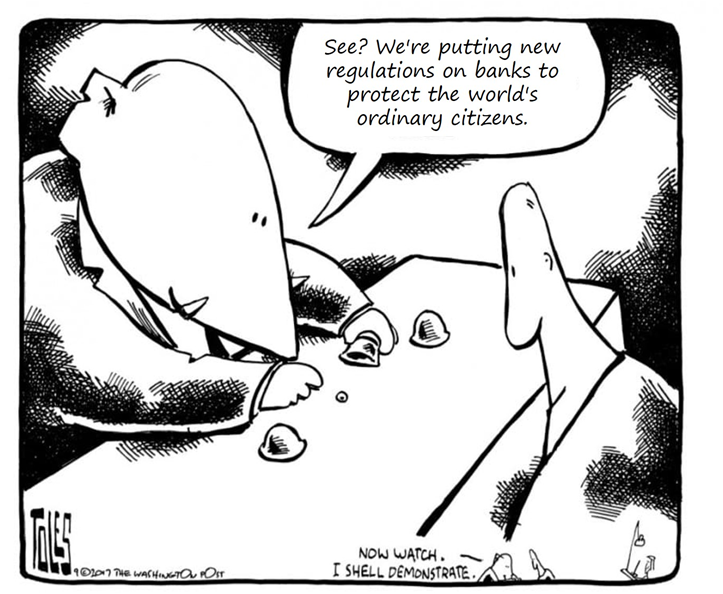

Ten years after the crisis, financial regulation leaves taxpayers holding the bag for banks’ safety net.

Regulation is best understood as a dynamic game of action and response, in which either regulators or regulatees may make a move at any time. In this game, regulatees tend to make more moves in pursuit of safety-net subsidies than regulators can or do make to stop them. Moreover, regulatee moves tend to be faster and more creative, and to have less-transparent consequences than the moves that regulators make.

In modern times, banking crises have occurred when managers pursued concentrated risks that made their institutions increasingly vulnerable, but generated a series of substantial and long-lasting safety-net subsidies until things finally went south. As I explore in my new INET working paper, such subsidies can prove long-lasting because the regulatory cultures of almost every country in the world today embrace—in one form or another—three strategic elements:

- Politically-Directed Subsidies to Selected Borrowers: The policy framework either explicitly requires—or implicitly rewards—institutions for making credit available to favored classes of borrowers at a subsidized interest rate. In recent crises, subsidized loans to homeowners played this role. However, the next crisis may feature loans to current and former students, pension funds, and state and local entities;

- Subsidies to Bank Risk-Taking: The policy framework commits government officials to offer on subsidized terms explicit and/or implicit (i.e., conjectural) guarantees of repayment to banks’ depositors and other kinds of counterparties engaging in complex forms of bank deal making;

- Defective Monitoring and Control of the Subsidies: The contracting and accounting frameworks used by banks and government officials leave no paper trail. They are careful not to make anyone directly accountable for reporting or controlling the size of these subsidies in a conscientious or timely fashion.

Taken together, the first two elements of the subsidization strategy invite commercial and investment banks to use the safety net to extract wealth surreptitiously from ordinary taxpayers. To keep subsidy-generating leverage high, the bulk of the subsidies banks receive are promptly paid out to top managers and to shareholders in the form of dividends and share repurchases. The rest is shifted forward and backward: mostly to large creditors and politically favored borrowers, but a few dollars might be reserved for like-minded academic researchers and community groups.

Favored borrowers are primarily blocs of voters (such as would-be homeowners) regularly courted by candidates for political office and traditional sources of outsized campaign support (such as bankers, landlords, builders, and realtors). Ferguson, Jorgensen, and Chen (2017) define a comprehensive concept of the “spectrum of political money” that captures a number of indirect and subtle ways that bankers (especially) put money into a politician’s pocket or election campaign. The direct ways include director’s and speaking fees, book contracts, jobs for family members, and stock tips, plus of course campaign contributions. Indirect channels comprise threatening to support an opponents’ campaign or laundering donations through law firms, charitable foundations, think tanks, community groups, and public-relations firms.

The third piece of the framework minimizes regulators’ exposure to blame when things go wrong. Gaps in the reporting system make it all but impossible for outsiders—particularly the press—to hold supervisors culpable for violating their ethical duties. These gaps prevent outsiders from understanding—let alone monitoring—the true costs and risks generated by the first two strategies. Few politicians and regulators want to subject the intersectoral flow of net regulatory benefits to informed and timely debate.

This weakness in accountability exists because the press is often content with regurgitating the content of agency press releases and because accounting systems do not report the value of regulatory benefits as a separate item for banks and other parties that receive them. In modern accounting systems, the capitalized value of regulatory subsidies is treated instead as an intangible source of value that, if booked at all (as it usually is in acquisitions), is not differentiated from other elements of what is called an acquired bank’s “franchise value.”

Of course, some of the subsidy is offset by tangible losses that politically influenced loans eventually force onto bank balance sheets and income statements. Although officials resist the idea, creating an enforceable obligation for regulators to estimate the ebb and flow of the dual subsidies in transparent and reproducible ways would be a useful first step in getting them under control. This would make it easier for watchdog organizations in the private sector to force authorities to explain whether and how these subsidies benefit taxpayers.

But Hasn’t the Dodd-Frank Act Changed All This?

The Dodd-Frank Act (DFA) is best understood as a collection of policy measures designed to weave its way respectfully through different industry lobbyists’ self-absolving alternative theories of the crisis to incorporate a (sometimes lame) treatment of the forces featured in each of them. What I find ironic in this massive and allegedly comprehensive legislation is that the particular problems that the banks’ testimony stressed all point to the interaction of the pair of implicit subsidies that my narrative highlights.

These subsidies are hidden in the systems used: (1) to finance housing investments on the one hand, and (2) to finance payouts from the US financial safety net on the other. In turn, the norms that make these subsidies durable are rooted in a generalized breakdown in professional ethics that the DFA does not treat at all. The professions of government service, accounting, financial management, credit rating, mortgage banking, derivatives broker-dealer making, and government regulation all have explicit or implicit codes of practice that (wink, wink) members of the profession are expected to follow to prevent client, user, or societal abuse and to preserve the integrity of that profession. In some countries and professions (especially medicine), violations of particular standards that impose predictable harm on other parties become a matter for law enforcement. So (I believe) it should be in finance.

Focusing Only on Bank Capital is a Loser’s Game

It is fiendishly difficult for incentive-conflicted leaders of regulatory agencies to control firms that capital markets perceive to be macroeconomically, politically, or administratively too difficult to close and unwind. For such megabanks, the Basel approach of setting capital requirements only against what have become well-understood and easily measurable exposures is massively inadequate. To mimic the methods by which private counterparties keep the other side’s opportunities for weaseling out of losses under control, capital requirements have begun to introduce small capital surcharges designed to increase both with an institution’s size and with the opacity of its deal making. But further reform legislation passed in 2018 benefits giant banks in two ways: by doing nothing new to rein in their ability to command safety-net subsidies when they are in distress and by expanding access to these subsidies for their custody activities. As always, an unreformed and elitist justice system continues to grant megabankers near-impunity for forcing the safety net—rather than their stockholders—to finance their firms’ deepest risk exposures.

Managers of temporarily well-capitalized banks are pressuring regulators to let them use dividends and stock repurchases to distribute as much of their current earnings as they can. Worse yet, regulators add their blessing to bankers’ bullsh*t claim that this is okay because low current levels of safety-net subsidies mean that safety-net subsidies are safely under control. While it is true that the value of safety-net guarantees is relatively low at U.S. megabanks today, this is because safety-net subsidies recede as a bank begins to build up its capital even a little. But the dialectical process I have outlined explains that, contrary to Adamanti and Hellwig (2013), increased capital requirements and incentive-conflicted stress tests cannot keep taxpayers’ loss exposure in megabanks under control for long. Whatever the level of capital requirements, the taxpayers’ stake increases when and as (notice I do not say if) bankers find new and better ways to hide leverage, tail risk and distress from their supervisors.

In principle, stress tests can compensate for some of the weaknesses in the design and implementation of capital requirements But in practice, stress tests focus narrowly on only a few very-specific scenarios. Because neither capital requirements nor stress tests measure taxpayer risks appropriately, stress tests merely add an overlay of bullsh*t to the perseverance of the citizenry’s hard-to-shake belief in the supervisory process. In any case, it looks as if regulators have stopped using these tests to assess the volatility of taxpayers’ stake in large banks. Beginning this year, the Fed appears to have repurposed the tests as a way to provide supervisory cover for captured regulators to permit the megabanks to use share buybacks and dividends to pay out enough of their accumulated profits to drive their safety-net subsidies up again.

Most commentators argue that U.S. megabanks are safer now that they were in 2007- 2008. But that is a superficial test. A more-important and unasked question is: For how long? Figure 1 tells us that the process of rebuilding megabanks’ leverage-driven tail risk by means of dividends and stock buybacks is already getting underway. Equally worrisome, bank information systems do not even try to track taxpayers’ stake in banking firms and the regulatory, supervisory and justice systems remain focused on disciplining banks, rather than bankers.

Figure 1: 2018 POST-CCAR SHAREHOLDER PAYOUTS FORECASTED FOR SELECTED US MEGABANKS AFTER STRESS TESTS

References

- Admati, Anat, and Martin Hellwig, 2013. The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong with Banking and What to Do About It. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Ferguson, Thomas and Robert Johnson, 2009. “Too Big to Bail: The ‘Paulson Put,’ Presidential Politics, and the Global Financial Meltdown,” Parts 1 and 2, International Journal of Political Economy, 38, nos. 1 (pp. 3-34) and 2 (pp. 5-45). Freely accessible pro tempore at http://explore.tandfonline.com/content/bes/the-2008-global-financial-crisis-looking-back

- Ferguson, Thomas, Paul Jorgenson, and Jie Chen, 2017. “Fifty Shades of Green: High Finance, Political Money, and the US Congress,” New York: Roosevelt Institute Working Paper (May). http://rooseveltinstitute.org/fifty-shades-green/