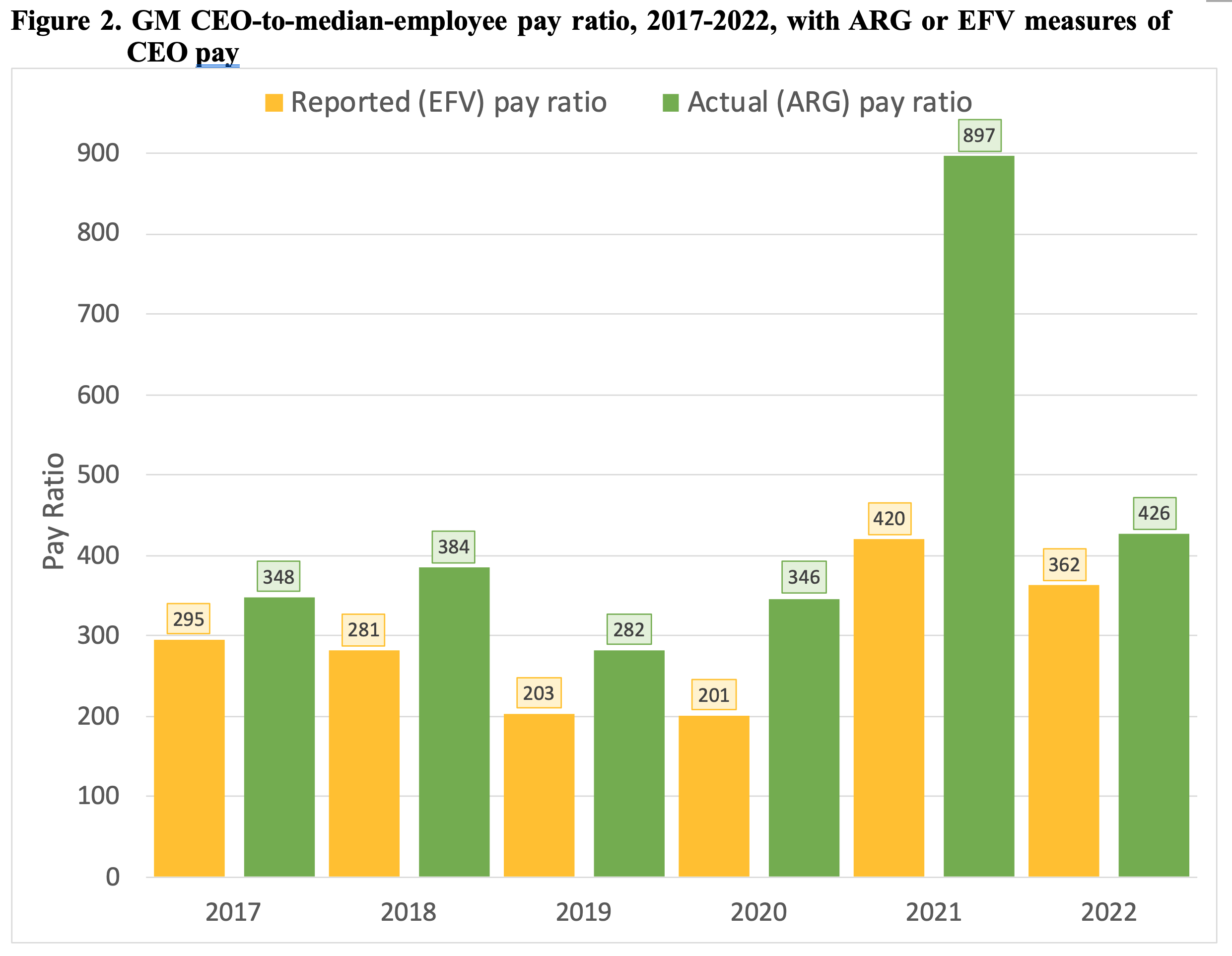

One obvious implication of our focus on ARG compensation is that when the CEO realizes gains from a rising stock price, the actual CEO-to-median-employee pay ratio is higher than the one that a company discloses. Mandated by the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, the pay ratio that each US company is required to disclose uses EFV measures of executive compensation.

Figure 2 compares GM’s pay ratio from 2017 to 2022, using the ARG and EFV measures of CEO pay. The ARG ratios are higher than the EFV ratios in every year. An unweighted average of the six years of pay-ratio data yields an ARG ratio of 447:1 versus an EFV ratio of 294:1.

Source: General Motors Form DEF 14A (proxy statement), SEC filings, 2018-2023

Beyond informing its members of the proper metric of pay inequality, the UAW’s recognition of the overwhelming importance of the stock-based components of exploding CEO pay, especially when measured correctly, is a necessary foundation for questioning why senior executives are so lavishly rewarded by the company’s stock-price performance. More fundamentally, union leaders (and business journalists) should understand the drivers of the stock-price movements that enable senior executives, along with Wall Street bankers and hedge-fund managers, to extract value for themselves that far exceeds their contributions (if any) to value creation. It is a phenomenon that we call “predatory value extraction.”

2. Demand that executive pay reward employment stability (not stock-price volatility)

Our analysis of the correct measure of CEO compensation renders meaningless the UAW’s use of a purported 40% increase in CEO pay as a justification for a 40% increase in worker pay. Armed with the knowledge of how CEO pay is determined and properly measured, union leaders should call into question the legitimacy of senior-executive multi-component compensation schemes. With an understanding of the drivers of a company’s stock price, union leaders can argue for the redesign of senior executive pay so that the interests of the CEO are aligned with those of other company employees rather than with the interests of the company’s shareholders.

Our nonprofit organization, the Academic-Industry Research Network, has produced a body of research on the functions and operation of the stock market through which we identify the three drivers of a company’s stock price: innovation, speculation, and manipulation. When, through the contributions of the skills and efforts of its employees, a publicly listed company generates a higher-quality, lower-cost good or service, the profits that accrue from the sale of this innovative product lead stock-market traders to bid up the price of the company’s stock. At some point, however, speculation takes over from innovation as the driver of the stock price increase as some naïve traders assume that the upward momentum will persist while more sophisticated traders assume that some “greater fool” will be ready to buy the overpriced stock. Sooner or later, the stock-price bubble bursts, and those traders with the power to do so turn to manipulation to seek to restore and sustain stock-price increases.

Senior corporate executives with their ample stock-based compensation often reap their realized gains by being sophisticated traders with the power (including insider information) to take actions to manipulate their company’s stock price. The most obvious way in which they engage in this manipulation is by allocating corporate cash to open-market repurchases of the company’s own outstanding shares, aka “stock buybacks.” The CEO and CFO as well as other senior executives who are “in-the-know” about when buybacks are being done can realize gains by timing the selling of shares acquired from their awards and options.

In our dissection of EFV, we have identified one mechanism by which senior executive pay is continuously ratcheted up. Given targeted dollar amounts for annual EFV awards and options, a fall in the company’s stock price results in the granting of more shares at the lower grant-date prices. As a result, for a given subsequent increase in the company’s stock price (whether driven by innovation, speculation, or manipulation), there are more realized gains from the vesting of awards or the exercise of options.

This inflation of ARG compensation (about which every executive recipient is completely aware) suggests to the board’s compensation committee and the consultants whom they hire that perhaps the targeted dollar amounts of EFV awards and options should be set higher than previously. It is also well-known among compensation experts that directors and their consultants justify increases in their executives’ compensation by adopting the pay targets and metrics of the higher-paid executives at selected “peer group” companies.

As, in the name of “maximizing shareholder value” (MSV), executive pay has been ratcheted up, for decades, the wages of US workers have been ratcheted down. Like other senior executives, Mary Barra’s take-home pay benefits from stock-market volatility and MSV voracity. As corporate metrics for the compensation of senior auto executives, the UAW should demand higher pay for union workers and stable employment opportunities in the EV transition.

3. Justify worker pay increases by their contributions to corporate revenues and profits

The UAW’s use of CEO pay increases as a justification for UAW member pay raises has received lots of media attention, and it may have helped to rally the troops to support the current strike. In our view, however, it is an ill-conceived strategy. Even when measured correctly, the CEO pay increases are subject to too much variability across different companies and are too sensitive to the calculation’s start and end dates to serve as a benchmark for worker pay increases.

If the UAW had used total ARG compensation to measure the percentage increase in CEO pay at GM, Ford, and Stellantis from 2019 to 2022, it would have found that the combined pay increase was 49% from 2019 to 2022, but with disparate rates of 13% at GM, 153% at Ford, and 71% at Stellantis. Given the volatility of year-to-year executive pay using the correct ARG measure, these rates would have been very different for each company choosing a different four-year period.

For example, if the comparison had been between Barra’s total ARG pay in 2018 and 2021, the increase would have been 108%. If the UAW contract had been up for renegotiation last year rather than this year, would the union have demanded a doubling of its members’ pay over the next four years? For reasons of both measurement and variation, therefore, it was not a good idea for the UAW to seize upon a percentage increase in combined total EFV compensation as a justification for demanding the same pay hike in their contract negotiations.

The larger issue, however, is that this demand lends legitimacy to executive pay as a benchmark of GM’s affordable pay increases for UAW members, when in fact even the calculation using the correct ARG numbers for CEO pay has nothing to do with affordability. To the contrary, the UAW should be challenging the legitimacy of CEO pay and the destructive MSV ideology that underpins it. The best way to mount that challenge is by showing that it is workers, not shareholders, who have delivered GM’s revenues and profits.

It is an easy case to make for GM, which has been highly profitable since 2010, after the UAW and the US and Canadian governments brought the company out of bankruptcy in June-July 2009. During the bailout, finance from equity investors was nowhere to be found. Instead, US taxpayers put up $49.5 billion in rescue funding, and Canadian taxpayers pitched in another $10.9 billion, enabling GM to emerge from bankruptcy after just 40 days. In 2010, the “New GM” did one of the largest public offerings in history, with share sales to the public of $23.1 billion by the US and Canadian governments as well as the UAW through its Voluntary Employee Beneficiary Association (VEBA) Trust.

None of the funds raised by listing GM’s common shares on the New York Stock Exchange went to GM for investment in productive capabilities or any other purpose. GM’s only funding from shareholders was a preferred stock issue of $4.9 billion, of which $2.1 billion was used to repurchase part of a previous preferred stock issue to the US government and the remainder to help fund US hourly and salary pension plans.

The UAW shouldered a substantial burden of the bailout, enabling GM to reduce labor costs by $11 billion. There were 21,000 layoffs; a wage freeze for current workers; a halved wage of $14 per hour for non-core new hires; elimination of a funding program for unemployed workers; a no-strike agreement until 2015; and the VEBA that shifted liability for UAW retiree healthcare and pension benefits from GM to the UAW, saving the company an estimated $3 billion per year. This cost-cutting enabled GM to return to profitability, with annual net income averaging $6.7 billion from 2010 through 2013.

When, in January 2014, Mary Barra was named GM CEO, she had only US and Canadian taxpayers and UAW workers to thank for the fact that the company even existed to offer her the job. Common shareholders, in whose interests GM’s senior executives claim the company should be run, have had absolutely nothing to do with GM’s productivity and profits over the past 14 years.

4. Attack predatory value extraction, starting with calling for a ban on stock buybacks

Over the course of her nine years as CEO, through 2022, Mary Barra has raked in $248.3 million in total ARG compensation, of which $180.7 million, or 73.0%, has been realized gains from stock awards and stock options. As we have seen, $44.4 million of her compensation came from the “Driving Stockholder Value” stock-option grant. According to the GM 2016 proxy statement, on July 18, 2015, the compensation committee bestowed the grant on Barra and other senior executives in part “for agreeing to non-compete and non-solicitation terms with the Company.”

In other words, Barra, whose father had worked for GM for 39 years as a tool-and-die maker and who herself had joined GM at the age of 18, earning a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from General Motors Institute in 1985, was 30 years later given options that were eventually worth tens of millions of dollars on condition that she remain as GM’s CEO for the next four and a half years.

As stated in GM’s 2016 proxy statement, the “benefit to shareholders” of the 2015 stock-option grant would come from “senior leaders aligned to the interests of shareholders,” “increased focus on GM stock price,” and “stable leadership.” Precipitating this very tangible incentive for Barra and her C-suite team to devote their time, energy, and, as we shall see, GM’s cash to “maximizing shareholder value” was a visit to Barra’s office in January 2015 by a corporate predator named Harry J. Wilson, fronting for four hedge funds.

Wilson was no stranger to GM and the US automobile industry. With Wall Street experience, in March 2009, Wilson was hired by the Presidential Task Force of the Auto Industry as one of two senior advisors on auto issues at the Treasury Department. Wilson was the one who insisted that, in funding the GM bailout, the US government accept GM stock rather than bonds. If the US Treasury had been a GM bondholder, US taxpayers would have been in a far stronger position to recoup their investment in the New GM.

When GM came out of bankruptcy in 2009, did its public offering in 2010, and generated profits thereafter, the right-wing meme, echoed by Wall Street, was that “Government Motors” should dispose of its shares immediately. By the time the US Treasury sold its last shares in December 2013, US taxpayers had suffered a loss of $11.2 billion. The exit of “Government Motors” opened the door for Wilson and his hedge-fund backers, with 2.1% of GM’s outstanding stock, to march into GM and demand that the company hand over all its “free cash flow” to shareholders.

At their meeting in January 2015, Wilson informed Barra that the hedge funds wanted GM to do $8 billion in buybacks and, as their representative, appoint him to a seat on the GM board. After negotiations that sought to avoid a proxy fight, GM got the hedge funds to agree to a $5-billion buyback and no board seat for Wilson. He called the $5-billion buyback a “win-win outcome.” But for US taxpayers and GM’s workers who had brought the company out of bankruptcy and restored its profitability, the buybacks amounted to a major loss.

The only purpose of the buybacks, done as open-market repurchases, was to give manipulative boosts to GM’s stock price. Prime beneficiaries of the buybacks were Wilson and his hedge-fund activists, who could seek to time the selling of their GM shares to realize stock-price gains. Given the overt “shareholder value” objectives of the Driving Stockholder Value option grant as well as its timing (July 2015), it seems clear that its purpose was to align the interests of GM’s senior executives with the interests of Wilson and his hedge fund sharesellers by giving the executives a special opportunity to participate in the “win-win” bargain by having their own ARG of SBC inflated by the buyback manipulation.

The prime losers were UAW workers, to whom the corporate cash wasted on buybacks could have been allocated as wages and benefits, restoring to them some of what they had lost in making possible the profitability of the New GM, and to ensure new jobs for them in the EV transition. However, it appears that the buybacks that GM did to appease Wilson and the hedge funds delayed and blunted the company’s investment in the transition to EVs. Shareholder activists objected to GM’s investment in high-risk projects such as the battery EV Bolt and the hybrid EV Volt. Moreover, the $5 billion in buybacks that GM’s board authorized and its senior executives carried out in 2015 and 2016 to get Wilson off their backs was not the end of it.

In order to continue juicing GM’s stock, in January 2016, Barra and her board authorized an additional $4 billion dollars in buybacks. Then, beginning in September 2016, another corporate predator, David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital, appeared on the scene. Einhorn demanded that GM create a new class of “Dividend Shares,” which, according to GM’s 2017 proxy statement, “would be senior to the existing common stock and carry a fixed cumulative dividend as well as rights to board representation if dividends were in arrears.” GM’s board flatly rejected Einhorn’s proposal, but authorized another $5 billion in buybacks in January 2017, in part to get Einhorn to sell his shares and leave them alone.

The actual stock buybacks done under the buyback authorizations that began in 2015 and concluded in the first quarter of 2018 amounted to $11.3 billion. The buybacks largely succeeded in keeping the shareholder activists at bay, while providing an opportunity for Barra and her colleagues to boost their own stock-based pay.

Meanwhile, having slashed employment and R&D, GM had to get serious about the EV transition before it fell too far behind. The company did no buybacks from the second quarter of 2018 through the second quarter of 2022. Then, flush with profits reaped during the pandemic—$10.0 billion in 2021 and $9.9 billion in 2022—the GM board resumed its stock buybacks in the third quarter of 2022, carrying out $3.5 billion through the first half of 2023. To help fund buybacks, GM is “maximizing profits” by seeking to cut costs by, for example, completing buyouts of thousands of employees ahead of possible layoffs.

The UAW has sharply criticized GM’s buybacks during its strike campaign. In a recent op-ed, UAW vice president Mike Booth said that buybacks are tantamount to “lavishing Wall Street with the results of our labor.” A GM spokesperson responded by saying that “we’ve used buybacks and dividends like a great many other companies, to return capital to our owners after we’ve invested in growth.” The UAW should be asking how a company like GM can “return capital” to “owners” who never gave them any funding. It was workers and taxpayers who invested in the New GM. The so-called “owners” have merely purchased shares already outstanding, including those acquired from the US Treasury and the UAW in the years before Wilson, Einhorn and other hedge-fund predators laid claim to GM’s profits.

The UAW, along with other labor unions, should be demanding that Congress ban stock buybacks done as open-market repurchases. In lobbying for this change, the UAW could find support from President Joe Biden. When he was vice president, Biden was an ardent critic of stock buybacks and the executive-pay packages that incentivize and benefit from them.

Then there is Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY). In an August 2022 press conference on the Inflation Reduction Act, Schumer declared: “I hate stock buybacks. I think they are one of the most self-serving things that corporate America does. Instead of investing in workers and in training and in research and in equipment, they don’t do a thing to make their company better and they artificially raise the stock price by just reducing the number of shares. They’re despicable. I’d like to abolish them.”

Indeed, the Reward Work Act, introduced in the Senate by Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) in 2018 and 2019, and most recently in the House by Jesús “Chuy” García (IL-04), Ro Khanna (CA-17), and Val Hoyle (OR-04), would expose corporate executives who do large-scale buybacks to stock-price manipulation charges, while mandating that employees elect one-third of the directors of publicly listed corporations.

At GM, the first order of business for those employee board members would be to make rising living standards of the company’s workers and the creation of union jobs in the EV transition the fundamental metrics in determining the realized gains in Mary Barra’s pay.

***

Matt Hopkins is a senior research associate at, and William Lazonick is president of, the Academic-Industry Research Network. They gratefully acknowledge funding for the research underpinning this article from the Institute for New Economic Thinking and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Program on Innovation, Equity & the Future of Prosperity, and valuable comments on a previous draft by Thomas Ferguson and Ken Jacobson.