Regardless of what Trump says, the economic pain of the pandemic isn’t going anywhere

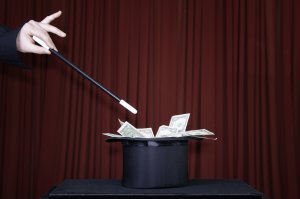

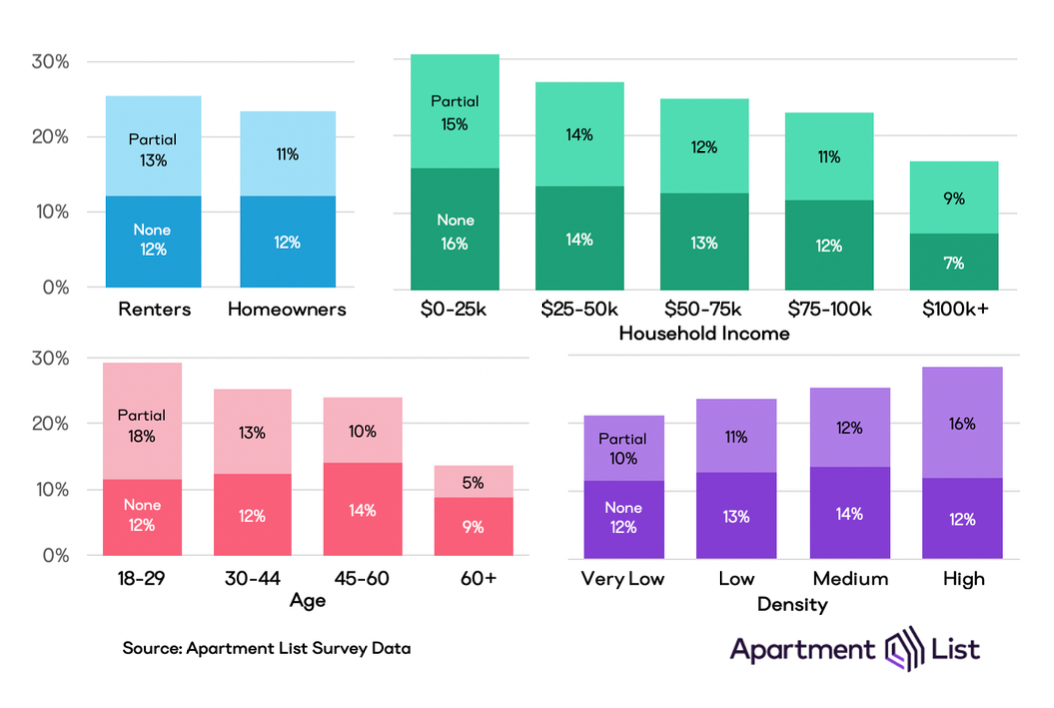

Whether statistically significant or not, in some quarters a little good news goes a long way. The news Mr. Trump might have in mind is heralded in Figures 1 and 2.

Although some have described these figures as ”turning a corner,” the improvements mainly reflect the reopening of employment opportunities in some states. It does not tell us much about the financial chaos that may still lie in store.

Financial chaos threatens to occur when the economic value of one or more important categories of assets falls sharply and suddenly. A massive price drop incentivizes holders of the affected assets to act to unload—if not the assets themselves—at least their personal exposure to the losses the price collapse implies.

An obvious purpose of having a bank-focused financial safety net is to blunt the force of a burgeoning financial panic by smoothing and softening the immediate impact of a severe price fall as its consequences churn across the world’s financial markets. The existence of a sturdy government safety net assures customers that they can’t and won’t be made to absorb the bulk of crisis-driven losses directly and immediately. But the net has deeper purposes as well. By reducing financial institutions’ exposure to disorderly customer runs, the existence of a safety net allows bankers (if that is their bent) to take on more productive (metaphorically more challenging) loans and investments. It does this by assuring managers that if their firm were to suffer a potentially ruinous run of losses, authorities are prepared to grant them time to see whether they can find a way to repair their insolvency. For some firms though, the gift of time threatens to become endless.

Fatally damaged firms whose continued existence depends entirely on supervisory forbearance and safety-net guarantees can be likened to horror-film “zombies.” This characterization is appropriate for at least two reasons. First, without the magic of sustained government support, insolvent banks could be made to settle either into a grave of corporate bankruptcy or be restored to health by the miracle of recapitalization. Second and more importantly, because with stockholders having little reason to fear further losses, zombie managers are incentivized to follow destructive go-for-broke portfolio strategies whose present value may be strongly negative. The odds that regulatory forbearance will allow an insolvent firm to operate as a zombie increase with its asset size, balance-sheet complexity, and political clout. Particularly large and powerful financial firms are said to be “too big to fail.”

To soften and delay the adverse financial consequences of the losses generated by the current virus-driven crisis, Congress and Fed officials have invented a host of short-term programs aimed at supplying temporary liquidity on favorable terms directly to banks and to their household and business customers. Moreover, zombie institutions in other countries are receiving implicitly subsidized loans from the Federal Reserve System in ways too complex to describe here.

The subsidies fill in a small part of each zombie’s loss-induced capital shortfall, but the liquidity the loans provide encourages zombie managers to gamble recklessly for resurrection. Well-publicized relaxations in the enforcement of capital and accounting standards indicate that regulators are willing to gamble alongside them.

To show some sympathy for the households and businesses that are unwittingly backing these gambles, the Fed, the Small Business Administration, and the US Treasury have been asked to administer some remarkably re-distributional funding schemes. The most imaginative of these schemes are the Paycheck Protection Program which is ostensibly aimed at protecting ordinary households by subsidizing small businesses that continue to pay their employees during the Pandemic and the Main Street Lending Program which is said to be aimed at medium-sized businesses. Loopholes in per-establishment size limits set by the second program and a similar program called the Small Business Debt Relief Program let most of the funds be captured by sophisticatedly well-lawyered big businesses that operate separate facilities in many locations. A second round of debt relief was better-targeted, but in practice, the idea of what is a “small” or “medium-sized” business remains very plastic.

It is widely understood that, although the cute names assigned to these programs may help officials running for re-election this fall, the subsidies conveyed by these schemes are too small and too short-lived to make much difference to recipients’ welfare in the long run. Unfortunately, the long run is where crisis survivors will have to live. Precisely because immediate problems are being smoothed over, the most-painful economic consequences of the Covid crisis have yet to make themselves felt. The most important of these consequences is the massive adjustments that will have to take place both in the country’s and in the world’s several trillion-dollar travel, tourism, real-estate, and real-estate finance sectors. In the US, the titles to much of the country’s cruise-ships, office complexes, and shopping centers may end up in the hands of the Federal Reserve and various hedge funds and private equity firms that have precious little experience in property management.

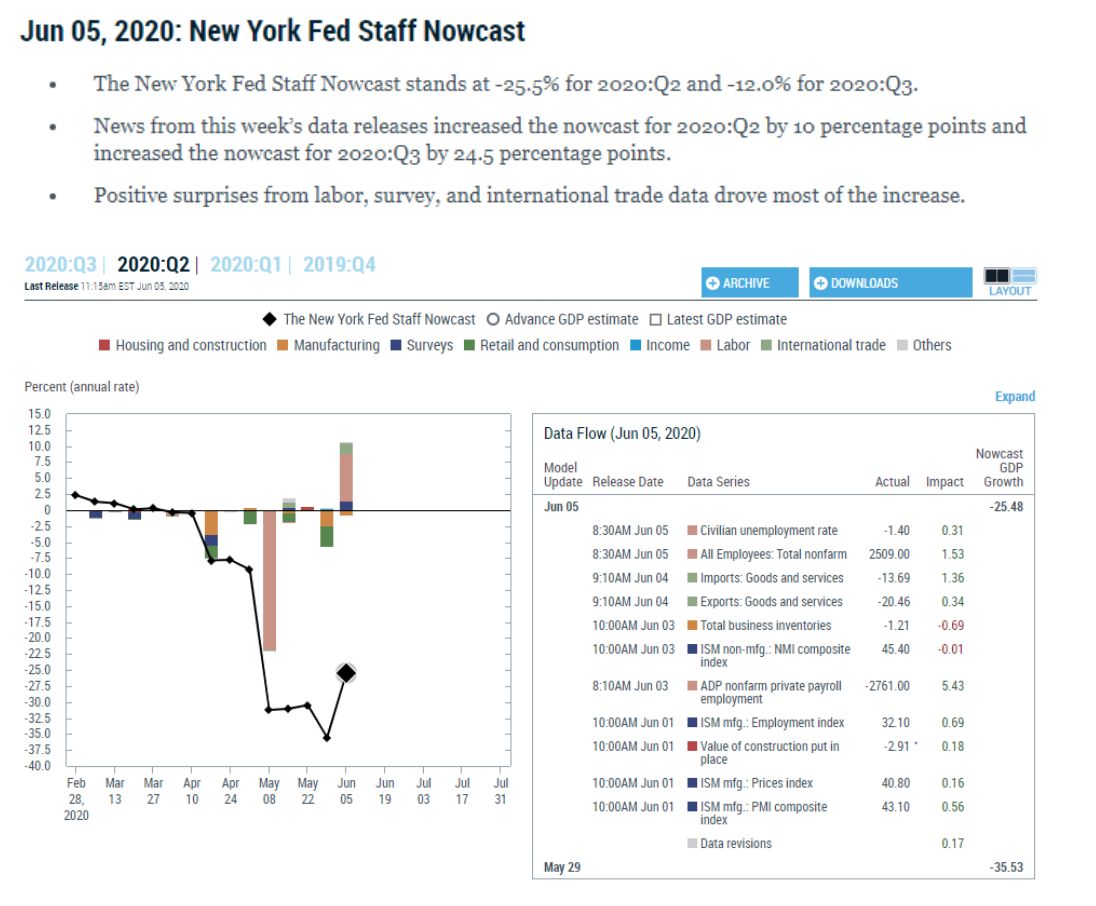

Loans and securities backed by ships, airplanes and real-estate collateral are a huge part of modern financial systems. For good reasons, interest, rent and mortgage payments are increasingly not being made by individual business and household occupants. Figure 3 shows that, even as early as April, 24 percent of apartment dwellers were not able to pay their full rents.

When payments are not made as due, delinquencies are not immediately registered. Often, the grace period is 60 days. But when grace periods expire, lenders and landlords have only two options: taking possession of the property (or collateral) or easing contract terms. Exercising these options generates uncertainty, takes additional time, and reduces the cash flows that existing contracts and properties can generate going forward.

In the wake of the indelible economic damage the pandemic is causing, a lasting contracting equilibrium in the real-estate sector requires the rents and mortgage payments implied by pre-existing contracts to be renegotiated sharply downward. The long-lasting effects of the virus on opportunities to travel and work from home will eventually make it clear that the equilibrium value and size of various commercial real-estate holdings have been permanently reduced. The glut of commercial properties (especially hotels and shopping centers) will reduce land values all around. Agreeing to tear down commercial buildings and repurposing the land on which they sit is a time-consuming business. Far from undergoing a V-shaped recovery, travel, real estate and real-estate finance will remain depressed sectors for whatever time the recontracting and loss-allocation processes take.

Sooner or later, direct and indirect mortgage lenders and tax collectors at every level of government must face the pain of these adjustments. State and local governments are deeply vulnerable. Targeting an increased flow of liquidity from the taxpayer-owned Federal Reserve System to benefit selected firms and investors in the travel, real-estate and state-and-local sector can delay and redistribute some of this pain across the population. But the pain can be postponed for only so long. We should not kid ourselves. It is going to take a good deal of time for the pain to go away.

Figure 1 Note: Readings below 50 indicate falling employment. Source: FactSet

Figure 2: Latest Nowcasting Report Source: New York Fed, based on data accessed through Haver Analytics. Notes: The nowcast for a reference quarter starts about one month before the quarter begins; updating stops about one month after the quarter closes. Colored bars reflect the impact of each broad category of data on the nowcast; the impact of specific data releases is shown in the accompanying table. For more information, please read the accompanying Liberty Street Economics post: Historical Reconstruction of the New York Fed Staff Nowcast, 2002-15.

Figure 3: Many Americans Could Not Afford Their Full Housing Costs in April The percentage who either made no payment or only a partial payment